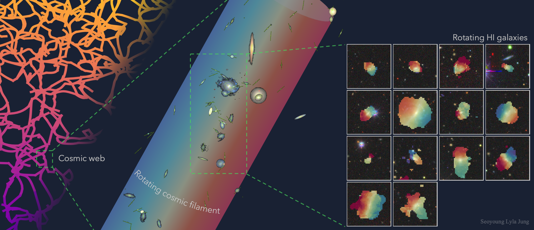

Credit: Lyla Jung

Approximately 424 million light-years away, a vast chunk of the cosmic web (the network-like distribution of matter the universe displays on the largest scale) appears as if it’s been caught in a vortex. It’s the biggest single spinning structure astronomers have ever seen, measuring around 117,000 light-years across and 5.5 million light-years long. The discovery also contains clues about how early galaxies formed.

Scientists found it in survey data from South Africa’s MeerKAT radio telescope. Additional observations by the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) and Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) revealed more details.

First, they detected members on one end of a string of 14 galaxies moving toward us and ones on the other end moving away. That suggests they’re all turning together, moving at a leisurely (astronomically speaking) 250,000 miles per hour.

Intrigued by this strange synchrony, astronomers took a closer look and found that the strand of the cosmic web the galaxies are embedded in is also twisting along with them.

Similar, but different

That’s been known to happen before. Gas in the cosmic web swirls in eddies here and there as it flows along unevenly distributed matter, like water encountering a rock in a stream. But the galaxies are each spinning too, and most of them happen to be rotating in the same direction as the filament; very odd considering astronomers generally think the direction galaxies spin is random. At least in this case, it seems the two may be linked, which could help us figure out how galaxies pick up their angular momentum in the first place.

“We believe this [alignment] is caused by the gravitational interaction between the galaxies and the filaments,” said Madalina Tudorache, a postdoctoral research assistant at the University of Oxford who led the study. “More specifically, there is a transfer of angular momentum from such a large-scale to the galaxies. This is very important as we are trying to paint a better picture of galaxy formation and evolution in the context of their environment.”

The galaxies in this structure are brimming with neutral hydrogen, the raw material for star formation. Because hydrogen is so easily disturbed, it acts like a motion detector, showing how gas and momentum flow through the cosmic web. That makes this filament a kind of live demo of how galaxies gather the material and spin they need to grow.

On the lookout for more

Finding more such structures could fill in additional pieces in the puzzle of galaxy growth. “Statistically, we believe there are other spinning structures, some of which could be larger –– however, we have not been able to detect them directly with our current data and telescopes,” Tudorache said. “With the new data coming both from radio telescopes (for the atomic neutral hydrogen from MeerKAT) and from optical telescopes such as Vera Rubin and Euclid, we are planning to look for more of these structures to hopefully be able to describe them more accurately as a population.”

Scientists hope to understand them as well as possible because they could contaminate weak lensing observations, which enable astronomers to study the distribution of dark matter and the universe’s accelerated expansion. These observations are possible because light’s path bends as it travels through the warped space-time around matter it passes on its journey across vast distances.

Weak lensing has a faint funhouse mirror effect that makes background galaxies appear to be aligned. So if galaxies are aligned for a different reason (like being synced up with their filament), that could be mistaken for a weak lensing signal, making that data less precise.

“The alignment between galaxies within filaments (or other cosmic structures) breaks our assumption that without gravitational lensing all galaxies are randomly orientated,” said Naomi Robertson, a postdoctoral research associate at The University of Edinburgh, who was not involved in the study. “So we need to account for this effect when we make predictions for what our lensing measurements should look like. Now what’s interesting in this work is that they are finding more alignment than the simulations predict.”

Cosmological probes

Robertson says working with observations like this gives astronomers a chance to test out how they analyze this data so they’ll be better prepared to handle Rubin and Euclid data. “Alignments inside filaments aren’t just a contaminant to weak lensing observations, filaments are really interesting cosmological probes in their own right,” she adds, “as it is predicted that over 40 percent of the mass of the universe is in filaments. The combination of overlapping weak lensing, spectroscopic and HI [neutral hydrogen] surveys provides complementary datasets which we can use to fully explore the cosmic web.”