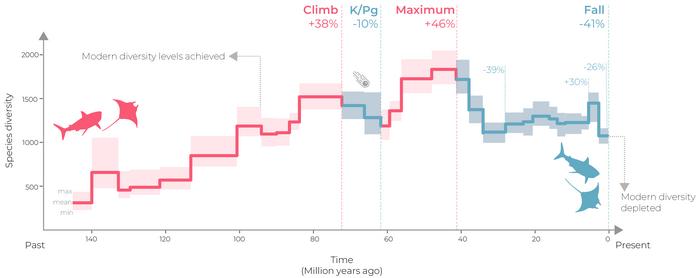

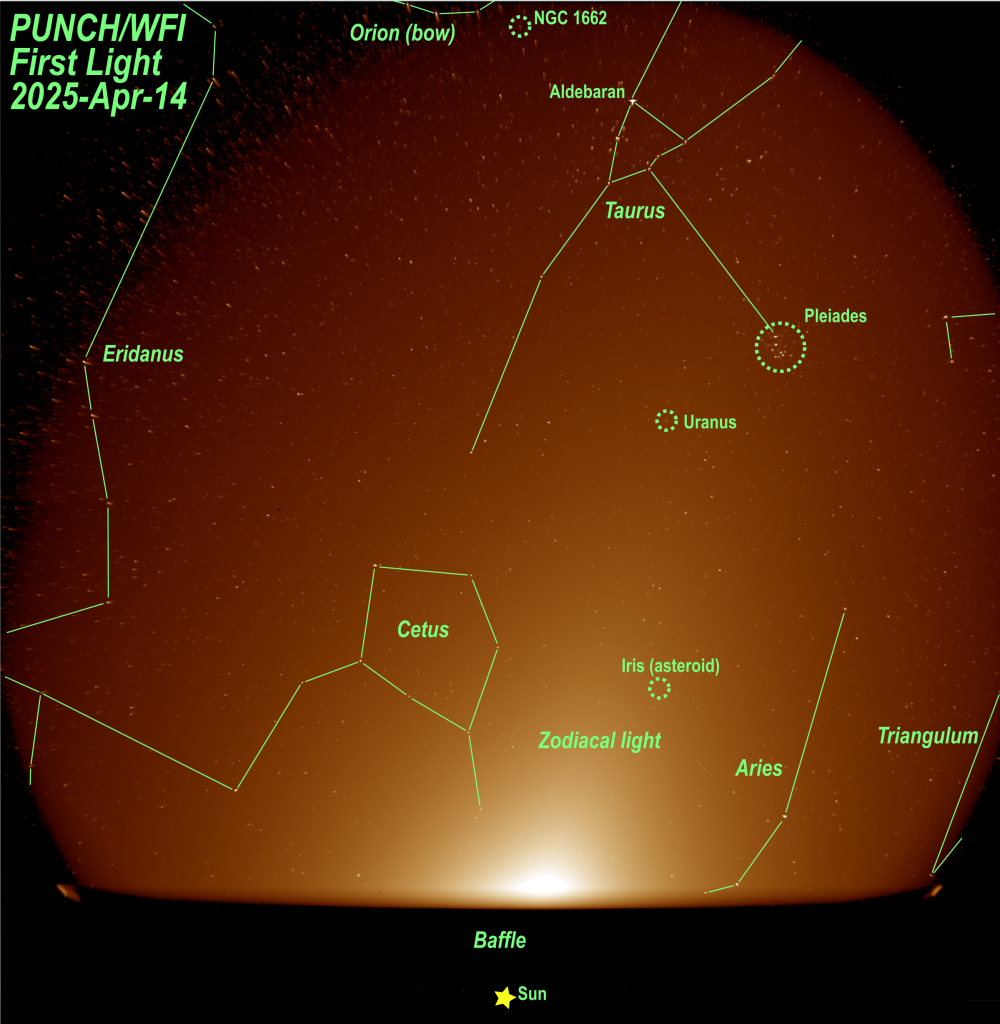

NASA’s Polarimeter to Unify the Corona and Heliosphere (PUNCH) mission launched March 12, sending up a constellation of four Earth-orbiting satellites with the goal of studying how the Sun’s activity influences the space environment around Earth. This week, the four satellites opened their cameras to the sky and captured their so-called first light images in a major milestone for the mission. The successful snapshots show that the cameras are both in focus and working as expected, allowing the mission to move forward.

