The world lost a true hero Aug. 7, when astronaut and space pioneer Jim Lovell passed away at age 97. The first person to fly in space four times, Lovell helped pave the way for the first Moon landing and came to epitomize NASA’s can-do attitude.

I had the honor and pleasure to interview Lovell three times during the latter half of the 2010s. Always gracious, humorous, and engaging, he became a good — dare I say it — friend. What follows is a remembrance, sprinkled with his reflections culled from our interviews.

Related: Jim Lovell in his own words

The early years

James Arthur Lovell Jr. was born in Cleveland on March 25, 1928. After his father died in a car accident in 1933, he and his mother moved to Terre Haute, Indiana, where they lived with a relative for two years. Lovell spent his formative years in Milwaukee. He excelled in school and became an Eagle Scout, yet still found time to study rocketry and build model rockets.

Finances were tight in the Lovell household, and Jim had few options to continue his education after high school. Enter the U.S. Navy. Although the prestigious and selective Naval Academy rejected Lovell’s application, the service had just initiated a program that provided two years of free college tuition to study engineering. Flight training and a year of active duty followed. The students were then allowed to complete their degrees before becoming naval aviators.

Lovell completed his two years at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, but then reapplied to the Naval Academy at the urging of his mother, who feared that an outbreak of war could unduly delay his education. The second time proved to be the charm. He graduated in 1952 and soon started flight training in Pensacola, Florida. Fourteen months later, he officially became a naval aviator and began flying night missions off aircraft carriers in the Pacific.

Gemini astronaut

Although Lovell was happy as a carrier pilot and later instructor, by 1957 that career had lost some of its excitement. He applied for a transfer to the Naval Air Station in Patuxent River, Maryland, where he planned to test experimental aircraft. But the ground beneath aviation was shaken to its core Oct. 4, 1957, when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik into Earth orbit. Suddenly, the horizon aviators could envision stretched far beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

Lovell set his sights on becoming an astronaut, and in 1958 he was one of 110 test pilots selected as candidates for the Mercury program. Like his initial rejection from the Naval Academy, he didn’t make the cut. A high count of a liver compound meant he wouldn’t be one of the Mercury Seven, the group who would make America’s first forays into space.

Of course, seven astronauts wouldn’t be able to crew all of the planned two-man Gemini and three-man Apollo flights. NASA started recruiting a second astronaut group in 1962 and, this time, Lovell made it. He joined eight other winners in the so-called “Next Nine” or “New Nine,” a veritable who’s who of astronauts destined to achieve President Kennedy’s goal of “landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth.”

The Gemini program was designed to test every procedure needed to realize Kennedy’s objective. Ten crewed flights in 20 months demonstrated astronauts’ abilities to rendezvous and dock two spacecraft; start, stop, and restart rocket engines; function productively outside a spacecraft; and, most importantly, live in space for an extended period.

Lovell’s two Gemini flights played critical roles in achieving these milestones. In December 1965, Gemini VII — NASA was as fond of using Roman numerals for the Gemini flights as the NFL is in numbering Super Bowls — sent Lovell and Frank Borman into Earth orbit for 14 days, longer than any of the Apollo Moon missions. The two astronauts also participated in the first rendezvous with another crewed mission when they met Gemini VI-A and flew in tandem with the other ship for three orbits.

The final mission in the program, Gemini XII, came in November 1966. Lovell teamed with Buzz Aldrin on this four-day flight that proved humans could work outside the spacecraft. Although four NASA astronauts — Ed White, Gene Cernan, Michael Collins, and Dick Gordon — previously had performed spacewalks, none went particularly well. But Aldrin equipped himself with special tethers, foot restraints, and portable handholds, buzzing around the space capsule as if on a walk in the park.

To the Moon

Lovell would not fly again for two years. The tragic launchpad fire that killed the Apollo 1 crew — Gus Grissom, White, and Roger Chaffee — on Jan. 27, 1967, forced NASA to delay the program while the agency figured out what went wrong and then redesigned the spacecraft’s command module. Flights resumed with Apollo 7 in October 1968. Lovell would get his next opportunity two months later on Apollo 8.

The historic mission to the Moon hadn’t been planned that way. NASA originally conceived Apollo 8 as a test flight for the lunar module in low Earth orbit, following on Apollo 7’s successful test of the command and service modules. But the lunar module program was running behind schedule and wasn’t ready for Apollo 8. NASA made the bold move to swap the crews of Apollos 8 and 9, and fly 8 to the Moon. “I guess there’s a certain amount of luck in everybody’s life,” said Lovell, who joined Gemini VII crewmate Borman and rookie astronaut Bill Anders on the Apollo 8 crew.

