Key Takeaways:

- SpaceX's Starship Version 2 (V2) successfully completed its 11th and final test flight, achieving reentry and splashdown, and providing critical data after a series of earlier developmental challenges.

- The company is transitioning to an upgraded Version 3 (V3) Starship in early 2026, designed with larger propellant tanks, enhanced Raptor engines, and an increased payload capacity of up to 150 metric tons.

- V3 Starship development is crucial for enabling orbital missions, rapid reuse, and in-orbit propellant transfer demonstrations, capabilities vital for NASA's Human Landing System (HLS) for lunar missions.

- SpaceX is expanding its manufacturing and launch infrastructure, including new pads at Starbase and facilities at Kennedy Space Center, to support mass production and significantly increase Starship's launch cadence.

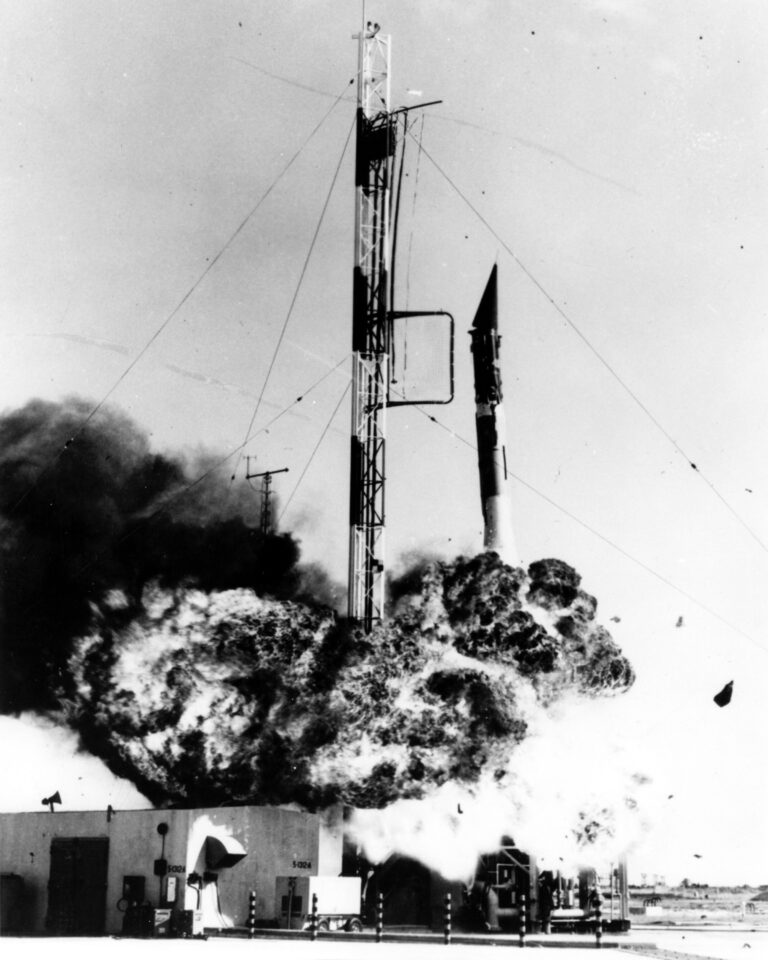

SpaceX’s Starship rocket successfully completed its 11th test flight on Monday, capping a tumultuous year for the hulking vehicle as the company looks to push the envelope with a more powerful configuration.

Monday’s test continued Starship’s return to form, marking its second consecutive reentry and splashdown following a string of in-flight and test stand mishaps. It was Starship’s final flight of 2025 and the swan song for the rocket’s Version 2 (V2) configuration, which SpaceX intends to replace with an upgraded Version 3 (V3) in early 2026.

According to SpaceX, Flight 11 “reached every objective, providing valuable data as we prepare the next generation of Starship” and the Super Heavy booster. The V3 Starship is expected to open the door to orbital missions, rapid reuse, and in-orbit demonstrations of propellant transfer between ships — all critical capabilities for the Starship human landing system (HLS) that could put NASA astronauts on the moon as soon as mid-2027.

