Key Takeaways:

October’s longer nights bring two transits of Titan across Saturn, while Io and Europa tango together across Jupiter three times. Mercury and Mars make a brief evening appearance, and Venus dominates the morning sky. Plus, the fine Orionid meteor shower occurs during the dark of the Moon.

Mercury and Mars meet in the evening sky, although their low altitude means Northern Hemisphere observers will find them difficult to spot. They reach conjunction less than 2° apart on Oct. 19. Both set less than an hour after sunset.

On the 19th, look for magnitude –0.2 Mercury 4° high in the southwest 20 minutes after sunset. You might spot it with binoculars. Within 10 minutes it drops below 3° in altitude. From Mercury, scan 2° to the upper right to try spotting dimmer Mars at magnitude 1.5.

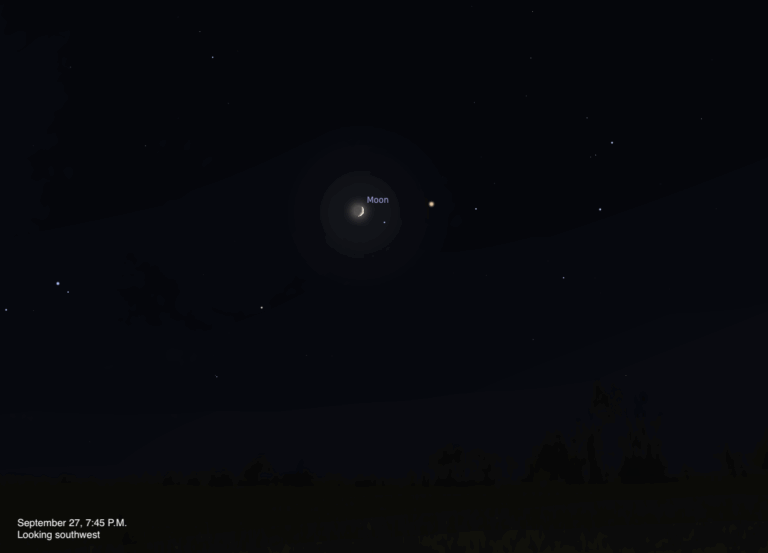

Mars is quickly heading toward solar conjunction. Mercury stands between the Red Planet and a crescent Moon Oct. 23. Mercury is 4.5° northwest of the Moon; they are very low in the southwest and set by 7 p.m. At about 6:40 p.m. local daylight time in North America, they stand 2° to 3° high. Can you also spot magnitude 1.1 Antares, 9° high and almost 13° east of the crescent Moon in the twilight?

Mercury reaches greatest eastern elongation Oct. 29, when it is 24° from the Sun. Its low declination limits its visibility after sunset. By Oct. 30 Mercury has crossed into Scorpius and is less than 9° west of Antares. Half an hour after sunset, Mercury is 3.5° high. It sets by 7 p.m. local daylight time.

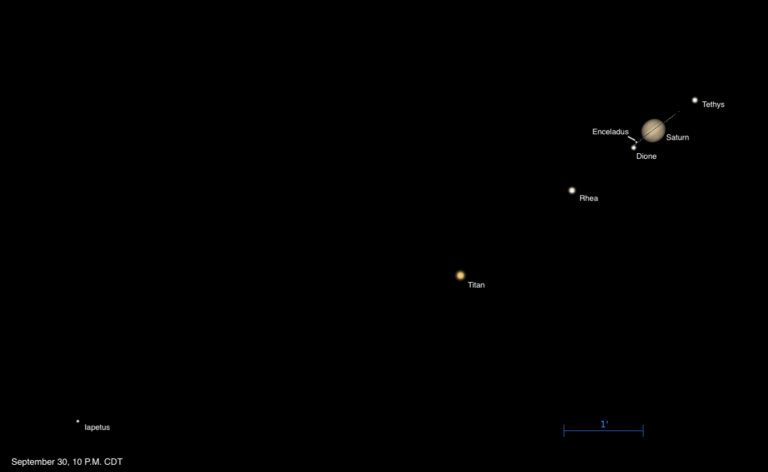

Saturn is in the northeastern corner of Aquarius and just over a week past opposition when the month begins. It stands high in the eastern sky after dark and remains visible all night. Saturn is 4° south of the nearly Full Moon on Oct. 5.

