The proposal, a collaboration between Draper Laboratories and Cornell University, would utilize a combination of small satellites known as CubeSats and even smaller microprobes called ChipSats to explore Europa on the cheap.

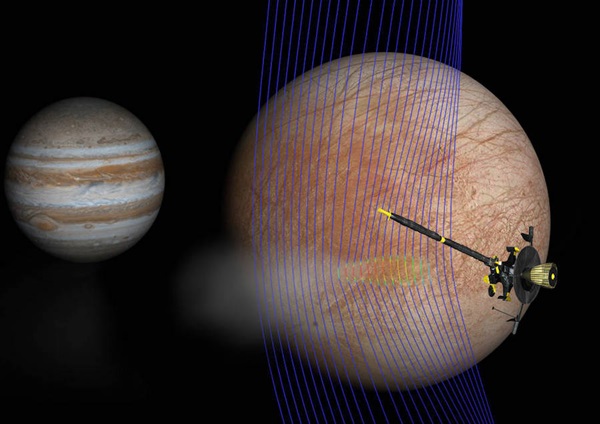

Essentially, a probe consisting of 3 to 12 individual CubeSat units stacked together orbit the icy moon of Jupiter. It has a pretty simple instrument payload: communications equipment and a Cold Atom Sensor, which consists of two chambers of low-temperature atoms. By measuring the tug between each chamber, it can create an effective map of the icy terrain of Europa, measuring ice thickness and finding areas of low ice density to potentially access the ocean below.

The probe would fly just eight miles over the surface of the world, gathering information. Because of the simple instrument payload, it would be well protected from radiation. At some point after it mapped the surface, the probe would then drop thousands of tiny ChipSats onto the surface.

“The hope here is that we actually want to get data from the surface of Europa, and we want to get it from somewhere where it’s interesting,” Brett Streetman, a senior member of Draper’s technical staff, said.

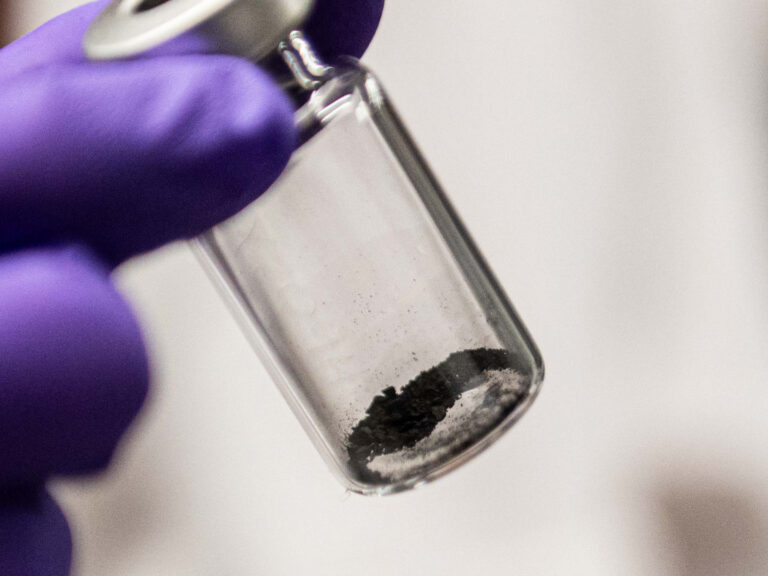

Not all of them would survive the plunge. That’s why there are so many. The harsh radiation may fry out a few more in short order. The ones that do survive, however, would be able to search for amino acids on the surface and determine its chirality, or “handed” ness. If they all seem to go in one direction or the other, it could be a sign of biological processes on Europa.

“In the end, with these ChipSats, we have to boil something down to a yes or no answer, so we need to say ‘yes there’s a strong handedness to the amino acids here,’” Streetman said.

The mission concept was a 2014 Phase I recipient in the NIAC program, and is awaiting word on if it made it to Phase II. The mission is still about 10 to 15 years in the future, however, as cold atom physics is still in its infancy. ChipSats are also not quite as mature as the still-nascent CubeSat technology, with Streetman saying that most tests have looked into communications, merely beeps that “act like Sputnik” as a proof of concept. But once it matures, Streetman said he sees it as a complimentary mission on a larger probe.

