Friday, November 5

The Moon reaches perigee, the closest point to Earth in its orbit around our planet, at 6:18 P.M. EDT. It will then sit 222,975 miles (358,843 km) away.

Fortunately for deep-sky observers, the Moon is also a tiny, 1-percent-lit crescent that sets shortly after the Sun, making tonight a great night for some fainter pursuits. Let’s try a famous one — the one, in fact, that “started it all” for Charles Messier, whose catalog of M-numbered objects we still use today as a guide for great targets.

M1, also known as the Crab Nebula, is a supernova remnant housing a rapidly spinning neutron star — called a pulsar — inside. Discovered in 1731 not by Messier, but by John Bevis, Messier spotted it independently nearly 30 years later, in 1758. Because he was searching for a comet — Halley’s Comet, actually, as it was predicted to return for the first time since its discovery — Messier marked down the position of the nebula to avoid confusing its fuzzy, circular glow with the comet. He continued doing so with many other faint, fuzzy objects, and today, we have the Messier catalog.

The Crab is roughly 6′ by 4′ across and located between the two horns of Taurus the Bull; it’s much closer to Alheka, the Bull’s right horn (if you picture his face looking toward us from the sky). M1 sits just 1.1° northwest of this 3rd-magnitude star. The nebula itself is magnitude 8, appearing as a faint, fuzzy splotch in most amateur scopes. You’re looking at the innards of a star whose explosion was recorded in A.D. 1054 by astronomers across the ancient world.

Sunrise: 7:34 A.M.

Sunset: 5:53 P.M.

Moonrise: 8:25 A.M.

Moonset: 6:35 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (1%)

*Times for sunrise, sunset, moonrise, and moonset are given in local time from 40° N 90° W. The Moon’s illumination is given at 12 P.M. local time from the same location.

Saturday, November 6

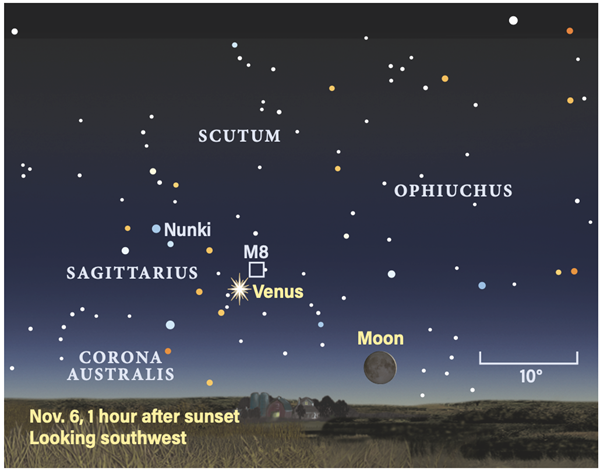

Venus crossed into Sagittarius November 1st and continues its trek through a rich region of the sky. Astroimagers take note: Tonight, the bright planet sits less than 3° south of the Lagoon Nebula (M8). This stunning star-forming region glows at magnitude 6 and stretches some 90′ by 40′. Embedded within it is a young cluster of stars: NGC 6530. These stars are a mere 2 million years old.

Through a telescope, you’ll see that Venus — blazing at magnitude –4.6 — is 28″ in diameter and 45 percent lit. A delicate crescent Moon, just 2 days old, sits about 18° to Venus’ west. Fortunately, its meager light won’t interfere with the scene once the sky grows darker.

If you are keen on photographing this meetup, take your time setting up your shot, getting the planet, the nebula, and the rich Milky Way in the frame. A great landscape in the foreground will only enhance the final image.

Sunrise: 7:35 A.M.

Sunset: 5:52 P.M.

Moonrise: 9:45 A.M.

Moonset: 7:20 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (5%)

Sunday, November 7

Daylight saving time ends this morning at 2 A.M. local time, when clocks across the U.S. will “fall back” by 1 hour.

