Key Takeaways:

- On August 8th, the close conjunction of the Moon and Pluto will occur, though Pluto's visibility will be obscured by the Moon's brightness. Observation of the double star Albireo in Cygnus is recommended, noting its contrasting colors.

- August 9th marks the Full Sturgeon Moon. While bright, observation is suggested, focusing on features like the ray systems emanating from craters such as Tycho.

- August 10th offers an opportunity to observe Saturn and its moons, particularly Iapetus, and Mercury's stationary point, signaling the end of its retrograde motion.

- The period from August 11th to 15th includes the observation of asteroid 89 Julia at opposition, the conjunction of Venus and Jupiter, the peak of the Perseid meteor shower, and the observation of M11 (Wild Duck Cluster) and the variable star R Scuti. The article also notes Mercury's increasing visibility and Ceres' stationary point.

Sky This Week is brought to you in part by Celestron.

Friday, August 8

The Moon passes just 0.0009° north of Pluto at 1 A.M. EDT, although our satellite’s bright light will hide the tiny dwarf planet’s dim glow from view.

Tonight, we’re visiting a summertime favorite: the double star Albireo in Cygnus the Swan. Already 60° high in the east an hour after sunset, Albireo — also cataloged as Beta (β) Cygni — marks the head of Cygnus, sitting opposite the brighter star Deneb (Alpha [α] Cyg) at the Swan’s tail. Around 9 P.M. local daylight time, look high in the east to find magnitude 0.0 Vega, Lyra’s brightest star. Drop your gaze about 15.5° below Vega and you’ll land right on 3rd-magnitude Albireo.

Although appearing as one star to the naked eye, a small telescope will reveal this is not one but two stars, separated by 34”. Their lovely contrasting colors of gold and blue are what make them such a popular target. The brighter (golden) star shines at magnitude 3.4, while its fainter (bluer) companion has a magnitude of 5.1. (That brighter star is actually itself two stars, though they cannot be easily separated in a telescope.)

Although most observers do see these stars as yellow and blue, not everyone picks up these hues the same way. Every eye is different, so you might see them as slightly — or very! — different shades. Take some time to enjoy them and consider how you would describe the colors of these two stars.

Sunrise: 6:05 A.M.

Sunset: 8:05 P.M.

Moonrise: 8:06 P.M.

Moonset: 5:01 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (99%)

*Times for sunrise, sunset, moonrise, and moonset are given in local time from 40° N 90° W. The Moon’s illumination is given at 12 P.M. local time from the same location.

Saturday, August 9

Full Moon occurs at 3:55 A.M. EDT this morning. August’s Full Moon is also called the Sturgeon Moon, so named by Native Americans for the prevalence of these fish in late summer.

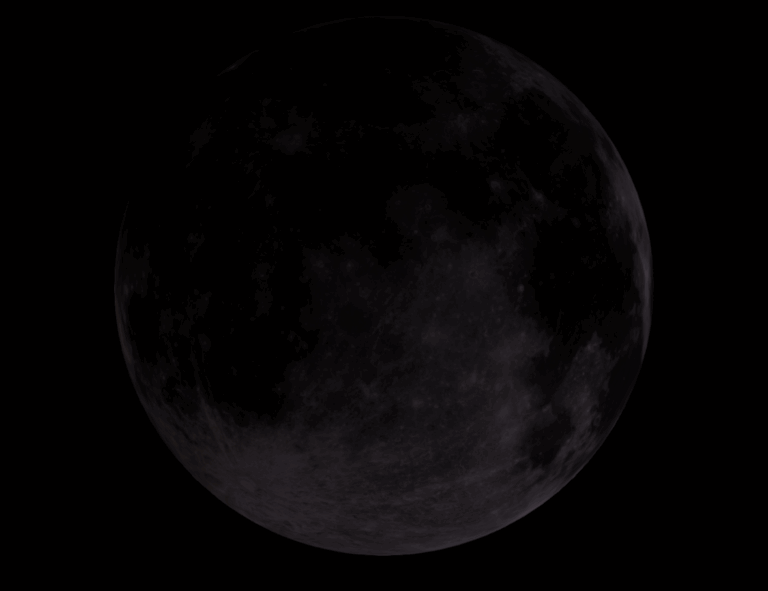

You might think it’s quite easy to observe the Full Moon, but there are a few complicating factors. First, the Full Moon is quite bright, so looking at it through binoculars or at telescope can be uncomfortable (though not dangerous). Further, observing the Full Moon will offset any dark adaptation your eyes have gone through, making it more challenging to see any other objects you want to observe until your vision adjusts once more. And finally, during the Full phase, the Sun appears directly overhead from the lunar perspective — essentially, it is noon on the Moon, and shadows are at their shortest. This can wash out much of the detail on the landscape.

