But Earth’s north magnetic pole is on the move. That motion, combined with several other factors, has led some scientists to wonder whether a magnetic pole reversal — when the north and south magnetic poles switch places — is on the horizon.

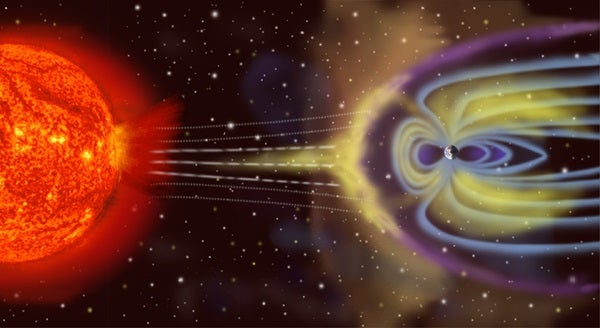

When the poles do shift, other changes occur: Earth’s magnetic field loses some 90 percent of its strength during a reversal, potentially exposing the planet to higher amounts of solar and cosmic radiation.

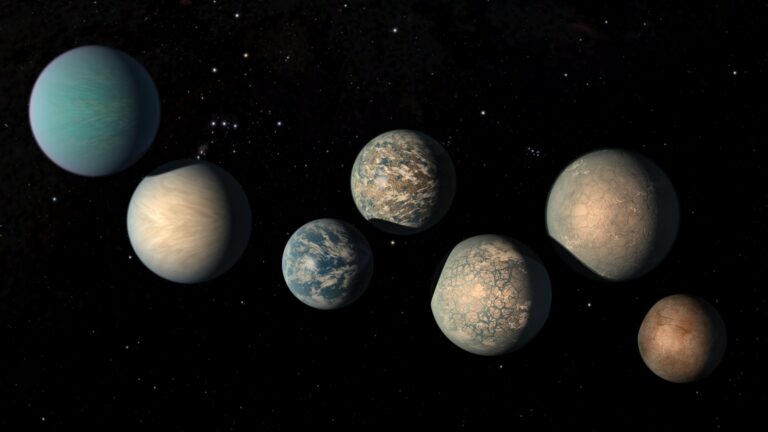

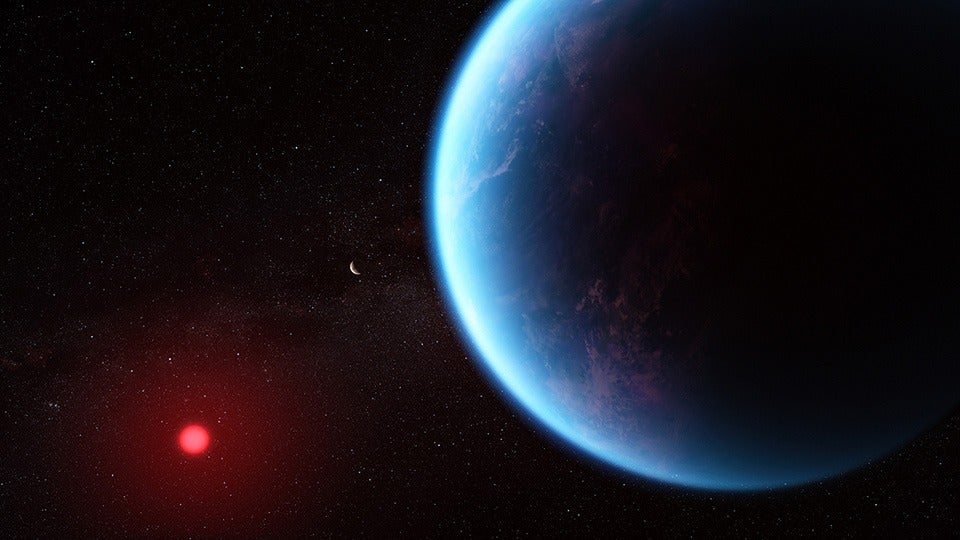

The same, scientists think, is likely true on extrasolar planets as well. That means understanding other planets’ magnetic fields is vital when evaluating whether the worlds we find circling other stars are potentially habitable or not.

