Most readers of Astronomy who observe the sky have either owned or viewed through Celestron equipment. So, we thought it fitting to take a look at the history of this important company and perhaps glimpse what the future may hold.

The 1950s and ’60s

American electronic engineer Tom Johnson founded the parent company of Celestron, Valor Electronics, in 1955 in Gardena, California. The company produced components for both industry and the military.

A few years later, Johnson was searching for a telescope for his two young sons. When he didn’t find one that he thought was good enough, he built a 6-inch reflector. The project got him interested in constructing telescopes, so he began building larger and more complex instruments. Believing that his hobby could grow into a full-time business, he created an astro-optical division within Valor Electronics in 1960.

On July 28, 1962, Johnson brought a portable 18¾-inch Cassegrain reflector to a star party hosted by the Los Angeles Astronomical Society on the summit of Mount Pinos, in the Los Padres National Forest. He had built the scope from surplus parts in six months, and for only $1,000. Attendees loved his telescope and many asked him if he would build more.

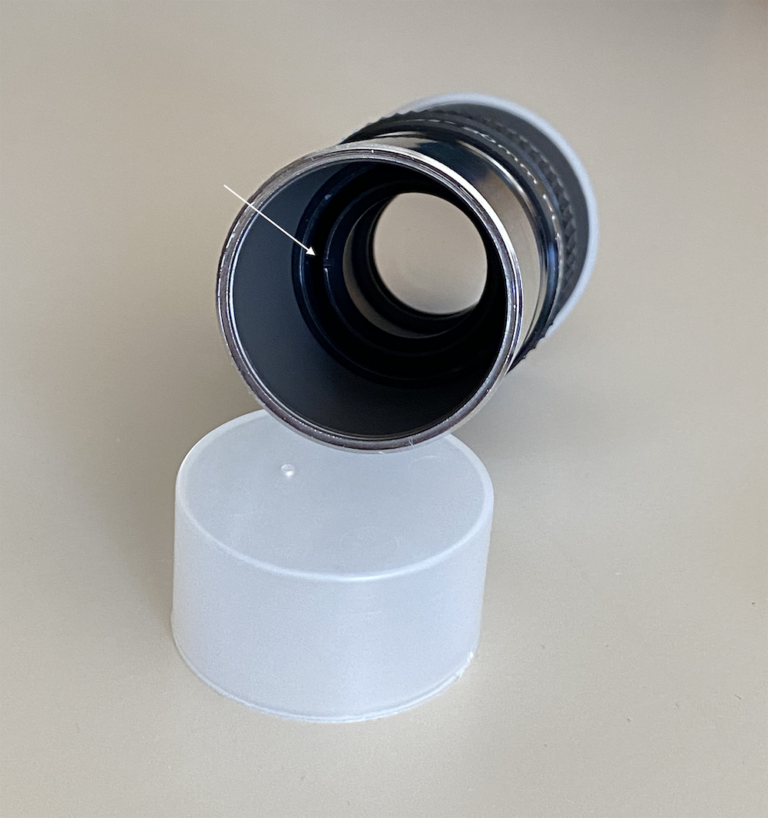

Rather than duplicate his telescope, Johnson created a Schmidt-Cassegrain (SCT) design, which incorporates features of a refractor and a reflector. He then invented a method to produce it in quantity.

Johnson’s biggest challenge was making the glass corrector plate, the SCT’s front optic. This thin piece of glass contains a subtle curve, allowing it to “correct” the errors introduced by the spherical mirror the scope uses, and, at first, it was difficult for Johnson to create them in quantity.

Once that hurdle had been overcome, his 20-inch SCT, the Celestronic 20 (C20), was ready for sale. In May 1964, the new company he created, Celestron Pacific (a division of Valor Electronics), advertised C20s for sale.

In December of the same year, Johnson changed Valor Electronics’ name to Celestron Pacific. Later, he dropped “Pacific,” and Celestron was born. By 1969, the company was advertising a full line of SCTs: the C6, C8, C10, C12, C16, and C22.

The 1970s

By 1970, designers and engineers Johnson had hired discovered ways to manufacture SCTs in volume and at reasonable cost. Their first product was the famous 8-inch Celestron C8, an f/10 SCT that sported a bright orange tube. This product revolutionized the amateur telescope market because its price tag was less than $1,000.

