Key Takeaways:

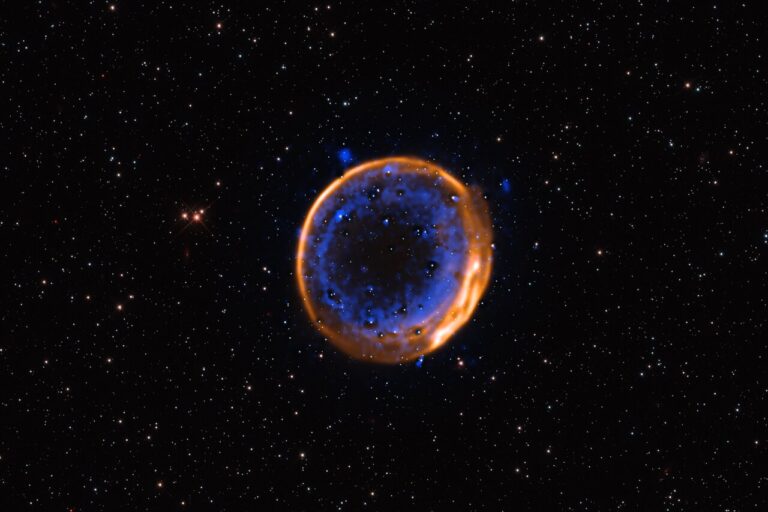

This February 24, we celebrate the 50th anniversary of their game-changing paper and the many discoveries surrounding pulsars that have ensued over the years. That first paper proposed “a tentative explanation of these unusual sources in terms of the stable oscillations of white dwarf or neutron stars;” we now know that pulsars (a term coined separately in 1968) are indeed rotating neutron stars beaming radiation from their poles. Neutron stars, the remnants of supernovae, are randomly oriented in space — but sometimes, they’re oriented just right, and their beams sweep over Earth, much like the light from a lighthouse.

You can learn more about these amazing objects and their discovery in our exclusive online bonus feature: Pulsars at 50: Still going strong, which appeared in our May 2017 issue. In honor of the anniversary, we’ve also pulled together several additional online news and bonus features to help you unlock the mysteries of our universe’s most precise and long-lasting radio beacons.

The sounds of pulsars

Want to know what a pulsar sounds like? The Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics has several recordings of the radio signals from famous pulsars available online.

Exploring the pulsar zoo

Take a look at the many subclasses of pulsars, each of which helps astronomers better understand how stars live and die.

Pulsar planets

The first extrasolar planets were found not circling a Sun-like star, but orbiting a stellar remnant — a pulsar.

Pulsars: The universe’s gift to physics

What have pulsars taught astronomers about how the universe works? A lot!

New pulsar result supports particle dark matter

One of the most recent and most exciting findings involving pulsars lends credence to the idea that dark matter is composed of particles.

Future spacecraft can use pulsars to navigate completely autonomously

What do you do in deep space without GPS? NASA is looking to use pulsar signals to navigate.

Pulsar web could detect gravitational waves

Pulsars could help astronomers learn more about gravitational waves and more accurately test Einstein’s theories.

Astronomers discover a white dwarf that acts like a pulsar

Pulsars are spinning neutron stars … but new evidence suggests white dwarfs can act as pulsars, too.

More about magnetars

Magnetars are an extreme type of neutron star, and we think they’re responsible for fast radio bursts.

Black widow star destroys its mate

Pulsars in binary systems may seal the fate of the stars they’re paired with.

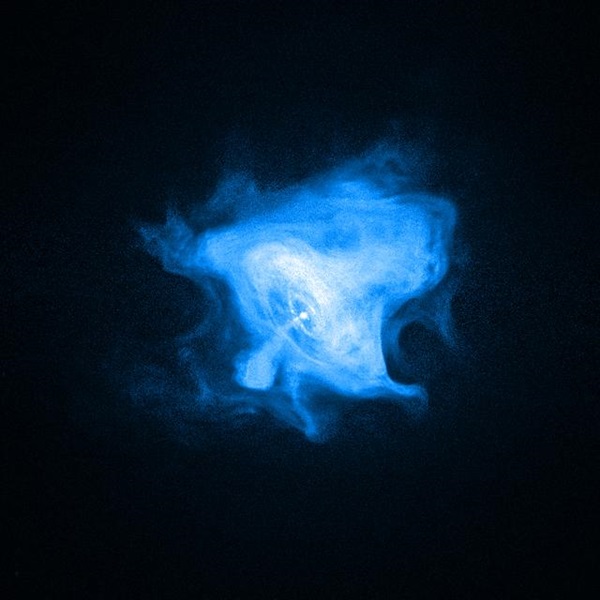

Crab Nebula

This famous Messier object houses a pulsar with something unique: a well-known history.

Ask Astro: Millisecond pulsars

Why do we see a flash instead of a constant signal from a millisecond pulsar, which spins 20-700 times per second? Is that not fast enough to maintain a steady beam of light?

Would you like to learn more? Check out our free downloadable eBook: Exotic objects: Black holes, pulsars, and more