Related: NASA’s PUNCH will study how the Sun influences the space around us

The parts of PUNCH

PUNCH consists of three identical satellites each carrying a wide-field imager (WFI) and one satellite equipped with a narrow-field imager (NFI) coronagraph. The WFIs’ broad view allows astronomers to study the solar wind that extends far into space beyond the Sun. Meanwhile, the NFI homes in on the Sun’s more immediate surroundings, blotting out the light from the bright disk to image a doughnut-shaped region just beyond the surface. This unique view lets astronomers peek at our star’s strange, superheated corona, or outer atmosphere. The four simultaneous views can be virtually combined into one final image to allow astronomers to study small- and large-scare phenomena all at once, in particular to learn how changes in the corona affect the solar wind that streams throughout the solar system toward Earth.

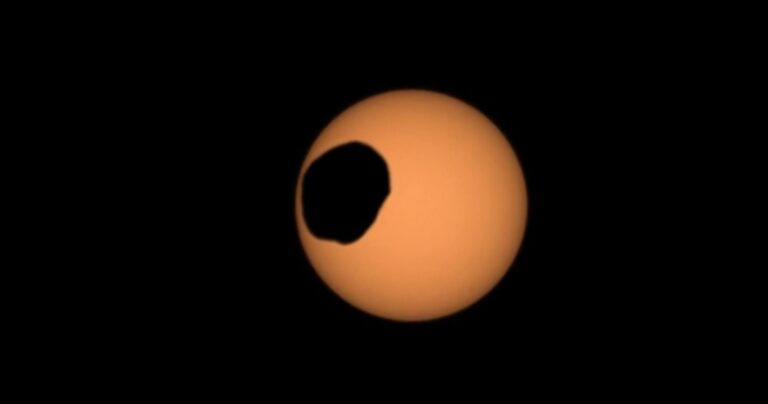

NFI first light

The NFI opened its eye to the sky first on April 14, imaging the Sun against the background stars of the constellation Pisces. The view here has been specifically filtered to bring out those background stars, which are otherwise blotted out by the bright zodiacal light generated by sunlight glinting off dust particles in the inner solar system. Also visible is a sliver of the Sun’s corona at center, reminiscent of the view during an annular solar eclipse.

You might notice several strange, streaky crescent-shaped artifacts at right. These arise from a small misalignment between the imager and the Sun, allowing stray sunlight to glint off the optics where it’s not quite blocked by the coronagraph. Engineers will use this and subsequent images to adjust the NFI’s position on the sky to bring it in full alignment with our star and eliminate stray light in future scientific data. Ultimately, that calibration will allow just one percent of the corona’s light through to the imager, providing clear views of faint structures and changes within the corona as the Sun spews material out into space.