Not alone in the cosmos

Little is known about why pole reversals happen in the first place, Jonathan Mound, an associate professor at the University of Leeds, U.K., told Astronomy in 2017.

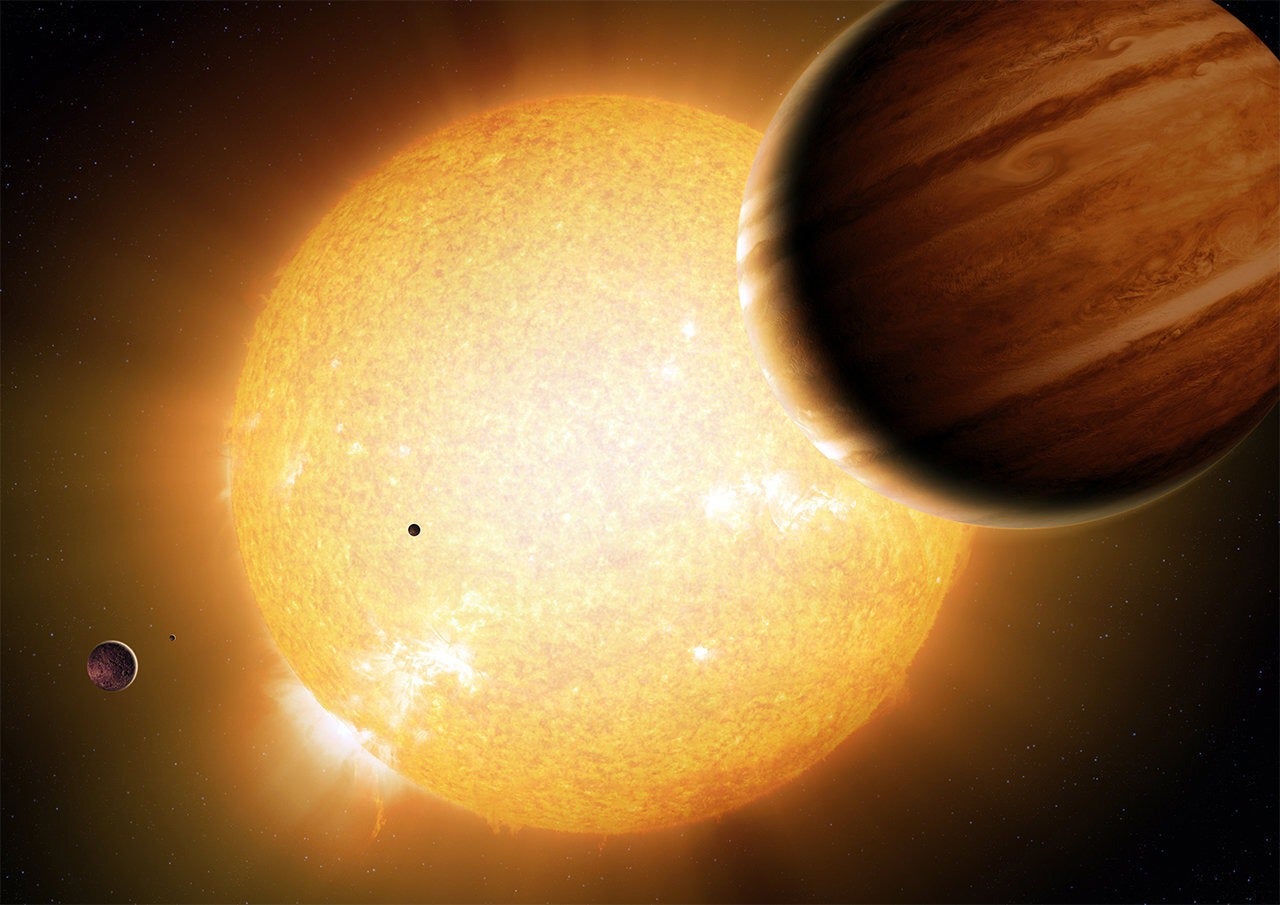

But while scientists don’t know why reversals occur, they do know Earth is not alone in experiencing them. Magnetic field reversals occur on Jupiter and Saturn as well. Outside the solar system, it is “quite plausible” that exoplanets with Earth-like interiors may experience pole reversals, says Manasvi Lingam, an assistant professor at the Florida Institute of Technology.

