“Of all the heavenly bodies, comets are assuredly those whose appearance strikes most forcibly the attention of mortals,” wrote French astronomer Camille Flammarion in his book Popular Astronomy (1894). And, for as long as humans have looked toward the sky, it’s been true. Comets have both terrified and amazed us.

This was never more apparent in modernity than in 1910. Comet 1P/Halley, better known as Halley’s Comet, had last been visible in 1836 and would grace the heavens again that spring. The comet’s return was highly anticipated, so imagine everyone’s surprise when a brilliant comet unexpectedly appeared months earlier.

The object that would become known as both the Great January Comet of 1910 and the Daylight Comet was first seen Jan. 12 in the Southern Hemisphere. It’s unclear who precisely discovered it, but some newspapers at the time pointed to observers in South Africa. On Jan. 17, the comet reached perihelion — its closest approach to the Sun — and could be seen in broad daylight, outshining Venus at its brightest. As it moved away from the Sun, it became visible in the Northern Hemisphere shortly after sunset. By February, a 50°-long tail swept away from the comet’s head.

Confusion caused many to mistake the apparition for the more famous Halley’s Comet, which was seeing increased media attention after scientists detected the presence of cyanogen in its tail. With Earth predicted to pass through it on May 18/19, Flammarion warned in The San Francisco Call Feb. 8, 1910, that the gas could “impregnate the atmosphere and possibly snuff out all life on the planet.” The misinformation ran counter to the scientific consensus that any danger would be eliminated when the cyanogen decomposed in the upper atmosphere.

By early April 1910, when Halley’s Comet became visible once more, a full-blown media extravaganza surrounded its return. At this point, some thought Halley would collide with Earth, despite astronomers’ assurances to the contrary. As panic ensued, charlatans hawked comet pills as protection against the deadly gas, while others flocked to churches, bought gas masks, and tried to seal up their homes to keep out the cyanogen.

Despite the efforts of astronomers and scientists, humanity’s latent fear of these celestial visitors had resurfaced.

Ruining perfection

Many ancient cultures saw comets as harbingers of doom and disaster. The predictable motions of the planets, the Sun, and the Moon, as well as the seasonally changing constellations, were reassuring in a chaotic world. A comet’s sudden appearance shattered this order.

Aristotle described Earth and the sky as fundamentally different spheres. The terrestrial sphere was ever-changing and corruptible. Beyond lay the realm of perfection where the Sun, the Moon, and planets rotated on incorruptible crystalline spheres. It seemed inconceivable that a random disruption could pass through this realm of perfection. So, to explain this corruption, Aristotle suggested that comets were vapors that rose from Earth and ignited in the upper atmosphere. Astronomers ultimately rejected Aristotle’s explanation, but his views held sway in Western philosophy for more than 1,500 years.

Westerners weren’t alone in these beliefs, either. Chinese astronomers called comets “bushy stars” (bèi xīng) if they had no tail, or “broom stars” (huìxīng) if they had one. Ancient Chinese records of comet observations were the most extensive and accurate of both the ancient and medieval periods. Yet they too saw these visitors as disastrous omens.

Signs and Omens

Comets were viewed as disruptors of a perfect cosmic routine. As Carl Sagan said, a comet’s appearance was “assured of some tragedy for which it can be held accountable.” Halley’s Comet made an easy scapegoat over the centuries, each time it returned to the sky.

1066: The cosmic visitor was viewed as a bad omen for the Anglo-Saxons’ kingdom, then ruled by Harold II. A month after William of Normandy invaded, the king died at the Battle of Hastings. The Bayeux Tapestry, which recorded the conquest, depicts the first-known illustration of Halley’s Comet.

1301: Halley’s Comet once again graced the heavens. A few years later, Italian artist Giotto di Bondone painted The Adoration of the Magi. Art historians believe this was Comet Halley as Giotto remembered it — a rare example of Halley’s comet being viewed as a blessing.

1456: The last vestige of the Roman Empire vanished when the Ottomans captured Constantinople in 1453. Europe was awaiting a full-scale invasion from the Turkish army when Comet Halley reappeared in 1456, fueling panic and despair. By some reports, Pope Calixtus III ordered church bells to be rung every day at noon for intercession against the comet’s influence.

Eventually, a Danish nobleman would defy superstition and overthrow Aristotle’s lingering ideas. And this end was heralded by a bang.

In November 1572, a “new” star — today we know that star was a supernova — appeared in the constellation Cassiopeia. The young Tycho Brahe was one of the first to make detailed measurements of this event. Brahe could not detect any parallax for the star, which would have been measurable if the object was atmospheric. Brahe’s conclusion was simple: The new star was in heaven itself, within the so-called eighth sphere, the realm of immutability. To those who doubted his findings, he said, “O coecos coeli spectatores,” which roughly translates to “O blind spectators of heaven.”