Saturn maintains its opposition magnitude of 0.6 for the first week of October and dips to 0.8 by the end of the month, when it stands 816.2 million miles away. A telescope will show a 19″-wide disk. Inspect both hemispheres while the rings are almost edge-on. Look for new white spots that signify storms welling up above the normally yellowish hazy layers.

This month the rings’ tilt declines from 1.5° to 0.6°. They appear only 0.5″ thick, requiring larger amateur scopes and good seeing to spot. The long axis spans 43″ midmonth.

Two transits of Titan — one with its shadow — occur in October. On Oct. 5, Titan’s transit begins around 9:25 p.m. EDT (in twilight for the Mountain time zone). It takes about 18 minutes for Titan to fully appear on Saturn’s northeastern limb. Shortly after the moon reaches halfway across around 12 a.m. EDT (Oct. 6 in the Eastern time zone), its shadow appears at 12:26 a.m. EDT, crossing the north pole of the planet. The shadow is halfway across at about 1:38 a.m. EDT and leaves the disk from about 2:17 a.m. to 2:42 a.m. EDT. The shallow angle of the limb makes egress very long. Titan reaches the limb at 2:23 a.m. EDT and exits by 2:44 a.m. EDT.

The second event occurs Oct. 21. The initial stages are best viewed from the Central time zone eastward — the transit is underway as Saturn rises in the Mountain and Pacific time zones. Titan begins ingress at 6:42 p.m. EDT. It takes three hours to reach the midpoint of Saturn’s disk. Titan reaches the northwestern limb at 12:22 a.m. EDT (now the 22nd in the Eastern time zone) and is clear of the disk by 12:41 a.m. EDT.

Orbiting closer to Saturn, Tethys, Dione, and Rhea shine at 10th magnitude. Twelfth-magnitude Enceladus is more difficult to spot, orbiting just outside the edge of the rings. It’s a great time to try viewing this faint moon without the brilliance of the rings interfering.

On Oct. 7, two-toned Iapetus reaches eastern elongation 9.5′ east of Saturn. It’s always dimmer at eastern elongation and shines around magnitude 12. For the first two weeks of October it remains near this location. By the third week, Iapetus moves toward inferior conjunction, which occurs the evening of the 26th, when it’s 1.3′ due north of Saturn. Now 11th magnitude, it should be easy to spot through a telescope.

If you center Saturn in 7×50 binoculars, Neptune lies at the outer edge of the field of view, 3° northeast of Saturn on the 1st. Saturn’s motion westward increases this gap to 4° by the end of October.

Neptune is just past opposition and visible all night, reaching its highest point in the south around local midnight. It is magnitude 7.7, within range of binoculars. Numerous 6th-magnitude stars in the same field aid in identification of the distant planet. Just east of Saturn’s location is a group of four stars forming a parallelogram (these are 27, 29, 30, and 33 Piscium). Neptune stands about 1.7° north of the northeasternmost star (29 Psc).

Neptune lies 2.7 billion miles from Earth and spans a mere 2″, but is clearly non-stellar through a telescope. It reveals a bluish hue.