Of course, an earlier sunset does have one advantage: more time in the evening to observe! Making a low arc in the southern sky this evening is the constellation Piscis Austrinus the Southern Fish. The most famous — and brightest — star in this small constellation is Fomalhaut, shining at magnitude 1.2. This star, which is only 25 light-years away, is the 18th-brightest star in the sky. Observations at infrared wavelengths show that it is surrounded by dusty disk that stretches to some 5 times the orbit of Pluto around our Sun. And more than 10 years ago, astronomers photographed what they believed was the first ever directly imaged exoplanet circling another star.

Called Fomalhaut b, researchers watched this distant world move over time as it circled its young star. But then something unexpected happened: In 2014, it disappeared. Astronomers now believe it was never a planet at all, but perhaps whatever remained following a collision of large, icy bodies in the disk.

The Moon passes 1.1° north of Venus at midnight EST tonight, although the two are well below the horizon by then. If you want to catch them, you’ll want to do so early in the evening — they set around 7 P.M. local time.

Sunrise: 7:37 A.M.

Sunset: 5:51 P.M.

Moonrise: 11:02 A.M.

Moonset: 8:13 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (12%)

Monday, November 8

Cassiopeia the Queen is easily recognizable in the northern sky, thanks to the W-shaped asterism formed by five of her stars. Tonight, swing your gaze in her direction to find NGC 663, an open cluster of stars also known as the Horseshoe Cluster.

Located about 1° southwest of the midpoint on a line drawn between Epsilon (ϵ) and Delta (δ) Cassiopeiae, NGC 663 contains about 400 stars and stretches 15′ across. If you’re viewing from an extremely dark spot after the Moon has set, you might see this cluster with the naked eye, but binoculars or a small telescope will easily pick it up from any location.

The cluster lies in a rich region of the sky, surrounded by numerous other clusters nearby. One is M103, another open cluster with about the same visual brightness but a much smaller, compact size of only 6′. Make sure not to confuse it with NGC 663, as the two look slightly similar. You’ll find M103 much closer to Delta Cas, about 1° northeast of the star — a little less than half as far as NGC 663 from Delta’s location.

Sunrise: 6:37 A.M.

Sunset: 4:50 P.M.

Moonrise: 11:11 A.M.

Moonset: 8:06 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (21%)

Tuesday, November 9

Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko is flying high right now in the constellation Gemini the Twins. Today, it’s less than 1.5° due south of bright 1st-magnutude Pollux, the constellation’s beta star and one of the Twins’ heads. You can catch the comet either late tonight before midnight, or early tomorrow morning before sunrise, thanks to the constellation’s current position in the sky.

Churyumov-Gerasimenko has a rubber duck-shaped nucleus that was studied up close by the Rosetta spacecraft several years ago. The comet has a period of 6.44 years and reached perihelion, the closest point to the Sun in its orbit, just one week ago. It has recently been recorded at magnitude 9.7 — fairly bright and not much dimmer than the famous Crab Nebula (M1) nearby in Taurus. If you’ve got good, dark skies, a 4-inch scope should net you both in the same field of view at low power. If you’re under light-polluted skies, you’ll want more aperture for a good view.

Also don’t be afraid to bump up the magnification and zoom in on the comet. Higher magnification will make it appear dimmer, but give your eyes some time and try tapping the scope — gently! — to make the small fuzzball pop out in your vision as your eyes’ motion-detector circuits kick in.

Sunrise: 6:38 A.M.

Sunset: 4:49 P.M.

Moonrise: 12:08 P.M.

Moonset: 9:25 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (31%)

Wednesday, November 10

If you’re up early — and up for a challenge — Mercury and Mars sit less than 1° apart this morning. To spot them, you’ll need a clear eastern horizon and an alarm set to alert you just before the Sun rises. At that time, put your binoculars or telescope away to avoid accidentally damaging your eyes.

The two planets are barely 4° high 30 minutes before sunrise. Mercury is brighter at magnitude –0.9, while the Red Planet is a fainter magnitude 1.6 — difficult to spot in the encroaching dawn without optical aid. Through a telescope, Mercury is 5″ wide and 94 percent lit, while Mars — physically larger but also more distant — stretches 4″ across.