Five years later, Brahe tested his theory on a newly visible comet. He was now equipped with a private observatory filled with instruments of his own design. Telescopes were still decades away, but he could measure the comet’s course and position with great accuracy. As with the new star of 1572, he found no parallax, placing the comet among the realm of planets. His findings were not accepted by many of his contemporaries, including Johannes Kepler and later Galileo Galilei. Even Brahe himself could not completely shake off the bonds of astrology, making predictions about the comet’s influence on Earth. Nevertheless, Aristotle’s crystalline spheres were soon abandoned.

By the mid-17th century, the Age of Enlightenment was in full bloom. Brahe’s observational work on comets and Kepler’s laws of planetary motion provided novel tools for a new generation of astronomers. Among them was a young man named Edmond Halley.

The most famous comet

Halley’s interest in the cosmos began early in life. When he went to study at the Queen’s College of the University of Oxford, he took a large telescope with him and, as an undergraduate, wrote a handful of papers. In 1676, at the age of 20, he left school and sailed for the island of St. Helena in the Southern Hemisphere. He spent a year mapping the southern sky before publishing his star catalog in 1678. Two years later, he embarked on a grand tour of Europe, visiting observatories and meeting with scientists.

While on his tour, Halley saw the Great Comet of 1680 from Paris. It was discovered by the German astronomer Gottfried Kirch and was the first comet ever found with a telescope. Halley watched the comet brighten into daylight visibility and later develop a tail that stretched some 70°. The Italian astronomer Giovanni Domenico Cassini, who was working at the Paris Observatory, told Halley that he thought comets like this orbited the Sun with predictable accuracy.

In 1682, yet another comet appeared in the sky. Halley and many others, including Isaac Newton, observed this comet closely. Halley kept detailed positional records. At the time, there was still considerable debate about the nature of cometary motion and orbits, but astronomers didn’t have to wait long for a breakthrough. Just two years later, after prodding from Halley, Isaac Newton began work on the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, in which he dedicated considerable discussion to comets.

When Halley worked on cometary orbits in 1685, it was with the Principia at his side. He noted the comets of 1531, 1607, and 1682 had similar orbits. He boldly postulated that they were one and the same, and predicted this comet would reappear at the end of December 1758 — which it did. Unfortunately, Halley did not live to see its return, as he passed away in 1742. But his legacy was cemented at a meeting of the Paris Academy of Sciences in 1759, when astronomer Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille first referred to the body as the name we know it by today: Halley’s Comet.

Unraveling the truth

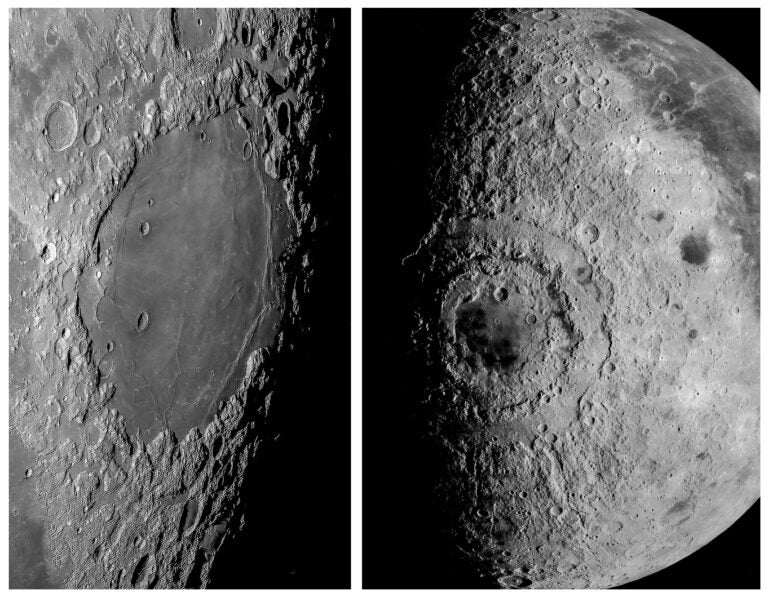

While some have clearly risen to ready recognition, these otherworldly bodies remained a mystery well into the 19th and 20th century. A bumper crop of comets from 1811 to 1882 allowed astronomers to utilize an arsenal of new equipment and technology, with a clue to cometary structure coming in 1826, when astronomers observed Comet Biela (called Gambart’s Comet) with improved telescopes. Calculations showed it was a short-period comet returning about every seven years. But when it was seen again in 1846, the nucleus had split into two separate objects! This gave the first indication that comets were not solid, but instead fragile objects that could be torn apart.

Comets Galore

The 19th century proved a fruitful time for comet hunters, with spectacular shows occurring every few decades.

1811: The Great Comet was visible to the unaided eye for nine months. This was a record that would only be broken by Comet Hale-Bopp when it graced the skies in 1996 and 1997.

1843: In March, a sungrazing comet blazed in the night sky. Also known as the Great March Comet, it inspired wonder worldwide. It was described by the British astronomer Charles Piazzi Smyth as appearing to the naked eye to have “a double tail about 25° in length.”

