Editor’s note: Jupiter’s opposition occurred on Monday (Sept. 26) at 4 P.M. EDT. However, if you plan to observe the gas giant, it will continue to be near its finest for the next few weeks.

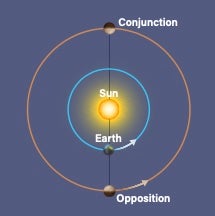

In 2022, Jupiter reaches opposition — the point in its orbit opposite the Sun as seen from Earth — on Sept. 26. It’s also the giant planet’s closest approach to Earth since October 1963. On the 26th, Jupiter will blaze at magnitude –2.9, making it the brightest starlike object until Venus rises shortly before sunrise.

If you can’t observe Jupiter exactly at opposition because of a personal commitment or clouds, don’t fret. You’ll have plenty of time to see the king of the planets while it’s big and bright: At no time from July 20 through Dec. 3 does its magnitude dip below –2.6.

On its opposition date, Jupiter sports an apparent diameter of 49.9″, which is quite close to its greatest possible size of 50.1″. And between the two dates above, its apparent size is at least 43″. So, now is the time to set up your telescope, crank up the power, and observe Jupiter and its moons in all their glory.

Moving right along

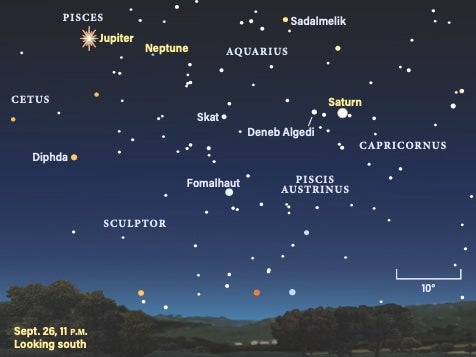

Jupiter first entered Pisces in mid-April; then, from late June until early September, it crossed in front of some stars in the northwestern corner of the constellation Cetus the Whale before returning to Pisces. This whole region lacks any bright stars, so it will provide a huge contrast to Jupiter’s brilliance. In fact, the nearest 1st-magnitude star, Fomalhaut (Alpha [α] Piscis Austrini), lies nearly 35° away.

For amateur astronomers in mid-northern latitudes, the planet’s location in Pisces means it will climb around halfway up the sky — not terrible, but still some distance from where you’d get the best views. For anyone at latitude 40° north on the date of opposition, Jupiter’s altitude at local midnight will be 50° above the southern horizon. In the Northern Hemisphere, for each degree of latitude south of 40° north an observer is, Jupiter will appear 1° higher; for each degree north of 40°, it will be 1° lower.

Crank up the power

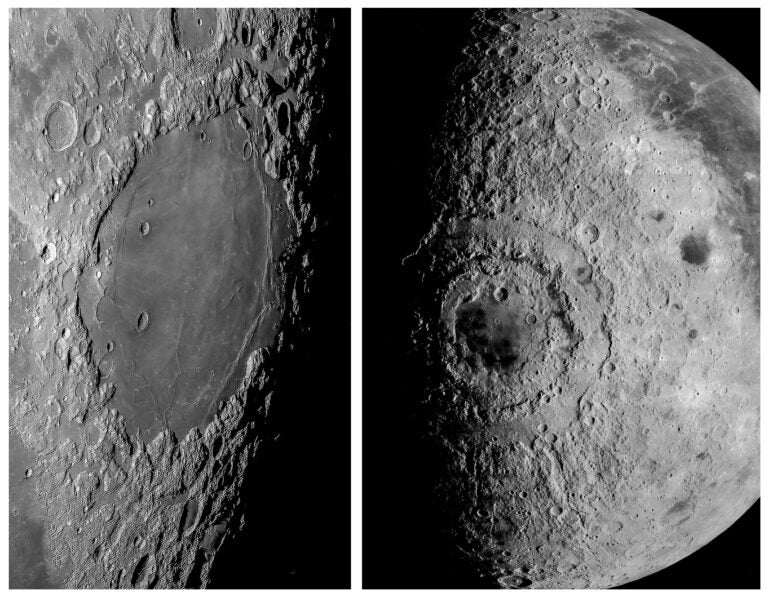

Through a telescope, Jupiter shows more detail than any other celestial object except the Moon. Even a 2-inch scope will show the planet’s four largest moons. The moons look like bright stars flanking Jupiter and can form some unusual arrangements.