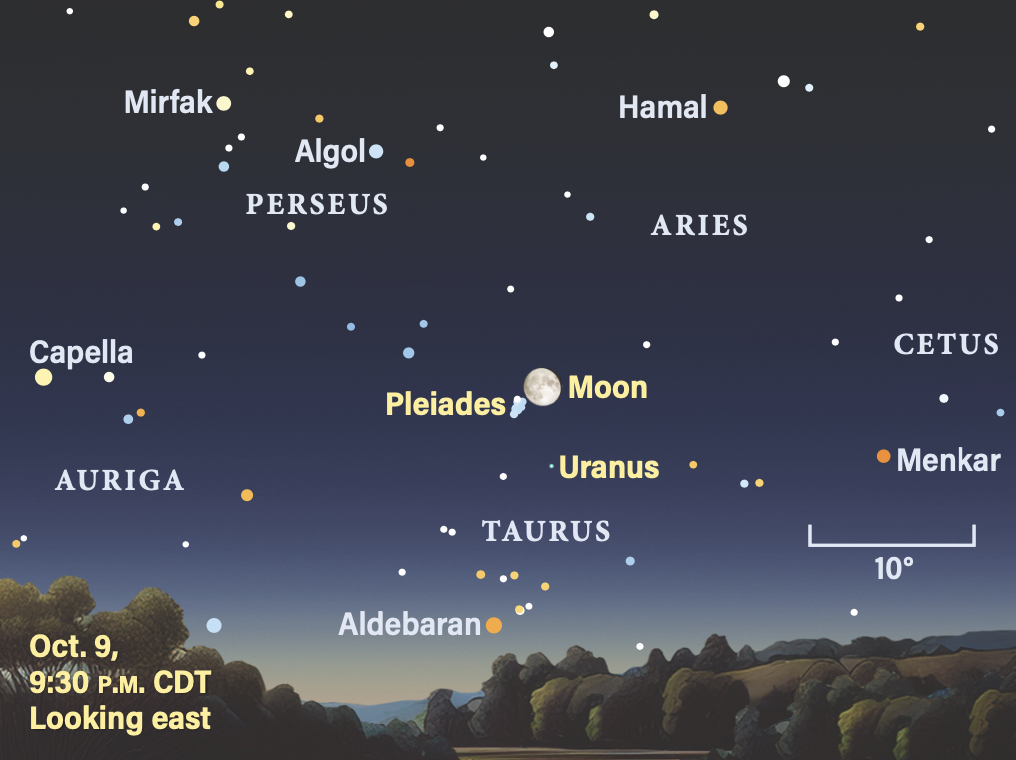

Uranus is one month from opposition and rises two hours after sunset. It’s best viewed after midnight, when it is over 40° high in the east in the constellation Taurus. It’s easy to find just over 4° south-southeast of M45, the Pleiades. You’ll want binoculars or telescope to spot the magnitude 5.6 planet.

Uranus moves about 1° west during the month. A pair of 6th-magnitude stars (13 and 14 Tauri) standing 20′ apart lie 4.5° south of M45, and Uranus is 3° to 2° east of this pair during the month. The pale green, 4″-wide planetary disk is visible using medium to high magnification through a telescope.

A waning gibbous Moon stands 4.7° north of Uranus Oct. 9/10 and crosses the Pleiades, producing a series of occultations. The stars disappear behind the Moon’s bright limb, making those events difficult to observe, but reappearances at the dark limb are easier to see. Electra is the first bright star to be occulted from most of North America. The timing will vary with your geographic location. Observing between 11 p.m. and 1 a.m. EDT will offer the best views (starting on the 9th and ending early on the 10th for those in the eastern half of the U.S.). Check which events are visible from your location under “2025 Predictions” at www.lunar-occultations.com/iota/iotandx.htm.

Jupiter rises around 12:30 a.m. local daylight time Oct. 1 and shines at magnitude –2.1. In the hour before dawn, the giant planet stands more than 50° high, a great time to view it. By the end of October it is up well before midnight. It lies southeast of the stars Castor and Pollux in Gemini. A waning Last Quarter Moon hangs above Jupiter the morning of Oct. 13.

Jupiter is a delight through any telescope. Immediately obvious are twin dark belts straddling the equator. Finer details in its dynamic atmosphere are readily seen with patience, letting your eye relax into the view over minutes.