1858: Giovanni Battista Donati first spotted his namesake comet in early June. It was well placed in the sky for Northern Hemisphere observers. By August, it was visible without optical aid and sported a bright, curving tail.

1882: The Great September Comet dazzled viewers in the Southern Hemisphere. Yet another sungrazing comet, it was first seen Sept. 1, becoming a daylight comet by midmonth. At the comet’s Sept. 17 perihelion pass, it may have reached between magnitude –15 to –20, making it up to a thousand times brighter than the Full Moon!

And as telescope equipment improved, so did photography. In 1840, John W. Draper, an American scientist, captured the first clear image of the Moon. (Though some sources point to French photographer Louis Daguerre as the first to capture Luna, his success is contested, and the fire that destroyed his lab in 1839 makes it impossible to prove.) French physicists Léon Foucault and Louis Fizeau photographed the Sun in amazing detail in 1845 and Draper, along with American astronomer William C. Bond, imaged the star Vega in 1850. All of the images were taken on a daguerreotype. Cometary scientists tried to capture their targets as well, but hazy comas and diaphanous tails proved a challenge. They persevered, however, and finally William Usherwood photographed Comet Donati in 1858. Unfortunately, the image has not survived.

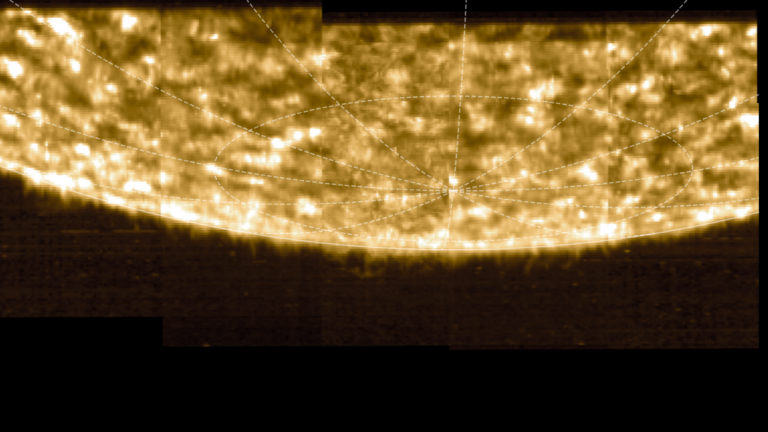

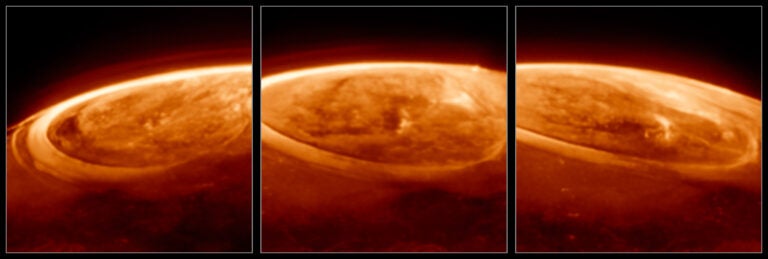

And astronomers didn’t have to wait long for another powerful new tool: the astronomical spectroscope. This instrument could reveal the elements present in stars, nebulae, galaxies, and comets. Giovanni Battista Donati used a spectroscope in 1864 to study Comet Tempel (C/1864 N1). His work showed emission from diatomic carbon in the comet’s spectrum, which ultimately revealed its composition. As spectroscopy improved, astronomers found that the coma of a comet, which surrounds the hidden nucleus, contains vast amounts of dust that is pushed away by the radiant pressure of sunlight. Cometary tails are made of this dust, which reflects sunlight, as well as gases that glow from ionization.

Yet what lay within the dusty veil of the coma remained a mystery. It wasn’t until 1950 that Harvard University astronomer Fred Whipple proposed the “dirty snowball” model for a comet’s nucleus. He suggested that the core of a comet was made of loosely packed ice — a so-called icy conglomerate — protected by a thick layer of dust, dirt, and rock. This model provided an explanation for the dust and gas in a comet’s tails, as well as explaining why the predicted return of a comet could be off by a few days. And, in 1986, when the European Space Agency’s Giotto mission to Halley’s Comet returned images of the comet’s nucleus, they showed Whipple’s model was fundamentally correct.

Around the same time that Whipple proposed his model of the comet’s nucleus, the Dutch astronomer Jan Oort was carefully analyzing the orbits of long-period comets. He found that many comets seem to originate about 20,000 astronomical units (AU; where 1 AU is the average Earth-Sun distance) from our star. This spherical region has become known as the Oort Cloud, and it expanded the bounds of our solar system.

With more than 3,500 comets recognized by NASA today, we now comprehend comets in more detail than we ever thought possible. A better understanding of these comets has relieved some of the fear and superstition that accompanies these celestial visitors as they pass through our night sky. But by no means have they lost their wonder.