But none of this means the Moon cannot or should not be observed when it’s Full! During this phase, some features are on stunning display, such as the long ray systems streaking away from craters like Tycho, Copernicus, Proclus, and Petit. These rays are ejecta — subsurface material that was excavated and thrown far away during the impact that created these craters.

Tycho, located in the lunar south, has some of of the longest and most impressive rays to observe. The crater stretches some 53 miles (85 kilometers) across, but its rays cover much of the Moon’s nearside, even extending north of the lunar equator. Trace these light-colored rays with your eyes and note how they appear to cover many other features along the way. This means they are younger than the craters, maria, and mountains that lie underneath them. Astronomers estimate Tycho is a mere 110 million years old or so.

Tycho itself has plenty to explore within its bounds, including a central peak rising some 5,000 feet (1,520 meters) above the crater floor. Take your time scanning the region with a small telescope; even under the noontime Sun, there is plenty to observe here.

Sunrise: 6:06 A.M.

Sunset: 8:04 P.M.

Moonrise: 8:34 P.M.

Moonset: 6:13 A.M.

Moon Phase: Full

Sunday, August 10

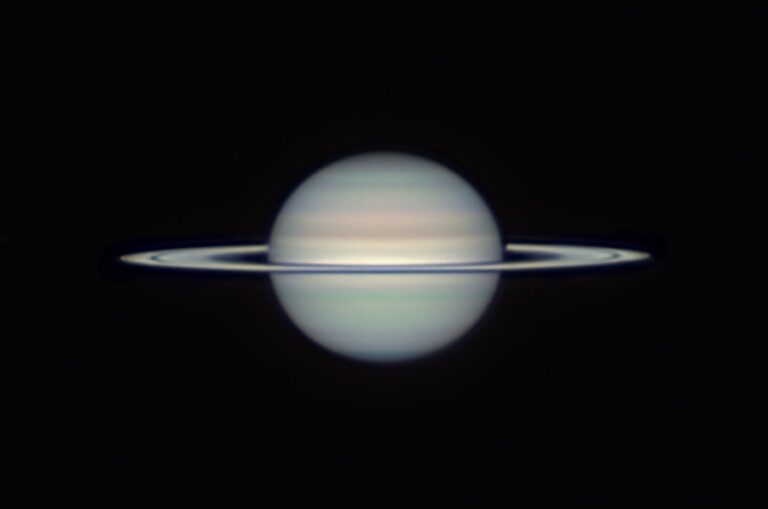

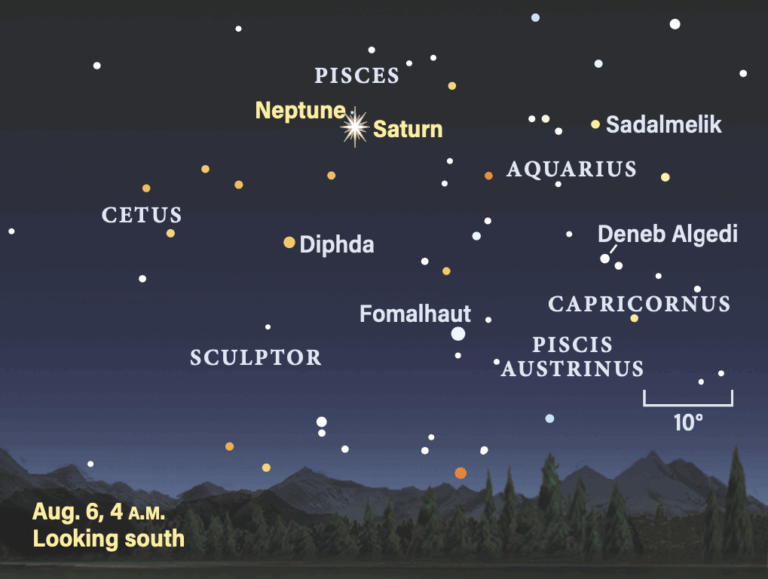

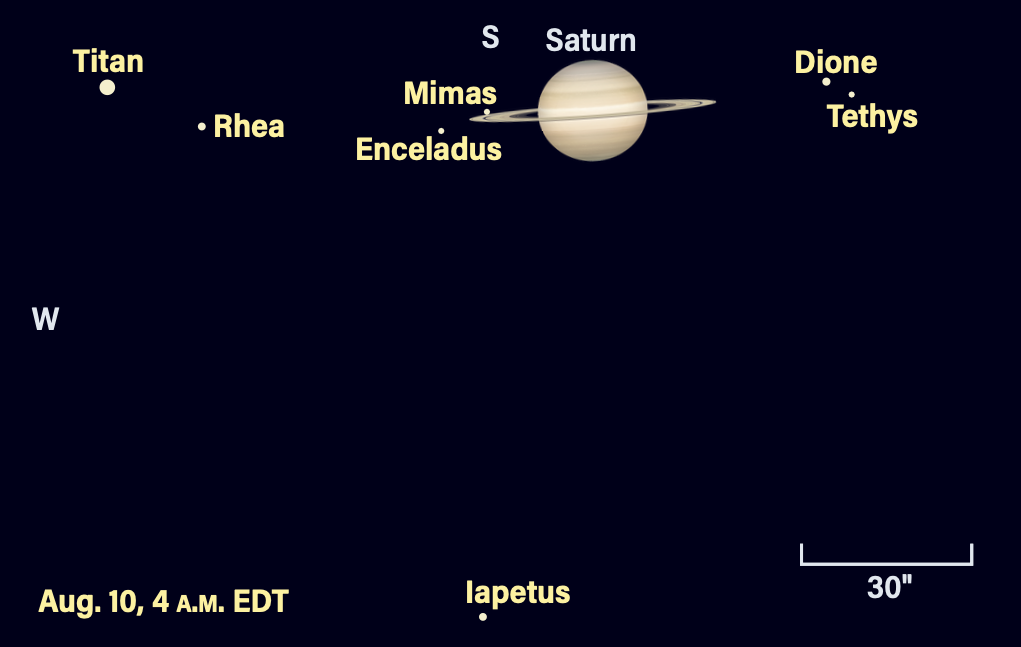