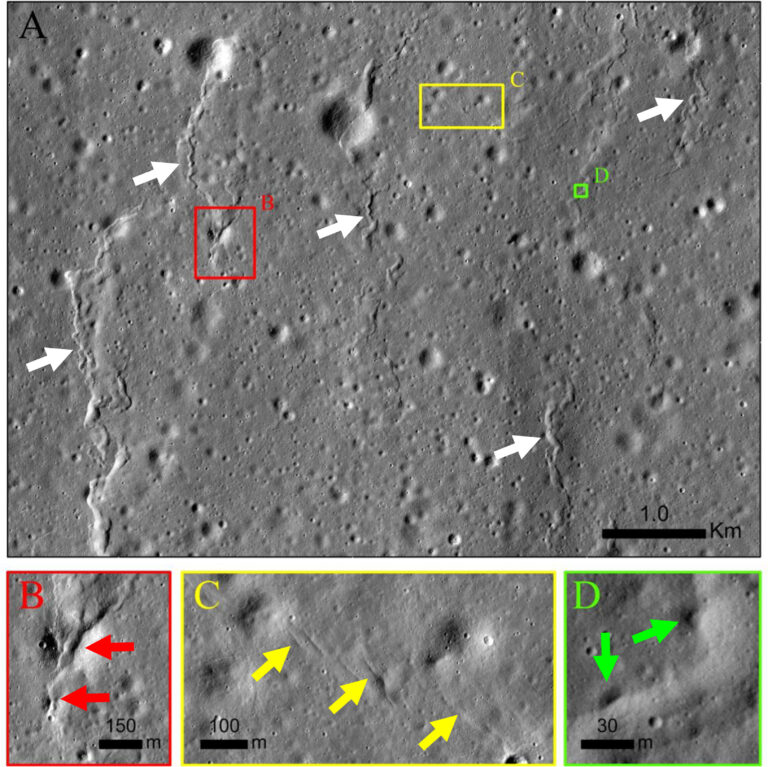

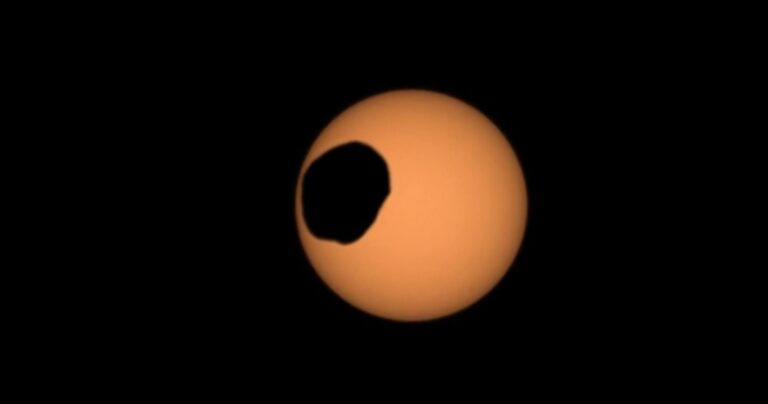

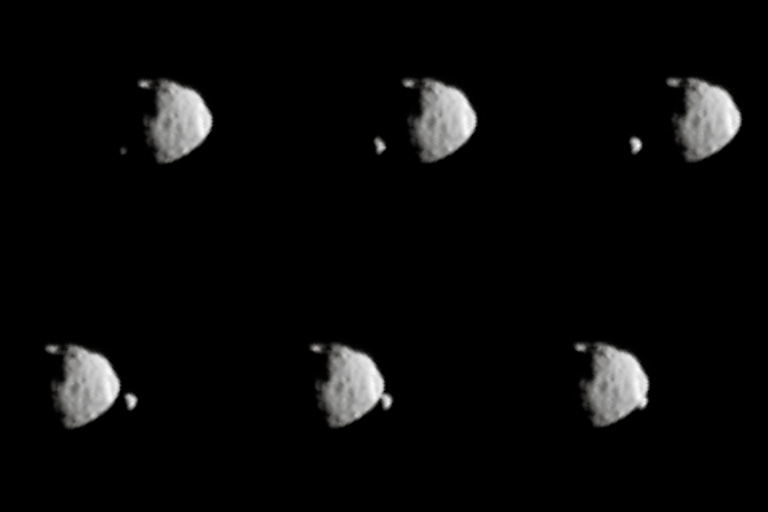

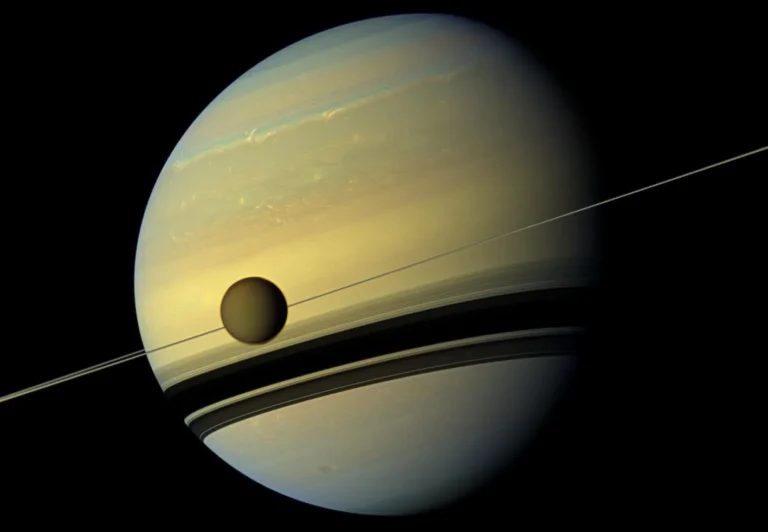

The researchers on the concept have also looked past Europa and thought of other possibilities for the ChipSat / CubeSat teaming, including sending a fleet of ChipSats into Saturn’s ring system to study its composition or measuring seismic activity on asteroids. Draper has also looked at using it to create weather monitors for Titan or Mars.

“We looked at applications around the solar system, and there’s a lot of cool things you can do with the CubeSat platform that you wouldn’t want to do with a traditional spacecraft,” Streetman said.