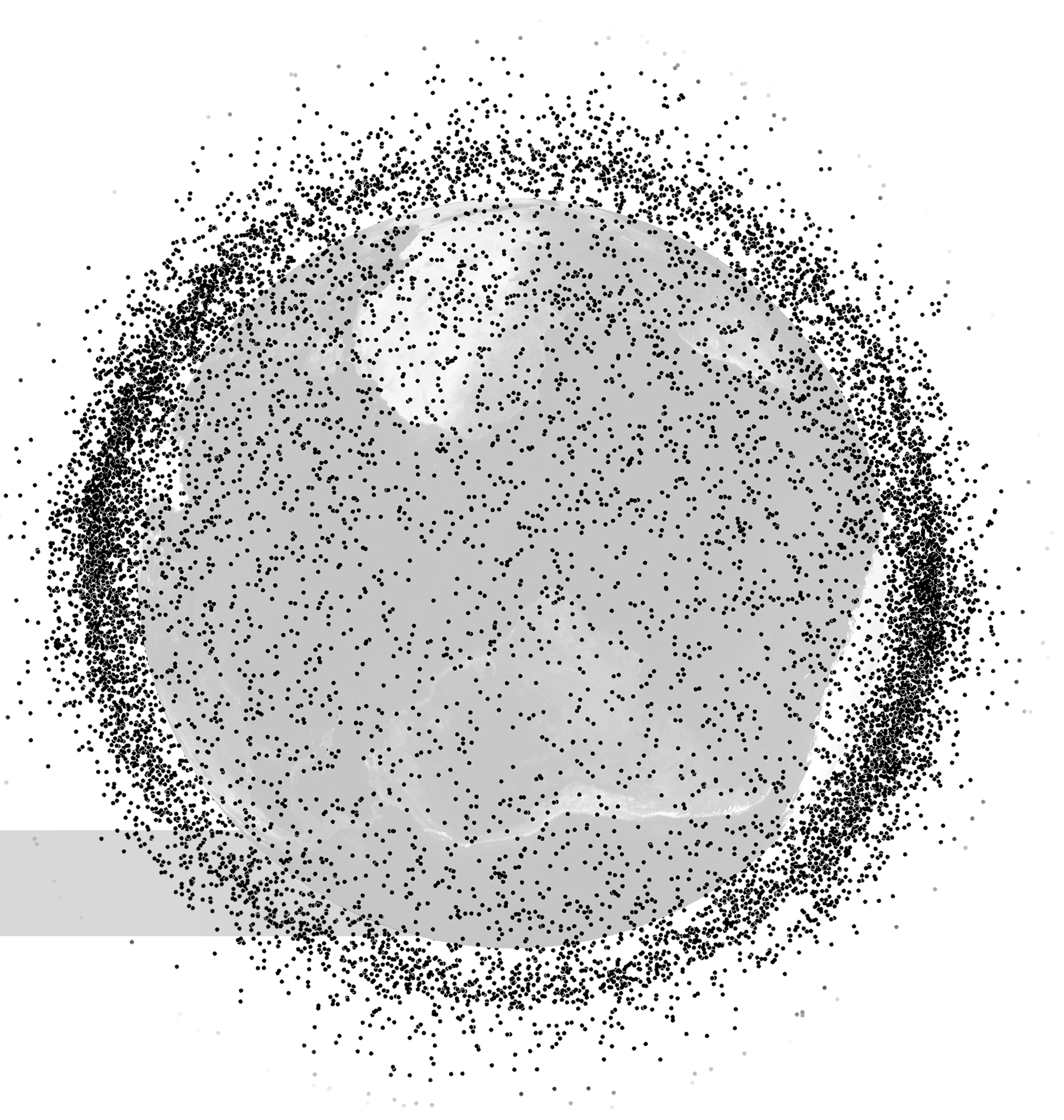

Credit: Pablo Carlos Budassi/WikiMedia Commons

Key Takeaways:

- The astronomical community faces a significant and escalating challenge due to the dramatic increase in satellite launches, transitioning from minimal interference by early constellations like Iridium to widespread contamination of data from current and future space telescopes.

- Projections indicate substantial image degradation for various space observatories; for example, Hubble is expected to have one-third of its images contaminated, while SPHEREx, ARRAKIHS, and Xiuntian could experience 96% or higher image ruin rates, with dozens of satellite trails per image.