On Earth, reversals occur once every several hundred thousand years. That’s pretty frequent in geologic timescales. Jupiter and Saturn’s reversals happen faster still — on the order of centuries. But despite frequent reversals causing a periodic drop in magnetic field strength and an increase in solar radiation, the outcome clearly has not been catastrophic on existing life on Earth.

Still, understanding how frequently exoplanets’ magnetic fields flip or vary is crucial when characterizing their habitability.

Lingam has investigated the influence of varying magnetic fields on exoplanets orbiting red dwarf stars. He says many of the same effects expected to occur on Earth during reversals may also occur on exoplanets when their fields flip. Even when the field isn’t reversing, magnetic poles might wander, and that behavior would impact habitability in subtle ways. But the large number of unknowns makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions.

“What we can say with some confidence is that suppressing magnetic fields will lead to higher quantities of radiation and potentially higher rates of atmospheric erosion by the stellar wind,” explains Lingam, who explores these questions surrounding habitability in his upcoming book, Life in the Cosmos: From Biosignatures to Technosignatures. “Recent research suggests that neither of these trends is drastic enough to suppress habitability altogether.”

Seeing is believing

The first step to observing reversals is to detect magnetic fields on exoplanets, which in itself is a challenge.

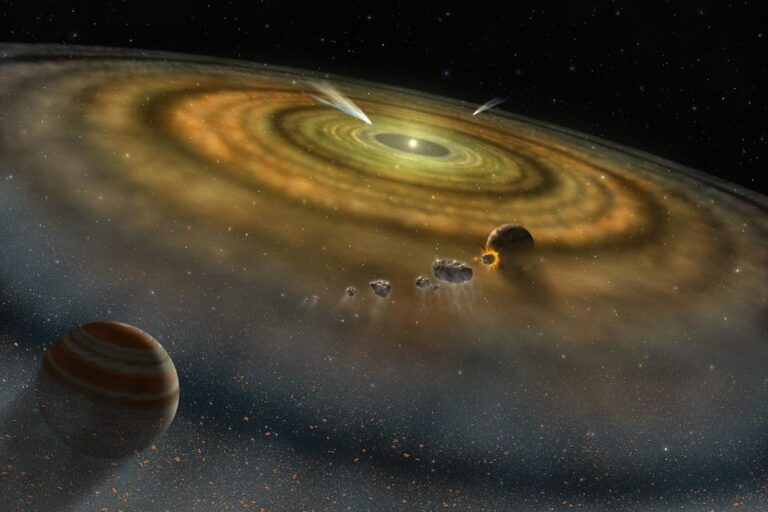

“Of the 4,000 planets [we’ve detected so far], we’ve really only looked for magnetic fields on maybe 15 or less,” says Evgenya Shkolnik, an associate professor of astrophysics at the Arizona State University and an expert on exoplanets and the disks of material that form them.

The exoplanets whose magnetic fields are under scrutiny are hot Jupiters, Shkolnik says. These are exoplanets that are physically similar to Jupiter but much closer to their stars, often orbiting in a matter of days at distances less than that of Mercury from the Sun.

Astronomers currently know of at least 337 hot Jupiters to date, and have tried repeatedly to observe them at radio wavelengths. But “there have been no unambiguous [radio] detections” yet, Lingam says. Part of the problem, he explains, is that Earth’s ionosphere blocks radio waves from reaching the ground. To see radio waves produced by an exoplanet’s magnetic field, he says, “One would need to deploy large radio telescopes on the Moon or in outer space, both of which are expensive propositions.”

“We have the technology, but not the economics” to pursue exoplanetary magnetic field detections, he says.

But that may soon change. The proposed Farside Array for Radio Science Investigations of the Dark ages and Exoplanets, or FARSIDE telescope, is just one of several projects under consideration by NASA and other organizations for construction. And part of FARSIDE’s goal is right there in the name — it would focus on studying exoplanets and their magnetic fields to evaluate whether these distant worlds have magnetic fields that do indeed make them habitable.

Although researchers admit there’s still a long road ahead to gaining insight into exoplanetary magnetic fields — and thus, habitability — that road is getting shorter day by day.