The Moon passes 4° south of Saturn at 9 A.M. EST. This pair will be easier to catch, still fairly high in the south at sunset. The Moon will then be 6.2° southeast of the magnitude 0.6 planet, working its way toward Jupiter to the east. It will meet up with the solar system’s largest planet tomorrow.

Saturn looks stunning through a telescope, its rings stretching 38″ across. Those rings are currently tilted 19° to our line of sight, showing us their northern side. Once it’s fully dark, look also for Saturn’s brightest and largest moon, Titan. Tonight, it sits just less than 3′ due east of the ringed planet, glowing at magnitude 8.8. Even with the relatively bright crescent Moon nearby, you should be able to spot it. It’s headed toward the planet’s south and will sit due south of Saturn in just four days.

Sunrise: 6:40 A.M.

Sunset: 4:48 P.M.

Moonrise: 12:54 P.M.

Moonset: 10:36 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (42%)

Thursday, November 11

First Quarter Moon occurs at 7:46 A.M. EST. Our satellite then passes 4° south of Jupiter at noon EST. By sunset, the two are just over 5° apart, with Jupiter now slightly northwest of the Moon.

All four of Jupiter’s Galilean moons are on display early tonight, with Europa sitting alone to the planet’s east and Io (closest), Ganymede, and Callisto (farthest) stretching out to the west. But just wait — around 9:17 P.M. EST, Io disappears behind Jupiter’s large disk. Although it clears the disk less than two hours later, it won’t reappear until after the planet has set. That’s because Io also has to trek through Jupiter’s long, dark shadow, which stretches far east of the planet.

Fortunately, Jupiter has more to offer: Its Great Red Spot is on display tonight, rotating into view shortly after sunset and appearing about midway across the disk at 8:53 P.M. EST. Use the spot to track Jupiter’s fast rotation; the planet makes one full revolution in less than 10 hours.

Sunrise: 6:41 A.M.

Sunset: 4:47 P.M.

Moonrise: 1:32 P.M.

Moonset: 11:46 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (52%)

Friday, November 12

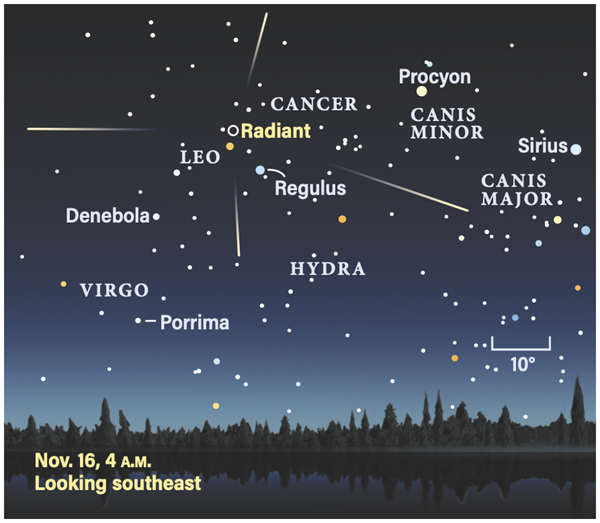

This month’s Leonid meteor shower peaks the 17th — which, unfortunately, closely coincides with the Full Moon. That makes this week your best bet at spotting shower meteors. This morning offers several hours of darkness, as the Moon sets late Thursday night, shortly before the calendar changes to Friday.

The Leonids’ radiant in near Adhafera in Leo the Lion is highest closer to sunrise, so try stepping outside a few hours before dawn to catch it at its best. Even at their peak, the Leonids will only produce about 10 meteors per hour, so while you should notice more meteors than the sporadic background rate of only a few per hour, don’t expect a stunning show. Still, it’s a great time to enjoy the early-morning autumn sky, which contains not only Leo but also Cancer, Orion, Gemini, Taurus and Perseus. There’s a plethora of familiar constellations and easy-to-find deep-sky objects, including the Pleiades, the Crab Nebula (M1), the Orion Nebula (M42), and the Perseus Double Cluster.

Sunrise: 6:42 A.M.

Sunset: 4:46 P.M.

Moonrise: 2:02 P.M.

Moonset: —

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (63%)