Key Takeaways:

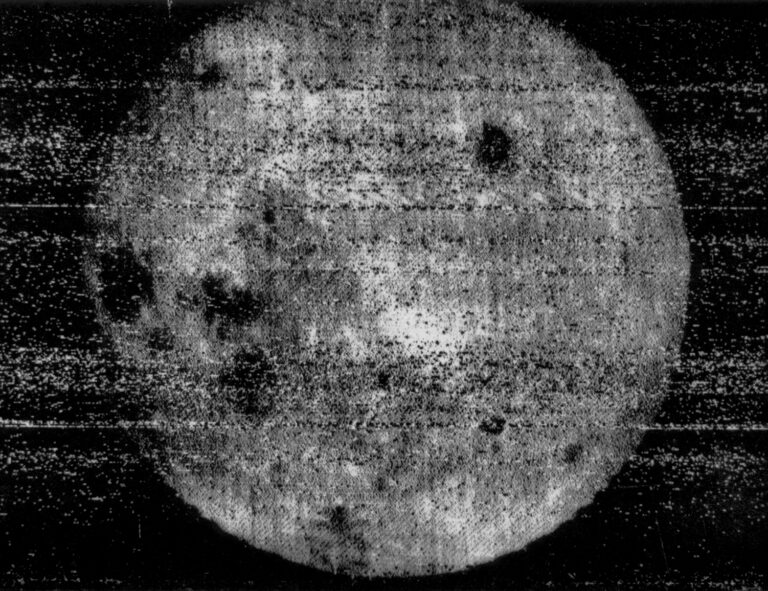

- Discrepancies in Uranus's orbital path, unexplained by Newtonian mechanics, hinted at the presence of an undiscovered planet.

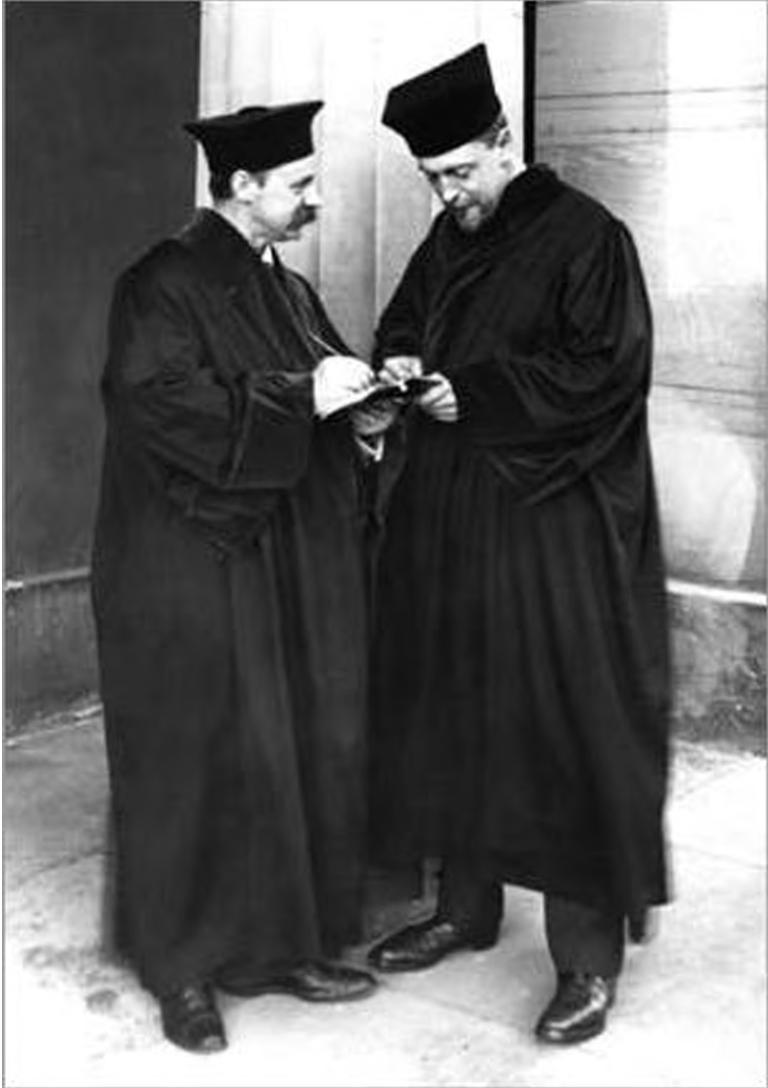

- Urbain Le Verrier and John Couch Adams independently calculated the potential location of this undiscovered planet through complex mathematical modeling of planetary motions.

- Johann Galle, using Le Verrier's calculations, successfully observed Neptune, confirming its existence and location within one degree of the prediction.

- While Le Verrier initially received primary credit, subsequent recognition acknowledged Adams's independent and equally accurate predictions, leading to shared credit for Neptune's discovery.

For decades following the discovery of Uranus in 1781, astronomers were puzzled by the irregularities in the planet’s orbit. Newton’s laws could not explain the perturbations observed, suggesting another planet was out there, affecting Uranus’ path. Two astronomers, Urbain Le Verrier in Paris and John Couch Adams in Cambridge, England, independently computed its likely location, a complicated process of reverse-engineering the motions of one planet from the motions of another. Le Verrier sent his calculations to the Berlin Observatory, where Johann Galle used them to successfully observe Neptune on Sept. 23, 1846. The newly discovered planet was only 1 degree away from where Le Verrier had predicted it would be, and was the first planet to be predicted by mathematical work. Unfortunately, a series of ignored communications and delayed analyses of observations meant that Adams’ predictions didn’t receive the same notice. Eventually, British nationalistic fervor brought attention to Adams’ calculations, which had also been quite accurate, and Le Verrier and Adams shared credit for the discovery going forward.