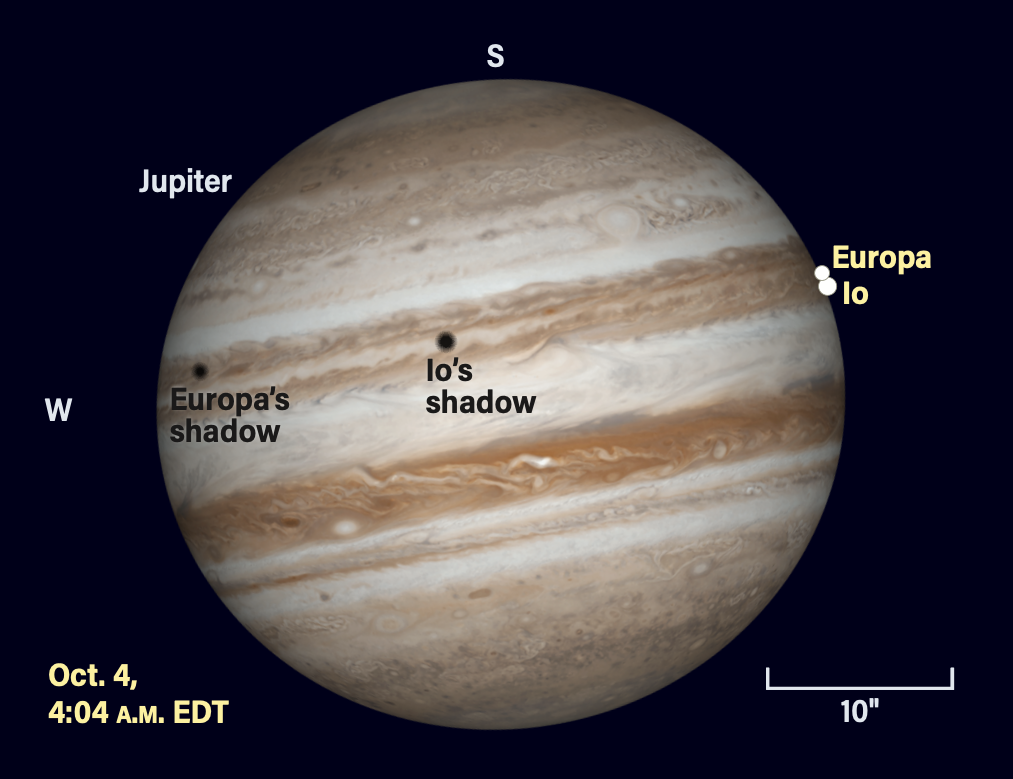

Jupiter’s bright Galilean moons orbit every two to 17 days. There are many transits, occultations, and eclipses, but here’s a special sequence: On Oct. 4, a rare event occurs when Io and Europa cross the disk together, partially overlapping as they begin a transit. Both their shadows are already on the disk, well separated. This fascinating juxtaposition begins at 4:04 a.m. EDT as both moons cross onto the southeastern limb of Jupiter. Io’s shadow is in the middle of the disk, with Europa’s nearing the western limb. Europa’s shadow leaves the limb at 4:17 a.m. EDT.

As Io’s shadow reaches the western limb at 5:03 a.m. EDT, Io has pulled ahead of Europa and is in the middle of the disk, while Europa lags behind due to its wider orbit. Seeing orbital mechanics at work in one session is rare, so don’t miss this.

Because Io and Europa are in resonant orbits, similar events occur repeatedly. On Oct. 11, both shadows appear by 4:43 a.m. EDT, with the moons situated off the eastern limb. Io is well ahead of Europa, but its shadow lags behind Europa’s. Io reaches the limb at 5:58 a.m. EDT, as its shadow is catching up to Europa’s. Europa begins its transit at 6:43 a.m. EDT, just as the shadows almost merge and leave the western limb of the planet 10 minutes later and three minutes apart.

The series repeats Oct. 18. This time both shadows begin a transit within six minutes of each other, with Io’s shadow leading at 6:36 a.m. EDT. Io’s transit starts at 6:52 a.m. CDT, as twilight begins across the Midwest. Western states see the later stages. Europa begins its transit 87 minutes later at 6:19 a.m. PDT, coincidentally shortly after Callisto’s shadow begins to transit at the southeastern limb (at 6:07 a.m. PDT).