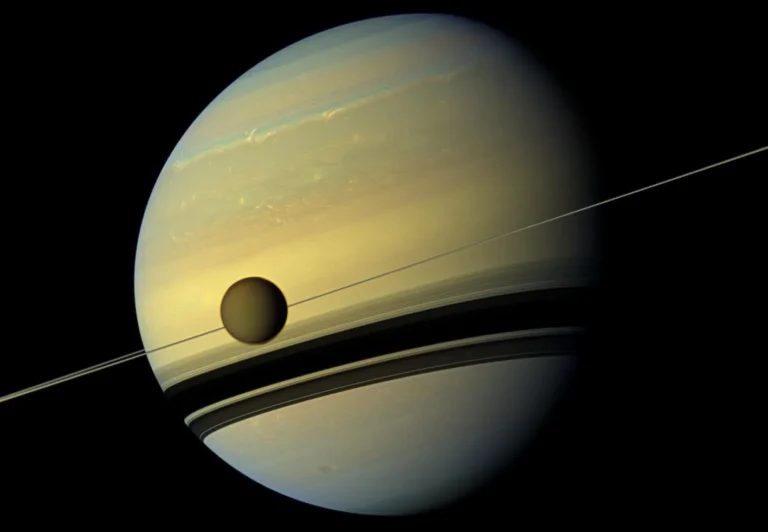

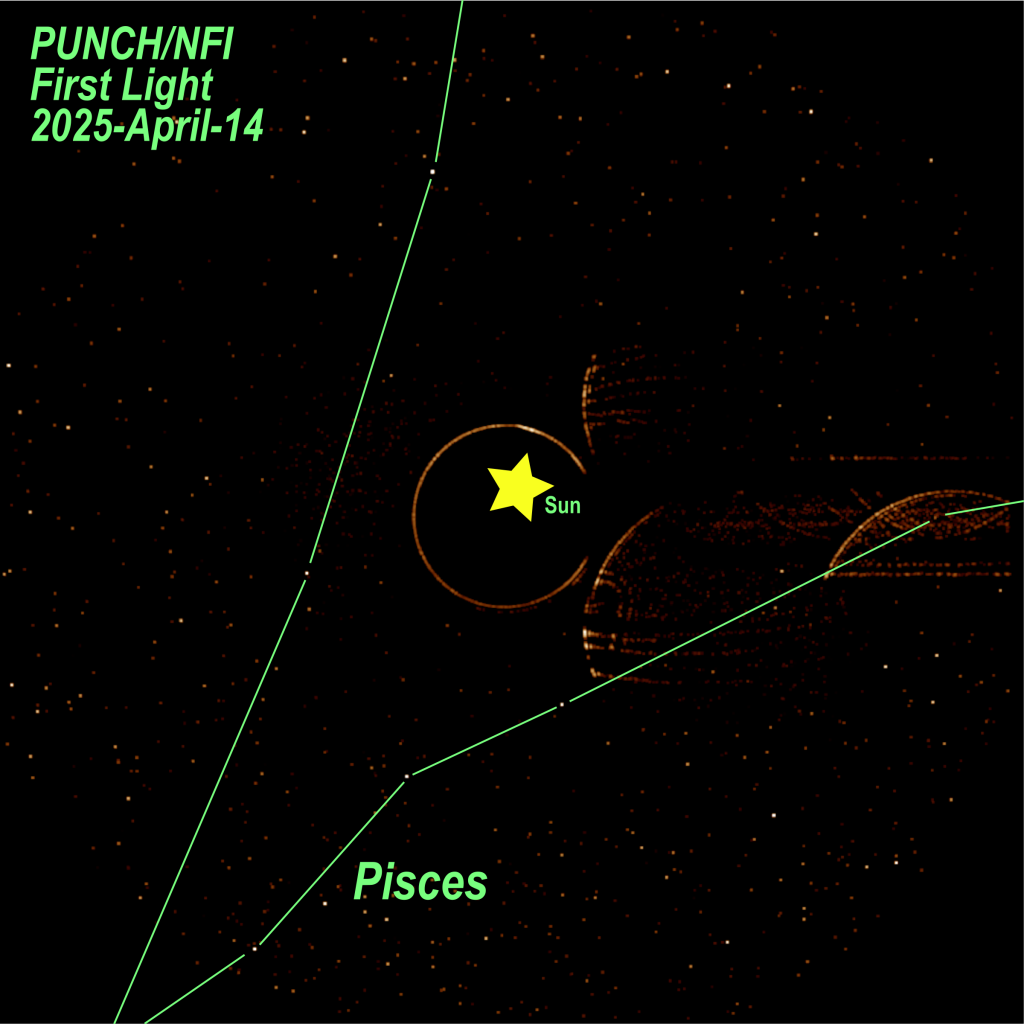

WFI first light

Two days later, on April 16, the three WFIs got their first look at the Sun, taking in a broad view across the solar system. These instruments are designed to look at the region of space out to some 45° from the Sun’s position, roughly out to the distance of Earth’s orbit projected on the sky. Their fields of view don’t overlap, but instead form a trefoil pattern that rotates over time.

That immense field of view is evident in the WFI first light image, which marks the position of the Sun at bottom (intentionally outside the field) and outlines several constellations and other objects for reference, including the asteroid 7 Iris photobombing the shot at lower right. Prominent across the entire image is the intense glow of the zodiacal light.

Science soon

It’s worth noting that these first light images look very different from the way PUNCH’s science observations will appear. Although these shots show numerous stars and the bright zodiacal glow, scientists will remove all this background light from the final images. This is so PUNCH can show clearly detailed structure within Sun’s corona and solar wind, which can be quite faint. Additionally, PUNCH will be the first mission to show these features in polarized light, which reveals how the electric fields of the light waves are aligned and will provide never-before-seen clues about how the Sun’s wind behaves and evolves over time.

PUNCH’s commissioning phase is expected to last 90 days, after which the group of four satellites will commence its two-year science mission.