Saturn’s two-toned moon Iapetus stands 1.5′ north of the ringed planet early this morning, shining around 11th magnitude. Spending much of its time far from Saturn, Iapetus rotates in lockstep with its orbit, so that its magnitude changes throughout its orbit as its brighter or darker hemisphere faces us. When it is north or south of Saturn, it is in the middle of this range. Coupled with its proximity to the planet, it’s easier to spot at such times. Give it a try in the early-morning hours — around 4 A.M. local daylight time, Saturn is roughly 45° high in the south, hanging to the lower left of the Circlet asterism in Pisces. At magnitude 0.7, the planet is the brightest point of light in this region of the sky.

Use a telescope to zoom in on the gas giant and enjoy the view of its rings as well as several of its larger, brighter moons. The largest and brightest of those satellites, 8th-magnitude Titan, lies west of the planet. Closer in on that side, you may also spot 10th-magnitude Rhea. Eleventh-magnitude Iapetus is slightly northwest of the planet early this morning. Tethys and Dione, both 10th magnitude, lie east of Saturn. There are several other moons as well, but they are fainter than 11th magnitude and thus more difficult to see. You could try for 12th-magnitude Enceladus just west of the rings if you have a larger scope and clear skies.

Mercury is stationary at 2 P.M. EDT, bringing its retrograde motion to an end. Now in Cancer the Crab, the solar system’s smallest planet will begin moving prograde, or eastward, against the background stars, passing south of the Beehive Cluster in the central regions of this constellation later this month. Mercury currently rises shortly after the Sun, but give it a few more days and it will be visible in the predawn hours. We’ll view it later this week.

Sunrise: 6:07 A.M.

Sunset: 8:03 P.M.

Moonrise: 9:00 P.M.