That same year, Celestron also offered the C10, C12, C16, and C22 for observatories. Each of these models came with a pier rather than a tripod.

The popularity of the C8 among visual observers and an ever-growing number of astrophotographers led to the company introducing a 5-inch SCT, the C5, in 1971. Also in that year, Celestron created its Cold Camera. This device chilled the 35mm film strip within it, dramatically reducing exposure times.

In 1972, Celestron added a 14-inch model, the C14. For several decades it was the world’s largest production catadioptric telescope. Around this time, Johnson began to take a less active role in the company. In 1973, Alan Hale succeeded Johnson as president. Hale later became CEO in 1978.

Before coming to the company in 1960, Hale had no technical experience. “I was just a young kid who graduated from high school the year before,” he says. “I was going to college and working part-time jobs to support myself. I still wasn’t sure what I wanted to be when I grew up.”

But Hale learned quickly and helped the company flourish as he moved up through the ranks.

The 1980s

In 1980, Johnson and Hale sold Celestron to Diethelm Keller Holding, a large manufacturing company in Zurich, Switzerland. After the sale was complete, Johnson retired. Hale remained for a time, but later left. He returned in 1987 to turn Celestron around after it nearly collapsed following the appearance of Halley’s Comet.

“All companies sold whatever they could get their hands on during the comet hoopla,” Hale says. “However, Celestron was not managed well at the time. The senior management believed sales would keep rising even after the comet, but this was a really stupid mistake. That group did a bad job at virtually everything.”

But Hale believed the troubled company could be successful again. “Our parent company in Switzerland was very supportive,” he says. “Still, I had to invest money of my own, and everything was at risk.” Hale said that he felt a great sense of satisfaction from seeing employees, suppliers, and retailers pulling together to put Celestron back on solid footing.

The company’s major technical milestone in the 1980s was the introduction of the first mass-produced, fully integrated computerized go-to telescope, the CompuStar 14. The scope’s drive, which was controlled by an Intel 8052 microprocessor, contained a database of more than 8,000 celestial objects. With this instrument, amateur astronomers could spend less time searching for targets and more time observing them.

The 1990s and 2000s

In 1992, Celestron freed itself from the bonds of Earth as a C5 and an 8×50 Polaris finder scope were flown aboard space shuttle Atlantis. Later that year, Atlantis carried a C8 into space.

The mid-1990s saw Celestron take a major step toward the realm of portable observing. In 1996, the company introduced the Ultima 2000, the first go-to scope that ran on AA batteries. This advance allowed viewing in remote locations without observers worrying if they’d run down their car batteries.

Joe Lupica was a key figure during the ’90s. He had joined the senior management team in June 1987. Lupica had a strong financial background, having been chief financial officer of an independent oil and gas exploration company, where he’d assisted in the syndication of 25 limited partnerships.

Lupica became Celestron’s CEO in 1996. Starting in 1998, he led the company through four turbulent years when Tasco, then of Miramar, Florida, owned it. Tasco had purchased Celestron from Diethelm Keller Holding. On June 28, 2002, Lupica, Hale, and Senior Vice President Rick Hedrick (currently the CEO of PlaneWave Instruments) purchased Celestron from Tasco. Following the purchase, the company developed many new products and became financially stronger than it had ever been.

In 2005, Lupica and his partners sold the company to a group of investors led by David Shen, the owner of Synta Technology Corporation in China. Lupica stayed with Celestron after the sale, helping to develop products with more features at lower prices.

In 2006, the company veered a bit from telescopes when it unveiled the SkyScout Personal Planetarium. This handheld device used GPS technology to identify thousands of stars, constellations, and planets with the click of a button. And Celestron ended the ’00s with a bang when it introduced the EdgeHD line of telescopes, which incorporates an aplanatic flat-field Schmidt optical system. This virtually eliminated the aberrations of field curvature and coma, producing pinpoint stars to the edge of the field of view of even the largest imaging sensors and wide-field eyepieces.

2010 to now

In the 21st century’s second decade, Celestron has continued to introduce great products. In 2011, its StarSense Technology made setup nearly hands-free. Using an internal camera and software, the SkyProdigy telescope line, which used StarSense, could align itself in less than three minutes. And two years later, the company announced the StarSense AutoAlign accessory, which attaches to any Celestron scope for a three-minute alignment.