Jake Berkowitz, a SpaceX lead propulsion engineer, said on the Flight 11 livestream that the company is assembling multiple V3 Starships and preparing for testing. “Nearing completion,” Berkowitz said, is a second launch pad at its Starbase facility in Texas that is designed to accommodate the larger, more powerful rocket with the addition of a flame trench.

“Both the pad and the vehicles are going to roll in really significant changes, building on everything we’ve learned from all of these flight tests to make a vehicle that we’re looking to mass produce,” Berkowitz said.

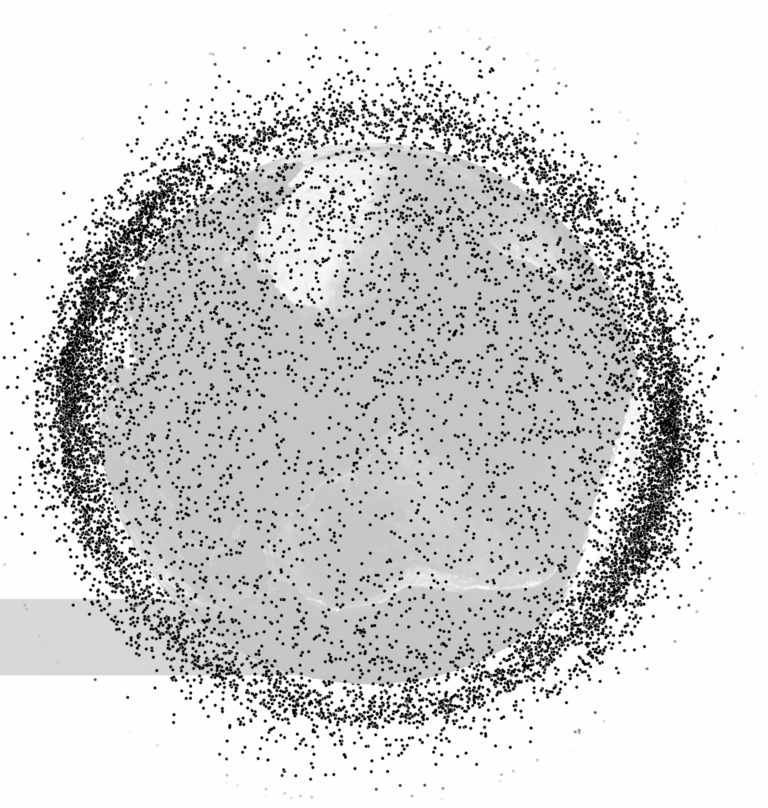

SpaceX will also modify the existing Starbase launch pad for the V3, giving it two pads that could be used to ramp up Starship’s launch cadence from months to weeks — or even days. A Starship HLS lunar landing will require several launches in quick succession to stock up an orbital fuel tank. Before that happens, SpaceX will need to prove the capability in testing.

Starship’s return to form

Though Starship has not had the year that SpaceX would have hoped, the company appears to be learning from its failures.

The rocket began 2025 in explosive fashion, blowing up during its ascent and diverting air traffic on back-to-back flights in January and March. Flight 9 in May marked an improvement as Starship avoided issues on the way up. But it once again failed to make it to reentry and splashdown — the phase of the mission during which SpaceX hoped to gather key data on the performance of its heat shield. Hiccups continued into June, when the ship intended for Flight 10 exploded on the test stand.

SpaceX dissected these anomalies and found different root causes for each, making several improvements ahead of Flight 10 in late August. They were effective, allowing Starship to deploy its first payload — a batch of dummy Starlink satellites—and achieve splashdown for the first time in 2025.

Flight 11 continued that upswing. Starship and Super Heavy lifted off from Starbase around 6:23 p.m. EDT on Monday. On the way up, Starship jettisoned the booster, which completed a boostback burn and headed back to Earth. SpaceX has previously caught Super Heavy back at the pad using a pair of giant metal chopsticks.

