Credit: Nandal et al

For two decades, astronomers have wondered how supermassive black holes could exist less than a billion years after the Big Bang. They knew that the processes inside normal stars simply couldn’t create such objects within that time frame.

But if so-called “monster stars,” those with masses between 1,000 and 10,000 times that of our Sun existed, that would solve the mystery. Recently, an international team of scientists using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has found the first compelling evidence for such objects.

Galactic chemistry

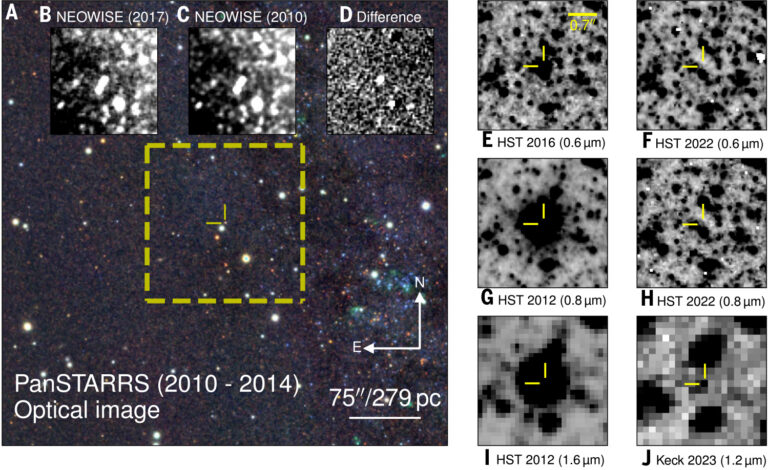

The breakthrough came when researchers looked at the spectrum of a galaxy called GS 3073, which lies in the southern constellation Fornax the Furnace at a distance of approximately 12 billion light-years. The study, led by the University of Portsmouth in England and the Center for Astrophysics (CfA), Harvard and Smithsonian in the U.S., discovered an extreme imbalance of nitrogen to oxygen that cannot be explained by any known type of star.

In 2022, researchers published work in Nature predicting that supermassive stars in the early universe form in turbulent streams of cold gas. This explained how quasars (extraordinarily bright objects powered by black holes) could exist less than a billion years after the Big Bang.

“Our latest discovery helps solve a 20-year cosmic mystery,” said Daniel Whalen from the University of Portsmouth’s Institute of Cosmology and Gravitation. “With GS 3073, we have the first observational evidence that these monster stars existed.

“These cosmic giants would have burned brilliantly for a brief time before collapsing into massive black holes, leaving behind the chemical signatures we can detect billions of years later. A bit like dinosaurs on Earth — they were enormous and primitive. And they had short lives, living for just a quarter of a million years — a cosmic blink of an eye.”

The key to the discovery was the ratio of nitrogen to oxygen in GS 3073 — an amazing 0.46. This fraction is a lot morethan any known star or stellar explosion can produce.

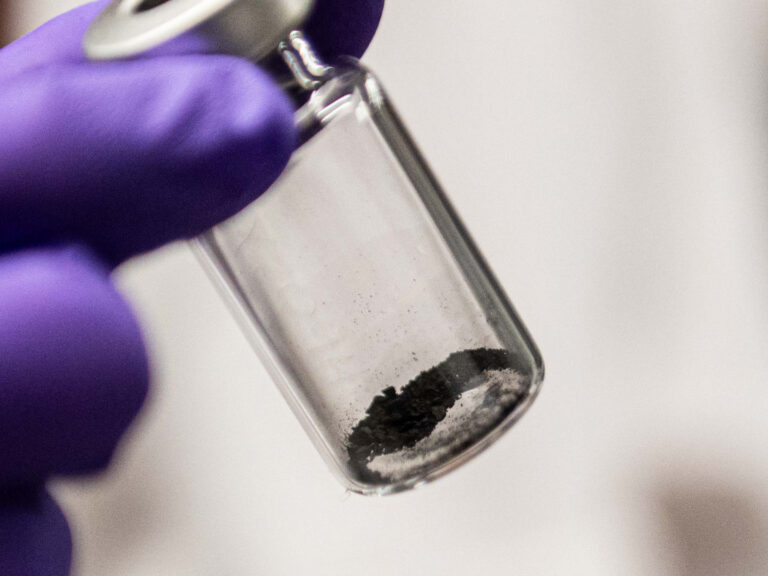

Devesh Nandal from the CfA’s Institute for Theory and Computation explained: “Chemical abundances act like a cosmic fingerprint, and the pattern in GS 3073 is unlike anything ordinary stars can produce. Its extreme nitrogen matches only one kind of source we know of — primordial stars thousands of times more massive than our Sun. This tells us the first generation of stars included truly supermassive objects that helped shape the early galaxies and may have seeded today’s supermassive black holes.”

Evolution

The team performed computer modeling on stars between 1,000 and 10,000 solar masses. They wanted to know how they would evolve and what elements they would produce. They theorized a process that would create such massive amounts of nitrogen.

First, such huge stars would begin fusing helium into carbon in their high-temperature cores. That carbon would eventually leak into a shell of hydrogen surrounding the core. There the carbon would fuse with hydrogen in a well-known process called the carbon-nitrogen-oxygen (CNO) cycle. That fusion would produce nitrogen. Convection currents, which all stars have, would then distribute the nitrogen throughout the star. Finally, the star sheds the nitrogen, which enriches the surrounding interstellar medium, and in this case, the galaxy.

The study also found that the nitrogen abundance only appears in stars smaller than 1,000 solar masses or larger than 10,000 solar masses. Those outside this range don’t produce the right chemistry.

The process would remain active during the time the star is fusing helium. That phase lasts a few million years, but it’s long enough to create the nitrogen excess observed in GS 3073.

The models, published in Astrophysical Journal Letters, also predict what happens when these monster stars die. They don’t explode, instead, they collapse directly into massive black holes weighing thousands of solar masses.

More discoveries await

GS 3073 also contains an actively feeding black hole at its center. If this is the remnant of one of the supermassive first stars, it would solve two mysteries at once — where the nitrogen came from and how the black hole formed.

This research gives us another look into the universe’s first few hundred million years — a period astronomers call the “cosmic Dark Ages.” This is when the first stars ignited, later transforming the simple chemistry of the early universe into the rich variety of elements we see today.

The researchers predict that JWST will find more galaxies with similar nitrogen excesses. Each new discovery would strengthen the case for these ultra-massive first stars.