- The visibility of most satellite trails during pre-sunrise and post-sunset periods forces telescopes to suspend imaging during these critical times, thereby impeding specific astronomical surveys, such as those for Earth-orbit-crossing asteroids, which necessitate twilight observations.

- In response, the International Astronomical Union Centre for the Protection of the Dark and Quiet Sky has proposed four key recommendations for satellite operators: limiting reflectivity, reducing bright flares caused by orientation changes, supporting an observing network for light contamination, and publicly sharing satellite reflectance test data.

A new report in Nature discusses how the dramatic increase in satellite launches will affect astronomy.

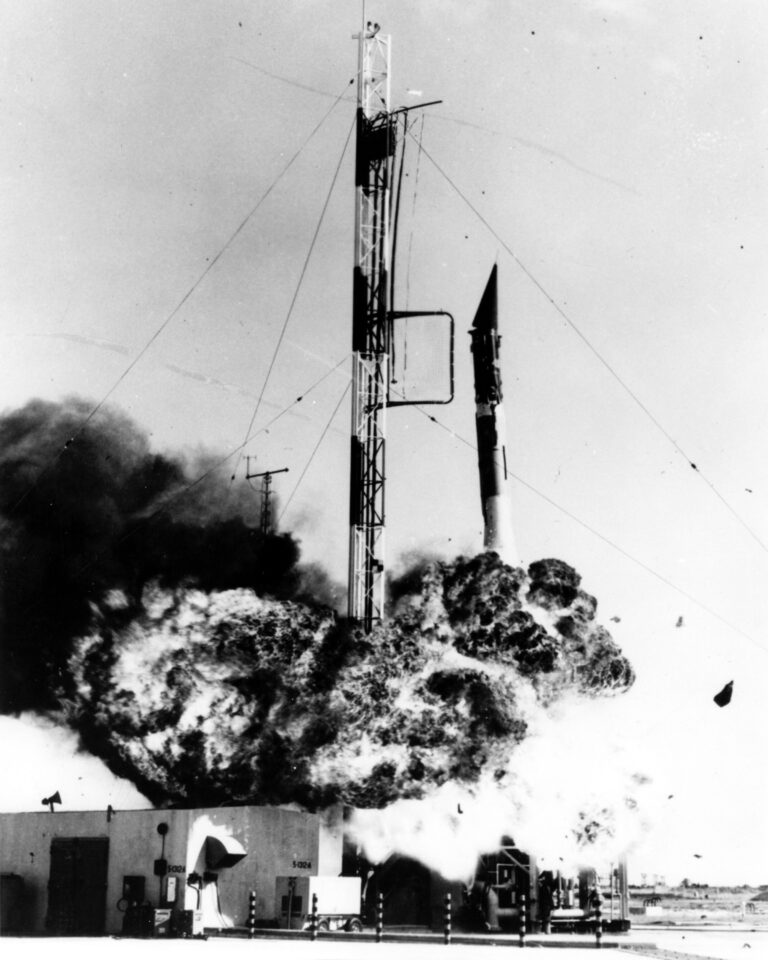

Before 2019, the largest group of associated satellites was the Iridium satellite constellation, which first launched five satellites on May 5, 1997. Currently, 76 are active with six spares also in orbit. I remember our astronomy club in El Paso going out during evening twilight to watch “Iridium flares,” which were bright reflections off the panels of individual satellites. Back then, we thought they were fun to watch. But we weren’t collecting data that such flares interfered with.

The Iridium constellation was placed into low-Earth orbit, which is usually defined as lying between 390 and 485 miles (630 and 780 kilometers) above our planet. The first space observatory impacted by this was the Hubble Space Telescope, which now operates at an altitude of 334 miles (538 km). That meant the Iridium satellites were between Hubble and its celestial targets. But because there were so few of them, their impact was small and astronomers paid them almost no mind.

The future looks bright — unfortunately

Things are different now. Currently, more than 15,000 satellites orbit our planet, and if predictions are correct, by the end of the 2030s that number will grow to half a million thanks to next-generation superlaunchers (rockets with heavier payload capacities).