But Flight 11, like the previous mission, tested maneuvers that are planned for the V3 booster. Super Heavy on Monday ignited 13 of its 33 Raptor engines before shifting down to five, then three. It hovered a few hundred feet over the ocean before engine cutoff.

Starship, meanwhile, reached its suborbital trajectory, opened its payload bay, and released another batch of Starlink simulators. These were meant to imitate SpaceX’s larger, next-generation Starlink modules, which can only launch on Starship.

The rocket also relit one of its six Raptor engines on orbit for the third time. Future missions will require that capability to maintain orbital control.

Starship’s crowning achievement, though, was surviving a reentry profile intended to push the rocket to its limits.

As it did ahead of previous flights, SpaceX for Flight 11 removed some of the heat shield tiles protecting Starship’s stainless steel body. The idea is to “stress-test” vulnerable portions of the heat shield that experience temperatures north of 2,600 degrees Fahrenheit while hurtling through the atmosphere.

The ship made it through reentry without significant damage visible on SpaceX’s live feed, which should give the company valuable data. It also performed what SpaceX described as a “dynamic banking maneuver” that mimicked the trajectory it would take leading up to a catch attempt at Starbase. These tests could facilitate the eventual catch and rapid reuse of Starship — a capability SpaceX has already demonstrated with Super Heavy.

Following the bank maneuver, Starship floated down to Earth on its side, as if preparing for a belly flop. It then performed a landing flip and burn, splashing down softly at a preplanned location in the Indian Ocean.

Mishaps during previous test flights have placed SpaceX in a time crunch. According to a Government Accountability Office assessment of major NASA projects, the space agency predicts with 70 percent confidence that Starship HLS will be ready by February 2028 — months after it is scheduled to facilitate the Artemis III lunar landing.

In November, for example, Kathy Lueders, general manager of Starbase, said the company hoped to catch Starship as soon as May. That is unlikely to happen until SpaceX has at least a few V3 launches under its belt. But the more robust rocket has the potential to unlock reusability, which SpaceX CEO Elon Musk has dubbed the “holy grail” of rocketry.

What’s new with V3?

Starship V2 debuted on Flight 7 in January, introducing new capabilities—and complexities—to the design. Now that SpaceX has had a few months to iron out the kinks, it is preparing to usher in what could be the rocket’s operational era.

Starship V3 will introduce larger propellant tanks, upgraded Raptor engines, and a payload fairing larger than any in operation. It is projected to carry up to 150 metric tons of payload — more than NASA’s Apollo-era Saturn V — for longer distances and a lower cost than SpaceX’s workhorse Falcon 9.

The company envisions V3 launching satellites and small telescopes to orbit. According to its website, research, development, and exploratory flights to the moon and Mars will begin in 2028 and 2030, respectively, priced at $100 million per metric ton of cargo.

Another V3 upgrade is the installation of docking adapters for the on-orbit transfer of cryogenic propellant between ships. SpaceX hopes to demonstrate that maneuver next year, launching two Starships weeks apart. In the future, Starship tankers will restock an orbital propellant depot that will be used to fuel up for missions to the moon and Mars.

Beyond the rollout of V3, SpaceX is preparing for Starship mass production. Development, manufacturing, and testing for the rocket takes place at Starbase, where the Starfactory manufacturing hub is being developed to churn out up to 1,000 Starships per year.

At the same time, SpaceX is building a pair of Starship integration buildings called Gigabays—one next to Starfactory, and a second at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Both are expected to be completed in 2026. These facilities would allow Starship to launch from Starbase as well as Florida’s Space Coast, where SpaceX is seeking permission to use KSC’s Launch Complex 39A and Cape Canaveral Space Force Station’s Space Launch Complex 37.

Ultimately, the goal is to launch hundreds of Starships annually from multiple pads. But first, SpaceX will need to solve the heat shield dilemma.

Editor’s note: This story first appeared on FLYING.