Lupica announced his retirement in 2013 at the “Perspective on Imaging” meeting hosted by Celestron. This one-time gathering was a first in the telescope industry and featured Astronomy’s editor, David J. Eicher, and the author as guest speakers. “It is difficult to identify one moment in 26 years as my proudest,” Lupica says, reflecting on his time with the company. “Over the last four years of my career, Celestron achieved the highest sales ever in its 52-year history. In fact, net earnings during that four-year period exceeded the total net earnings of the company over the previous 48 years.

“That being said, I think I am most proud of the team I assembled at Celestron that achieved these goals and the company culture we established during this period of time. I developed a close relationship with 50 to 75 team members,” Lupica says, “and that has made retiring very difficult. But at the same time, I am proud that this team will be able to carry on successfully for many years in the future.”

In 2013, Dave Anderson succeeded Lupica as Celestron’s CEO. He had worked at Celestron for 16 years, holding multiple positions in finance and operations.

Anderson’s philosophy on growth and outreach for the company at this time was simple: “The greatest opportunity is with the youth,” he says. “Technology is being introduced at earlier periods of a child’s development. Though there may be many benefits, I also believe that this encroachment may begin to limit exploration.” He accurately foresaw hands-on experiences giving way to virtual ones. Since Anderson’s tenure as CEO, getting high-quality products into the hands of youth has been a constant topic at Celestron. Employees believe telescopes are the tools that can ignite the passion not just for space, but for science in general.

One example is the company’s NexStar Evolution, which came out in 2014. It introduced Wi-Fi technology to the NexStar 6-, 8-, and 9.25-inch SCTs. Users just needed to download Celestron’s SkyPortal mobile app.

The same year, two optical engineers — Dave Rowe and Mark Ackermann — teamed up with Celestron to develop another new product. The Rowe-Ackermann Schmidt Astrograph (RASA) is an imaging scope with a native f/2.2 focal ratio. The RASA is available in 8- and 11-inch, as well as 36-centimeter (14-inch), versions.

In January 2017, Corey Lee became Celestron’s CEO when Anderson, who continues to assist Celestron in a consultant role, resigned. “It has been a privilege to guide the amazing talent that comprises Celestron,” Anderson said. “I’m committed to supporting a smooth and seamless transition of leadership.”

Lee began his career with Celestron in 1995 as an engineer and, over time, held roles with increasing responsibilities within the company. Lee joined the company’s executive team in 2006, and most recently served as executive vice president of marketing, sales and product development. He’s also been involved with the amateur astronomy industry for more than 20 years.

His guidance as CEO has helped Celestron build a strong leadership team. He also led the team that developed numerous impactful products, including the highly regarded EdgeHD optical system. And he set the course for the development of StarSense, the company’s fully automated telescope alignment technology.

StarSense Explorer technology figures into Celestron’s latest product, the NexStar Evolution 8 HD Telescope with StarSense. And the company has produced a 60th Anniversary Edition of the telescope.

This is the world’s first consumer telescope to affordably offer sky-recognition technology used by professional observatories. By utilizing existing smartphone camera hardware, it can quickly determine the position of the telescope. Once that’s done, it compares the section of sky the scope is pointed at, and guides users to thousands of celestial objects.

To use it, the user just places an Android or iOS smartphone in the dock on the scope and launches the included app. The app allows users to follow on-screen arrows to locate a desired object without a Wi-Fi or cellular signal.

“StarSense Explorer finally offers consumers who were daunted by telescopes an accessible path to sky exploration that is easy, affordable, and visually breathtaking,” Lee says.

Bright future

“I look forward to working closely with our talented team of individuals to continue Celestron’s long tradition of creating innovative products that inspire a sense of wonder and also make it easier for all to discover science and nature,” Lee says. “I have a tremendous amount of passion for this industry and will work hard to continue to grow the hobby of astronomy and maintain Celestron’s position as the industry leader.”

It’s this positive attitude that has characterized Celestron since Johnson designed his first telescope. And it’s clear that Celestron will remain at the forefront of our hobby for a long time to come.