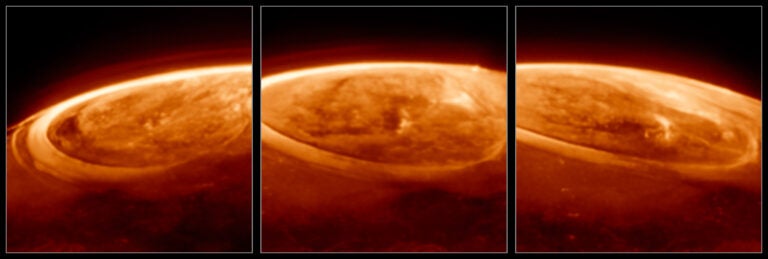

When you turn your gaze back to the planet, insert an eyepiece that provides a magnification around 100x, and the first details you’ll notice will be a pair of dark stripes oriented parallel to the planet’s equator. These stripes — one above and one below Jupiter’s equator — are the North and South Equatorial Belts. Through larger telescopes and with higher magnifications, more belts and zones come into view. Planetary observers call the light-colored bands zones and the darker ones belts.

At magnifications above 250x, Jupiter appears squished, bulging at its sides. That’s not an illusion. The planet’s rapid rotation and the fact that it is not solid make its equatorial diameter 5,800 miles (9,300 kilometers) greater than its polar diameter.

Rather than taking a quick look every now and then, try observing Jupiter over a series of nights. In addition to the changing positions of its moons, the planet’s period of nine hours and 551/2 minutes brings all of its visible area into view during a single night. Long-term observations may reveal individual features becoming more or less prominent and even disappearing for long stretches of time.

Spot the Spot

Jupiter’s most famous atmospheric feature is the Great Red Spot (GRS), a high-pressure storm that lies 22° south of Jupiter’s equator, drifting slowly through the South Equatorial Belt. You’ll spot other similar features, but most are white and none are as large. The GRS has a north-south width of 8,700 miles (14,000 km) and a variable east-west width that was measured at some 25,000 miles (40,000 km) in the 1890s. The storm is slowly shrinking, however, and is currently just 10,000 miles (16,000 km) across.

It also changes color because clouds at higher levels and of different compositions condense above it. The GRS has varied from brick red during the 1960s to pale pink in the 1990s. Since 2000, the spot’s hue has remained light orange.

Moving moons

Jupiter’s four largest moons are known as the Galilean satellites, named for their discoverer, Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei. On Jan. 7, 1610, Galileo saw three stars in a straight line, two on one side of Jupiter and one on the other. The next night, their positions had changed. Five nights later, he spotted a fourth star.

Galileo concluded that the “stars” were actually bodies revolving around Jupiter like the Moon circles Earth. His discovery made Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto the first objects in the solar system to be observed despite being invisible to the naked eye.

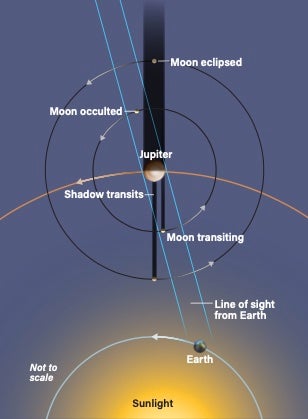

The ever-changing configuration of these moons can lead to four different types of observational events.

An eclipse occurs when a satellite moves through Jupiter’s shadow, but is not positioned behind the planet from our point of view.

An occultation happens when a satellite passes behind Jupiter. These events occur along the planet’s limb (edge). Eclipse events are easier to observe than occultations because eclipses usually take place some distance from Jupiter’s limb. Moons always disappear into occultation at the west side of Jupiter and reappear at the planet’s east side.

A transit occurs when a moon moves in front of the planet. A transiting satellite always moves from east to west across Jupiter’s face. The satellites themselves look like bright dots against Jupiter’s dark belts. When a satellite lies in front of the brighter zones, however, it’s hard to see unless you follow it from the time the transit starts.