Pacific Coast observers will see the pair of shadows at the onset of morning twilight Oct. 25, the last in this series for the month.

Venus rises at 5 a.m. local daylight time on Oct. 1, shining at magnitude –3.9 among the stars of Leo. It crosses into Virgo by the 9th and its elongation from the Sun is declining, so it rises later each morning. It’s joined by the waning crescent Moon on the 19th; the pair rises around 5:30 a.m. across North America. They stand less than 4° apart, with the Moon just two days from New. Through a telescope, Venus displays a 94-percent-lit disk spanning 11″.

By the end of October, the phase expands to 96 percent and the disk shrinks to 10″. On the 31st Venus stands 4° north of Spica, although the magnitude 1.0 star is difficult to see in the brightening sky.

Rising Moon: Old and young

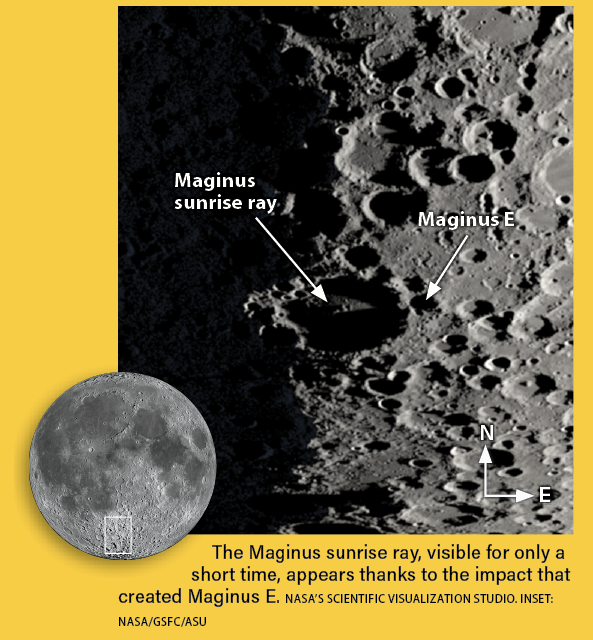

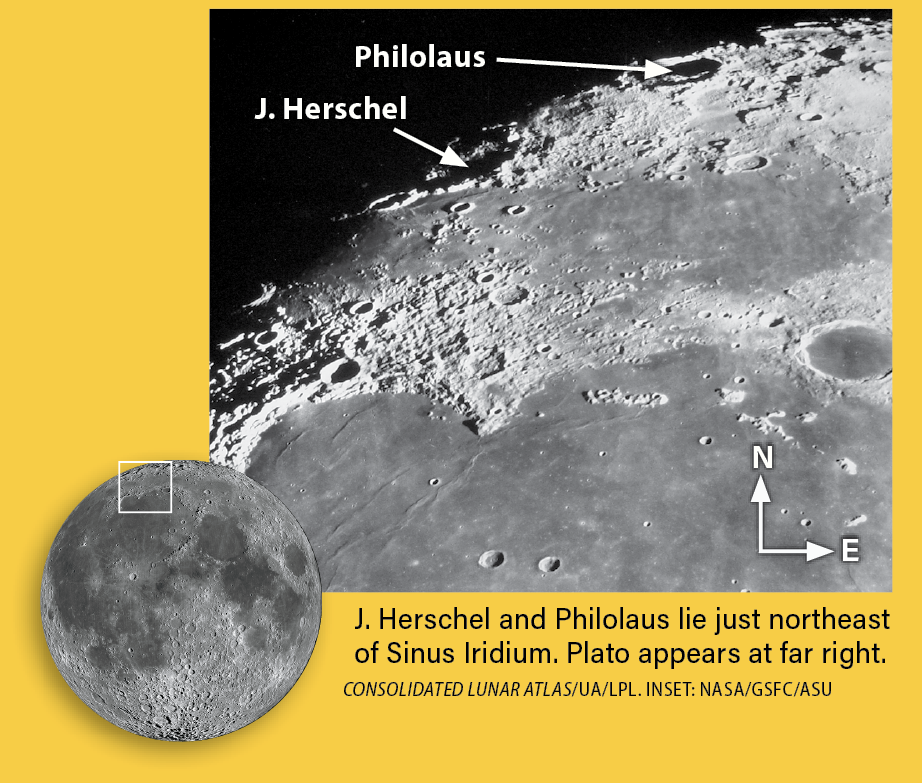

There is some lunar eye candy on the evening of the 2nd. In the south lie the elongated Schiller and the detail-packed Gassendi; the equator sports the small and sharp Kepler, leading north to the outstanding half-ring of the Jura Mountains. Keep going north for some lunar history.