Moonset: 7:25 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waning gibbous (98%)

Monday, August 11

Asteroid 89 Julia reaches opposition at 5 A.M. EDT. Shining at magnitude 8.5, it’s easily reachable with binoculars or any telescope. The best time to view it will be this evening, so let’s stop first in the early-morning sky, where Venus and Jupiter now rise just 1.2° apart, closing in for their formal conjunction tomorrow, when less than 1° will separate them.

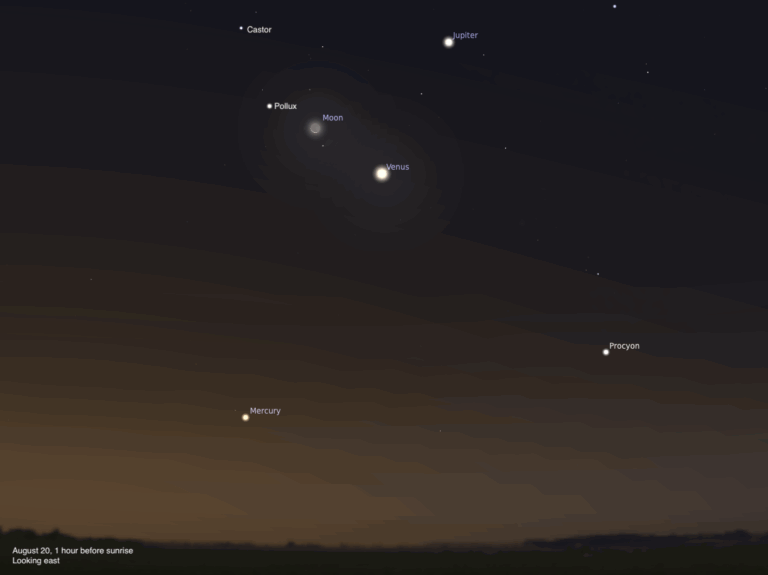

An hour before sunrise, the pair of planets is 20° high in the east, between the two bodies of Gemini. To their left are Castor and Pollux, the Twins’ brightest stars, stacked on top of each other as the constellation rises (Castor is higher). Jupiter is just left of Venus, with the gas giant glowing a bright magnitude –1.9 — but it’s outdone by brighter Venus, at magnitude –4.0. Check out both with the naked eye and through binoculars or a telescope. They’re close enough to appear within a single field of view, and tomorrow they will be even closer. We’ll definitely come back then.

This evening, let’s get back to Julia, which rises around sunset and is visible all night, reaching its highest point around 1 A.M. local daylight time. A few hours earlier, though, around 11 P.M. local daylight time, Julia is 30° high in the southeast, located in western Aquarius. You can find the main-belt world in binoculars or a telescope, just over 2° due east of magnitude 4.5 Nu (ν) Aquarii.

As a bonus, M73 lies nearby, some 4.8° west-southwest of Julia tonight. Shining at magnitude 9.0, this object probably isn’t a true open cluster but more likely a chance superposition of four stars, shining between magnitude 10 and 12. If you want to view a cluster that is truly real, though, you don’t have to look much farther: 1.5° west of M73 is magnitude 9.3 M72, a compact globular cluster. It may appear mostly like a smudge of light, as larger telescopes (8 inches or more) are really needed to begin resolving its tightly packed stars.

Sunrise: 6:08 A.M.

Sunset: 8:01 P.M.

Moonrise: 9:24 P.M.

Moonset: 8:36 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waning gibbous (93%)