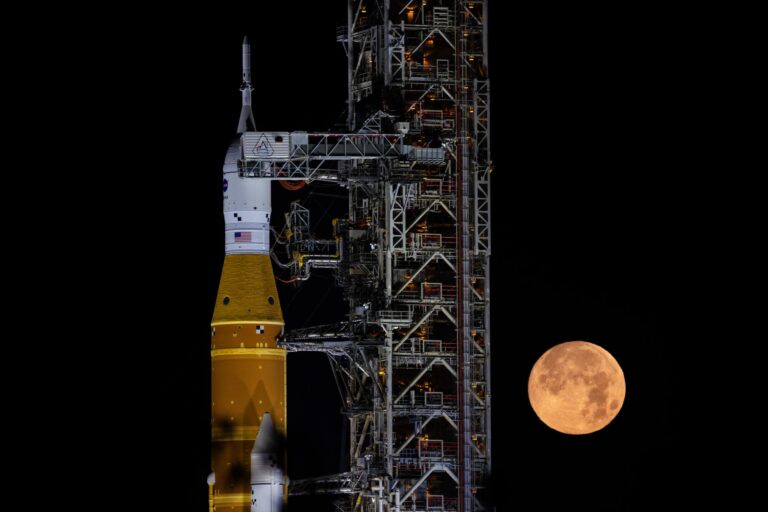

Assassinations, riots, and an unpopular war had dominated the news in 1968. But these three men were about to change the year’s grim narrative. On the morning of Dec. 21, Apollo 8 lifted off from Florida’s Kennedy Space Center on top of the powerful Saturn V rocket. A few hours later, the crew became the first humans to slip the bonds of Earth’s gravity when they lit the Saturn V’s third stage.

Three days later, Apollo 8 fired its service module engine and entered the first of its 10 lunar orbits. Lovell told me his most profound memory of the lunar visit was his new perspective on Earth: “When I looked out at the Earth for the first time, 240,000 miles away, my world suddenly expanded to infinity. I could put my thumb up to the window and completely hide the Earth. And I suddenly realized that behind my thumb, on this little planet, was about 5 billion people. Everything I ever knew was behind my thumb.”

Lunar orbit also brought the astronauts’ iconic reading of the first 10 verses from Genesis. And it gave Lovell his first close-up look at Mount Marilyn. He had spotted this triangular-shaped peak during training and thought it might make a good reference point for the Apollo 11 astronauts who would land on the adjacent Sea of Tranquillity. He unofficially named it after his wife, Marilyn Lillie Lovell, who would remain married to Jim for 71 years until her death in 2023.

In a mission filled with firsts, perhaps the most memorable is a single image called “Earthrise.” It showed a stark lunar landscape with a beautiful blue planet hanging in the blackness of space, capturing the fragility and isolation of our home planet. Although Anders was the mission photographer, Lovell was quick to point out the alignment to him. “When the Earth drifted over to my window and I looked at it and saw the composition of the Earth with respect to the lunar horizon, I said, ‘Bill, this is it. This is the picture.’ ”

Houston, we’ve had a problem

With the successful landings of Apollos 11 and 12, spaceflight had become routine, if not a little boring, for many Americans. Apollo 13 would change that in an instant. Once again, fate played a role. Lovell was initially scheduled to go back to the Moon on Apollo 14, but NASA decided that 13’s slated commander, Alan Shepard, didn’t have enough training and swapped crews.

Lovell and rookie crewmates Jack Swigert and Fred Haise lifted off April 11, 1970, for what was supposed to be the first lunar mission to concentrate on science. Although not a superstitious guy who believed the number 13 was unlucky, Lovell told me, “As you look at the flight and you analyze the mission from its inception to the finish, you’ll see that it was plagued by bad omens and bad luck.”

Jack Swigert only made the crew because original member Ken Mattingly had been exposed to the German measles, and he was the only crew member not immune from prior exposure. In addition, one of the ship’s oxygen tanks had been damaged earlier and, though apparently repaired, was still behaving oddly. Then, less than six minutes into the flight, one of the engines shut down two minutes prematurely. The other engines managed to compensate, however, and all seemed well as the crew headed toward the Moon.

That changed two days later, on April 13. Some 200,000 miles from Earth, the damaged oxygen tank exploded during a routine stirring. It caused the other tank to fail, and cascading events left the command module without its supply of electricity, light, and water. Most people would have panicked. But Lovell and his crewmates were former test pilots, and they knew how to handle adversity.

Along with mission control, they figured out solutions. First, they would use the lunar module as a lifeboat to get back. Second, they had to alter the spacecraft’s course, which was designed to get them into lunar orbit, to get on a free-return trajectory. Then, they had to speed up to get back to Earth before their supplies ran out.

Maneuvering proved to be a big problem. NASA didn’t design the lunar module to fly while attached to the command and service modules. Yet they couldn’t jettison the command module because they needed its heat shield to protect them during reentry. “The center of gravity, instead of being in the center of the lunar module like it is normally, was way out in left field someplace,” said Lovell. “So, I literally had to learn by the [way it handled] how to maneuver. Fortunately, when you’re in deep trouble, you learn pretty fast.”

The other major problem was the buildup of carbon dioxide. “The lithium-hydroxide canisters [on the lunar module] were designed to remove carbon dioxide from two people for two days, and we were three people for four days,” said Lovell. “It meant that we had to take a square canister from the command module and rig it into the environmental system of the lunar module, which used round canisters that went into round holes. We ended up using duct tape, plastic, a piece of cardboard, and an old sock to jury-rig [a] system to remove the carbon dioxide.”

The crew made it safely back to Earth on April 17. They received a hero’s welcome, a far cry from the ho-hum reaction to their liftoff.

Jim Lovell gave hundreds of interviews over the years, and I was privileged to conduct three of them. His warmth, insight, and down-to-Earth humor came through in every response. I consider my time with him a highlight of my 40-year career at Astronomy.

On July 26, 2017, nearly 50 years after Lovell’s Apollo flights, the International Astronomical Union recognized Mount Marilyn as the official name for that peak on the Sea of Tranquillity’s edge. As he told me in 2018, “From that day on, in perpetuity, looking down at me long after I’m gone, will be this little triangular mountain named Mount Marilyn.” May our memory of Jim Lovell and his fellow space pioneers survive as long.