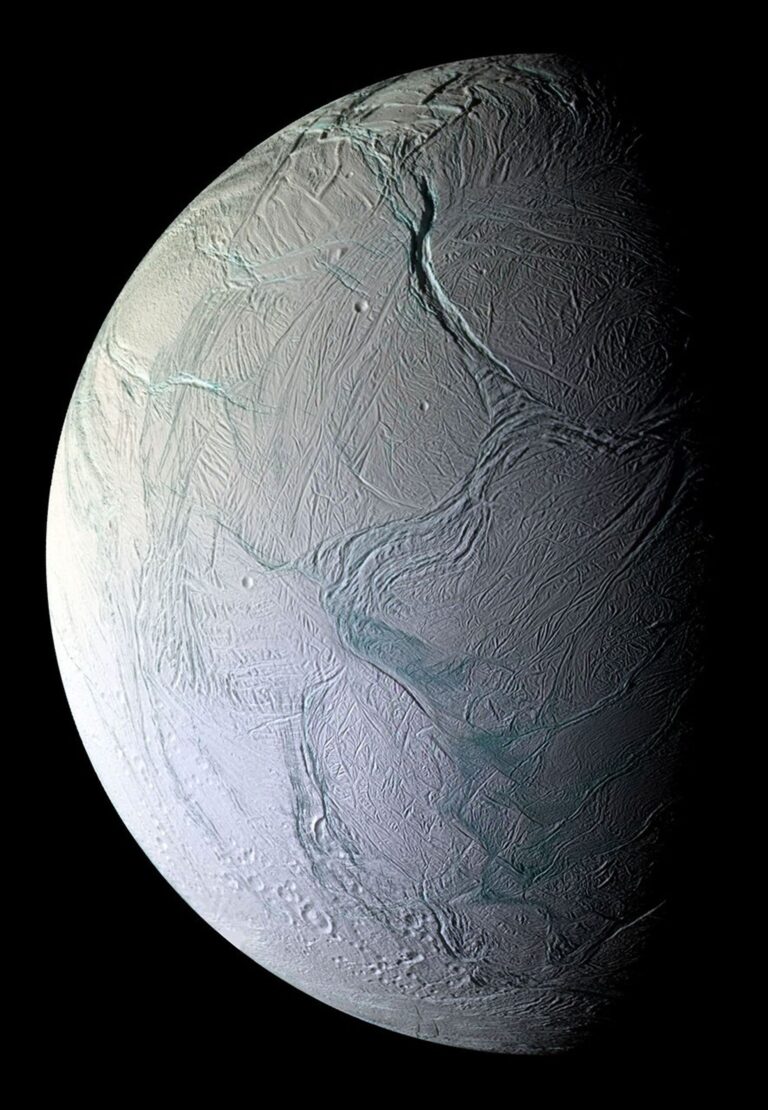

If these predictions come to pass, one-third of the images Hubble produces will be contaminated by satellite trails —bright streaks across the image — rendering the data unusable. But Hubble is just the beginning. NASA’s recently launched SPHEREx near-infrared observatory, which orbits at an altitude of 430 miles (700 km), will have 96 percent of its images ruined by an average of 5.6 satellite trails on each image.

A similar percentage of images will be ruined for the European Space Agency’s ARRAKIHS visual and near-infrared space telescope, due to launch to an altitude of 500 miles (800 km) in 2030. Although, by then an average of nearly 70 satellite trails will cross each image. And images from next year’s planned launch of China’s Xiuntian space telescope, which will orbit roughly 250 miles (400 km) high, will contain an average of 92 satellite trails on each image.

Solutions?

Because most satellite trails become visible before sunrise and after sunset, telescopes have been shutting down their imaging during those times. But some surveys, like those searching for unknown Earth-orbit-crossing asteroids, can be done only during those times.

In February 2024, the International Astronomical Union Centre for the Protection of the Dark and Quiet Sky suggested four recommendations for satellite operators and manufacturers to minimize the impact of satellite constellations. The first was to limit the reflectivity of satellites. The second was to try to reduce the number of bright flares that are caused when a satellite changes its orientation. Third was to support an observing network that will report on light contamination from satellites. And fourth was to perform reflectance tests on the satellites’ surfaces and make that data available to the astronomical community.

Hopefully, science and industry can come together to solve this serious and escalating problem.