Tuesday, August 12

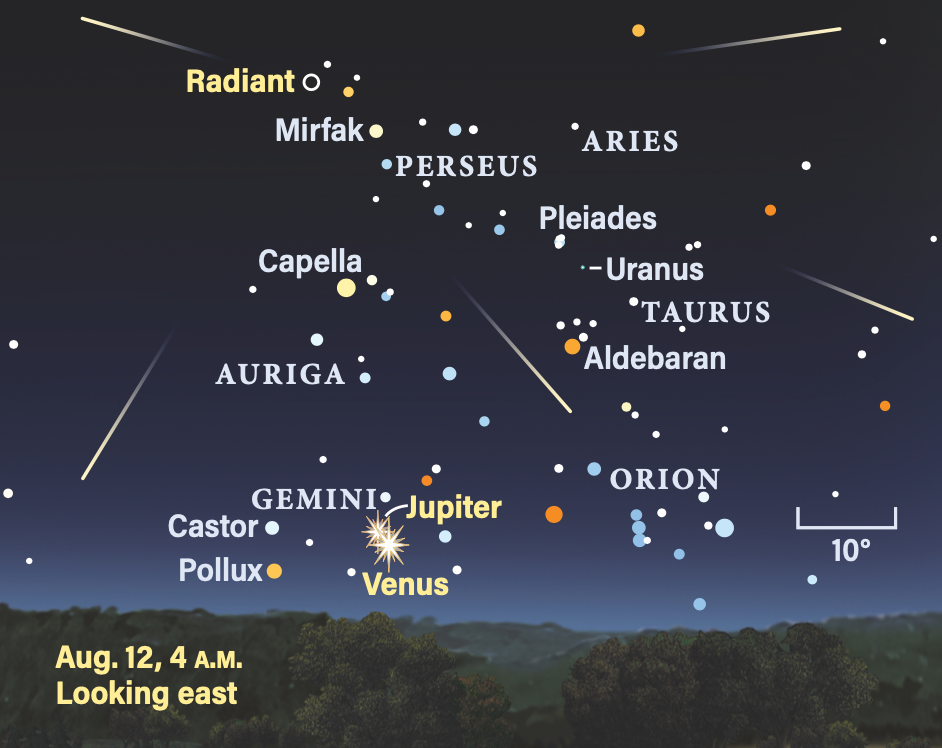

This morning is a busy one: Venus passes 0.9° south of Jupiter at 4 A.M. EDT, the two planets officially meeting in a conjunction as the Perseid meteor shower peaks.

Step outside at 4 A.M. local time to catch the show. At that time, Venus and Jupiter are some 7° high in the east, located centrally in Gemini the Twins. Venus is the brightest object in the sky, blazing at magnitude –4.0. Jupiter, which sits just to Venus’ upper left, is no slouch at magnitude –1.9. The two bright points of light will be unmissable in the early-morning sky, with the Twins’ brightest two stars, Castor and Pollux, shining to their left. Pollux, which sits closer to the horizon as Gemini rises, is just slightly brighter than Castor, which appears above it.

Through binoculars or a telescope, both planets should be visible in the same field of view. A telescope will reveal even more detail: Venus spans 13” and appears 79 percent lit. Jupiter stretches roughly twice that, at 33” across, with its four Galilean moons on display. By 4 A.M. EDT, Callisto lies alone to Jupiter’s east. Io is close to the planet’s western limb, having completed a transit of the planet’s disk roughly 20 minutes earlier. Farther west lie Europa and then Ganymede.

As you’re gazing at the planets, make sure to take some time to scan the sky for shooting stars, as the annual Perseid meteor shower peaks this morning. The bright Moon will unfortunately interfere, but the Perseids often produce bright meteors, meaning the best of what the shower has to offer should still be visible. By 4 A.M. local daylight time, the shower’s radiant is 50° high in the east, near the star Mirfak. Looking some ways away from this point will up your chances of spotting meteors with long, bright trains. You can expect to see about a dozen meteors per hour, given the sky conditions this morning.

