Key Takeaways:

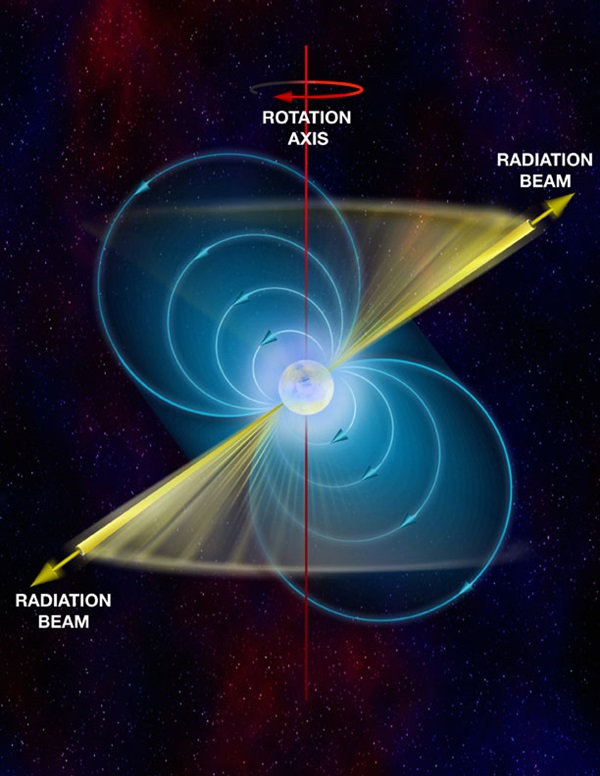

Neutron stars are the remnants of massive stars that exploded as supernovae. They pack more than the mass of the Sun into a sphere no larger than a medium-sized city, making them the densest objects in the universe, except for black holes, for which the concept of density is theoretically irrelevant. Pulsars are neutron stars that emit beams of radio waves outward from the poles of their magnetic fields. When their rotation spins a beam across Earth, radio telescopes detect that as a “pulse” of radio waves.

By precisely measuring the timing of such pulses, astronomers can use pulsars for unique “experiments” at the frontiers of modern physics.

Pulsars are at the forefront of research on gravity. Albert Einstein published his general theory of relativity in 1916, and his description of the nature of gravity has, so far, withstood numerous experimental tests. However, there are competing theories.

“Many of these alternate theories do just as good a job as general relativity of predicting behavior within our solar system. One area where they differ, though, is in the extremely dense environment of a neutron star,” said Ingrid Stairs from the University of British Columbia in Canada.

In some of the alternate theories, gravity’s behavior should vary based on the internal structure of the neutron star.

“By carefully timing pulsar pulses, we can precisely measure the properties of the neutron stars. Several sets of observations have shown that pulsars’ motions are not dependent on their structure, so general relativity is safe so far,” Stairs said.

Recent research on pulsars in binary-star systems with other neutron stars, and, in one case, with another pulsar, offers the best tests yet of general relativity in strong gravity. The precision of such measurements is expected to get even better in the future, Stairs said.

Another prediction of general relativity is that motions of masses in the universe should cause disturbances of space-time in the form of gravitational waves. Such waves have yet to be directly detected, but study of pulsars in binary-star systems have given indirect evidence for their existence. That work won a Nobel Prize in 1993.

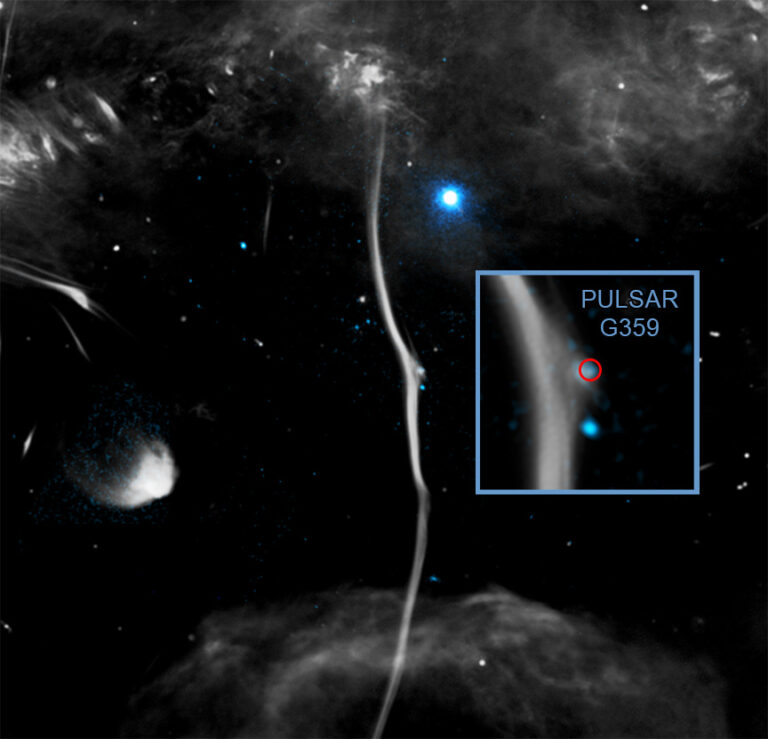

Now, astronomers are using pulsars throughout our Milky Way Galaxy as a giant scientific instrument to directly detect gravitational waves.

“Pulsars are such extremely precise timepieces that we can use them to detect gravitational waves in a frequency range to which no other experiment will be sensitive,” said Benjamin Stappers from the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom.

By carefully timing the pulses from pulsars widely scattered within our galaxy, the astronomers hope to measure slight variations caused by the passage of the gravitational waves. The scientists hope such pulsar timing arrays can detect gravitational waves caused by the motions of supermassive pairs of black holes in the early universe, cosmic strings, and possibly from other exotic events in the first few seconds after the Big Bang.

“At the moment, we can only place limits on the existence of the very low-frequency waves we’re seeking, but planned expansion and new telescopes will, we hope, result in a direct detection within the next decade,” Stappers said.

With densities as much as several times greater than that in atomic nuclei, pulsars are unique laboratories for nuclear physics. Details of the physics of such dense objects are unknown.

“By measuring the masses of neutron stars, we can put constraints on their internal physics,” said Scott Ransom from the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Socorro, New Mexico. “Just in the past three to four years, we’ve found several massive neutron stars that, because of their large masses, rule out some exotic proposals for what’s going on at the centers of neutron stars.”

The work is ongoing, and more measurements are needed. “Theorists are clever, so when we provide new data, they tweak their exotic models to fit what we’ve found,” Ransom said.

Pulsars were discovered in 1967, and that discovery earned the Nobel Prize in 1974.