Key Takeaways:

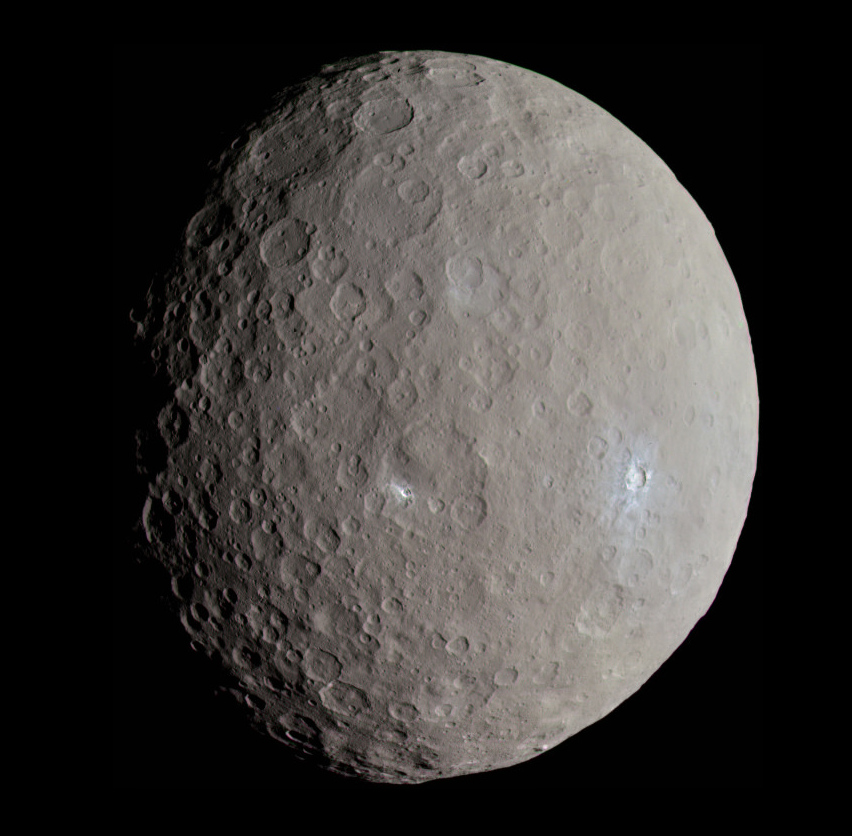

- Research by São Paulo State University (UNESP) has identified a population of "Venusian co-orbital asteroids" as a potential, currently undetectable, long-term threat to Earth.

- These asteroids orbit in 1:1 resonance with Venus, exhibiting unstable orbital configurations that, according to numerical simulations, could lead them to approach or cross Earth's orbit with a statistical probability of impact within millennia.

- Current observational methods are limited by solar brightness, resulting in a detection bias towards highly eccentric Venusian co-orbital asteroids, while a larger population with lower eccentricities remains hidden.

- Effective detection of these elusive objects, which pose a planetary defense concern, is challenged by the brief visibility windows from ground-based telescopes, necessitating future space-based missions like NASA's Neo Surveyor.

A possible threat to life on Earth has been identified by researchers at São Paulo State University (UNESP) in Brazil: asteroids that share Venus’s orbit but which currently can’t be detected. These objects haven’t been observed, but researchers want to expand the search for them. They say that some could strike Earth within a few thousand years.

“Our study shows that there’s a population of potentially dangerous asteroids that we can’t detect with current telescopes,” said astronomer Valerio Carruba, a professor at the UNESP School of Engineering at the Guaratinguetá campus and first author of the study in a statement. “These objects orbit the Sun, but aren’t part of the asteroid belt, located between Mars and Jupiter. Instead, they’re much closer, in resonance with Venus. But they’re so difficult to observe that they remain invisible, even though they may pose a real risk of collision with our planet in the distant future.”

An article on the subject was published by Carruba and colleagues in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics. The researchers used computermodeling and long-term numerical simulations to determine what kind of threat they posed to Earth.

Dubbed “Venusian co-orbital asteroids,” these rocky bodies orbit the Sun in the same region as Venus. They also revolve around our daytime star with similar periods. “These objects enter into 1:1 resonance with Venus, which means that they complete one revolution around the Sun in the same time as the planet,” said Carruba.

Jupiter has a similar group of asteroids, called Trojans, but their orbits are more stable. Even if they weren’t, the giant planet’s distance from us would keep them from being a threat. The Venusian co-orbitals, on the other hand, haveunstable orbits, and they switch orbital configurations about every 12,000 years. So, one of these asteroids can be close to Venus for a while but then pass close to Earth. “During these transition phases, the asteroids can reach extremely small distances from Earth’s orbit, potentially crossing it,” Carruba warns.

Related: Exploring Jupiter’s Trojan Asteroids

A lot more need to be found

As of this writing, astronomers have cataloged only 20 Venusian co-orbital asteroids. All but one of those have an eccentricity greater than 0.38 (where 0 would be a circular orbit). Their high eccentricities take them farther from the Sun, where telescope can discover them. But the computer models developed by the research team indicate many moreasteroids with lower eccentricities. And those wouldn’t be seen from our perspective on Earth. “The absence of objects with an eccentricity of less than 0.38 is clearly the result of an observational bias,” Carruba points out. In other words, those objects are hidden by the brightness of the Sun.

The group ran simulations showing that some of the objects could come dangerously close to Earth. The distances they got were so small that, statistically, they would correspond to impacts within a time frame of a thousand years.

“Asteroids about 1,000 feet (300 meters) in diameter, which could form craters 1.9 to 2.8 miles (3 to 4.5 kilometers)wide and release energy equivalent to hundreds of megatons, may be hidden in this population,” says Carruba. “An impact in a densely populated area would cause large-scale devastation.”

How to find them

Researchers calculated the odds of detecting these objects from Earth using the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope of the Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile. However, even the brightest asteroids would only be visible for perhaps two weeks if they were 20° or more above the horizon. “Such asteroids can remain invisible for months or years and appear for only a few days under very specific conditions. This makes them effectively undetectable with Vera Rubin’s regular programs,” Carruba said.

Another possibility involves using space telescopes like NASA’s Neo Surveyor, which the agency hopes to launch in late 2027. It could detect asteroids near Venus, providing more data on these elusive objects. “Planetary defense needs to consider not only what we can see, but also what we can’t yet see,” Carruba said.

Related: We’re coming for the asteroids. Are the asteroids coming for us?