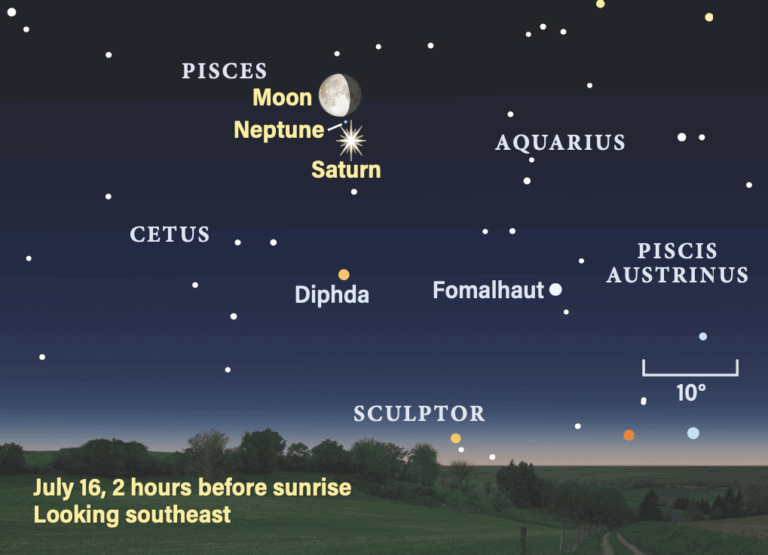

That bright Moon stands 3.5° northwest of Saturn in Pisces before dawn, high in the southern sky. Neptune — invisible without binoculars or a telescope, and even then difficult because of the moonlight — is 1.2° north of Saturn.

The Moon will pass 4° north of Saturn at 11 A.M. EDT, then slide 3° north of Neptune at noon EDT.

Sunrise: 6:09 A.M.

Sunset: 8:00 P.M.

Moonrise: 9:47 P.M.

Moonset: 9:49 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waning gibbous (86%)

Wednesday, August 13

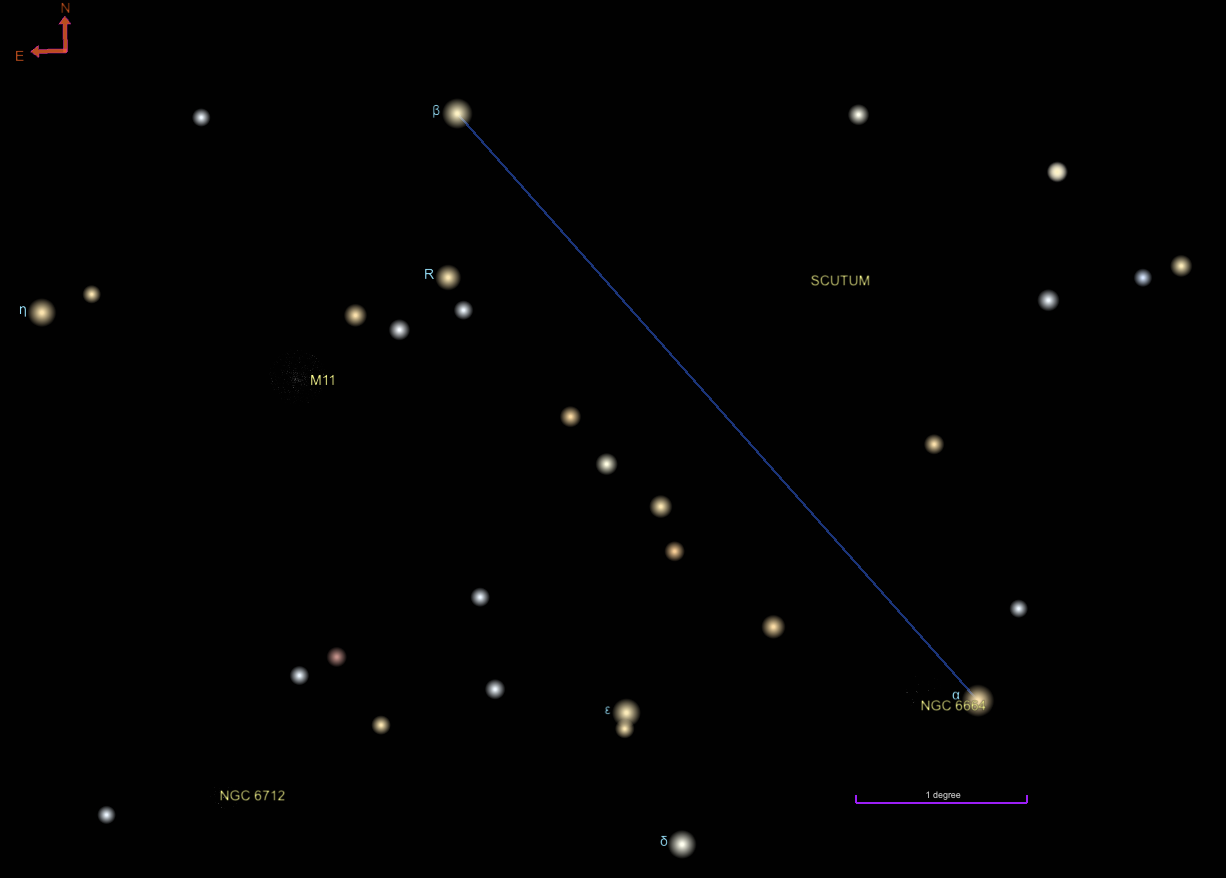

The Wild Duck Cluster, also cataloged as M11, flies high in Scutum this evening about two hours after sunset. Around 10 P.M. local daylight time, you can find it some 40° high in the south, some 3° west-southwest of the tail feathers of Aquila the Eagle.