A shadow transit happens when a moon’s shadow moves across Jupiter’s disk. Shadows of the moons look like small black dots on Jupiter through any telescope. Transiting shadows also move from east to west across Jupiter.

Before opposition, from our perspective on Earth, Jupiter’s shadow extends west of the planet, so a satellite will be eclipsed before it’s occulted. The satellite being eclipsed gradually fades as it enters Jupiter’s shadow, which is pretty cool to watch.

The two outer satellites, Ganymede and Callisto, are usually far enough from Jupiter to reappear from an eclipse, so you’ll be able to see them disappear into occultation. However, Io and Europa emerge from their eclipses after their occultations start, so you won’t see them reappear — they’ll be behind the planet.

After opposition, when Jupiter’s shadow falls east of the planet, occultations occur before eclipses. Then, you’ll be able to see Io and Europa disappear into occultation and reappear from eclipse.

For transits and shadow transits before opposition, the satellite’s shadow falls on the planet before the transit starts. After opposition, this order is reversed: The satellite begins its transit and the shadow follows.

Please note that any of these events can occur simultaneously among the four moons. For example, you might observe one or more satellites in transit across Jupiter, concurrent shadow transits, or multiple moons occulted by the planet.

If you have a 10-inch or larger scope and a night with great sky conditions, look for details on the moons. With high magnification (above 350x), you’ll resolve their disks, especially during transits when the moons’ glare drops because Jupiter’s lit background provides less of a contrast than the black sky. Zoom in on Ganymede, the largest moon, first. Look for light-colored ice near its poles. Through bigger scopes, you might be able to see each satellite’s (extremely) subtle color.

Less light, better view

The best advice I have for Jupiter observers is to use color filters to bring out details you won’t see otherwise. And although they’re called “color” filters, they produce non-color (grayscale) views. Their purpose is to enhance the contrast between features that are next to one another. Astronomical filters screw into the bottoms of eyepieces, which have matching threads. Like eyepieces, they come in two sizes, 11/4″ and 2″.

Manufacturers label filters by color and number. For better views of Jupiter’s dark reddish-brown belts than you’d normally get, use a green (No. 58) or blue (No. 38A) filter. Blue also works best to sharpen any bright cloud features. A yellow (No. 12) filter will darken the planet’s bluish features such as festoons, small regions that appear from time to time near the planet’s equator.

Most observers use red (No. 23 or No. 25A) filters to enhance white spots and ovals in the South Temperate Belt and South Temperate Zone. Red filters also seem to work well on boosting the contrast of the northern and southern borders of the major belts.

Remember, filters don’t make features brighter. Quite the opposite. So, when you use them you’ll get better results through larger telescopes with eyepieces that provide medium to high magnifications. If you have a 6-inch or smaller telescope, use lighter filters. For example, use light red (No. 23A), light yellow (No. 8), or light blue (No. 82A) filters rather than their darker counterparts.

An audience with the king

As summer transforms to fall in the Northern Hemisphere, Jupiter provides a brilliant target for any observer, no matter your equipment. It’s so bright, in fact, that you won’t need to head to a dark site to view it. Set your scope up in your yard, pull up a chair, and carve out some time to see the giant planet at its best.

Jovian fun facts

• Jupiter’s magnetosphere is the largest structure in the solar system. If it were visible from Earth, it would appear larger than the Full Moon.

• On a moonless night at a dark site, Jupiter can cast a visible shadow.

• At its equator, Jupiter rotates at 28,100 mph (45,300 km/h), more than 27 times as fast as Earth.

• If Jupiter were hollow, it could hold 1,320 Earths.

• On average, Jupiter travels 5′ per day against the background stars. So, in a little over six days, the giant planet moves roughly the width of the Full Moon.

• The King of Planets is almost 318 times as massive as Earth.

• Jupiter reflects 34 percent of the sunlight that falls on it.

• The brightest planetary satellite visible from Earth (not counting the Moon) is Ganymede. At opposition, the solar system’s largest moon glows at magnitude 4.4, a brightness that would make it visible to the naked eye if the glare from Jupiter didn’t overwhelm it.