As an open cluster, M11’s stars are young, estimated at about 250 million years old. Shining collectively at magnitude 5.8, M11’s nearly 3,000 suns cover a region about half the size of the Full Moon and can be spotted in binoculars or any size telescope. This is a great beginner object, with several dozen stars visible in even small beginner scopes. The cluster’s common name comes from astronomer William Henry Smyth, who thought it looked like a flock of wild birds in flight.

About 1° northwest of this cluster is R Scuti, a famous variable star whose brightness swings between magnitudes 4.5 and 8.2 over the course of about 140 days. That means sometimes it is visible to the naked eye, and sometimes it is not. Check out the star chart above to see whether you can identify R Sct with and without optical aid.

Sunrise: 6:10 A.M.

Sunset: 7:59 P.M.

Moonrise: 10:12 P.M.

Moonset: 11:01 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waning gibbous (77%)

Thursday, August 14

The Moon reaches perigee at 1:59 P.M. EDT. Perigee is the point in the Moon’s orbit when it is closest to Earth; this afternoon, our satellite will sit 229,456 miles (369,274 km) away.

Mercury is just starting to emerge from the Sun’s glare, presenting a challenging but reachable target. Now shining at magnitude 1, the tiny planet is 3° high in the eastern sky an hour before sunrise. It lies in Cancer the Crab, just east of Gemini, which currently houses Venus and Jupiter. You can use these bright planets to sketch out the ecliptic in your mind and point your way to Mercury. The ecliptic is the plane of Earth’s orbit around the Sun; since the major planets all orbit close to the ecliptic, they appear to line up in our sky. So, when multiple planets appear in the sky, you can use bright worlds to point toward fainter ones.

Start with Jupiter, which is highest in the east, just to the upper right of brighter Venus. Draw a line between these two points of light and follow it down toward the horizon. There’s where you’ll find Mercury — as mentioned, 3° high an hour before sunrise. You can use binoculars or a telescope to more easily locate the dimmer world, which spans 9” and now appears 24 percent lit through a telescope.

Mercury will continue to brighten over the next few days, moving slowly toward central Cancer and the Beehive Cluster (M44). In just five days, it will reach magnitude 0, then share the sky with a crescent Moon two days later.

Sunrise: 6:11 A.M.

Sunset: 7:58 P.M.

Moonrise: 10:41 P.M.

Moonset: 12:15 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waning gibbous (67%)

Friday, August 15

Dwarf planet 1 Ceres is stationary at 9 P.M. EDT, though to spot it you’ll have to get up early, as it’s only visible in the morning sky.

Around 4 A.M. local daylight time, Ceres is just over 40° high in the southern sky. The main belt’s largest body is currently making its way through Cetus the Whale in a region to the lower left of Saturn, which is the brightest point light visible to the naked eye in southwestern Pisces. This morning, Ceres is not far from magnitude 3.6 Theta (θ) Ceti. At magnitude 8.4, Ceres is not visible to the naked eye; with binoculars or a telescope, you’ll want to look for the dwarf planet some 2° north-northeast of Theta Cet.

Note that today, Ceres also stands just 4.5’ southeast of a magnitude 6.8 background star, forming a wide “double star.” Ceres is the dimmer of the two.

This stopping point marks a turnaround in Ceres’ motion. Previously it was moving eastward, or prograde, relative to the background stars. Now it will begin to move westward, or retrograde. When objects appear to “stop” in our sky, their motion isn’t actually changing — instead, Earth is either passing them by or falling behind as both objects orbit the Sun.

Sunrise: 6:12 A.M.

Sunset: 7:56 P.M.

Moonrise: 11:15 P.M.

Moonset: 1:32 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waning gibbous (56%)