The large crater J. Herschel spans 96 miles and betrays its age in two ways. First, the poor rim has been long battered down by smaller impacts and has so many dents that the low-angle sunlight easily streams into the middle. And second, what would have been a complex jumble of central peaks lies buried under the immense amount of rubble thrown out by the giant impact that carved out the Imbrium basin. It looks like someone has kicked dirt on a key lime pie.

Closer to the pole, the 44-mile-wide Philolaus has much younger features, most notably a sharp and tall rim that casts a long, dark shadow. Return for the next night or two to see its twin central peaks. Herschel may be unrecognizable by now. (Philolaus was a 5th-century Greek who followed Pythagoras and said that Earth was moving. John Herschel charted the southern sky.)

You can try again on Nov. 1st, with lighting 10 hours later than pictured here.

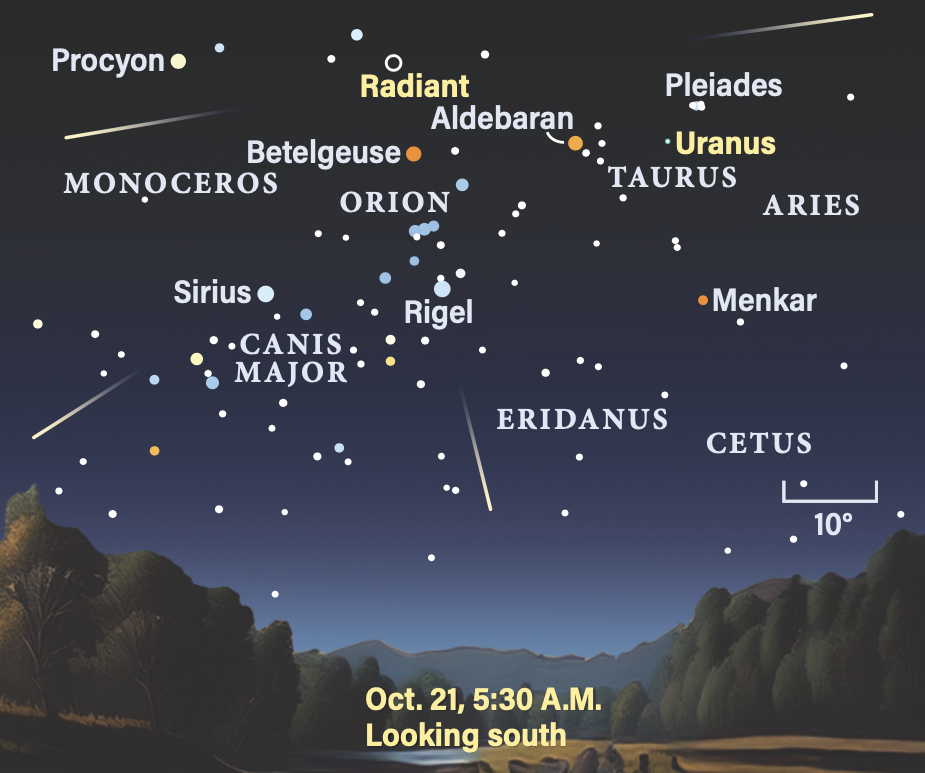

Meteor Watch: Perfect conditions

The Orionid meteor shower peaks Oct. 21, although it is active between Oct. 2 and Nov. 7. This annual event is renowned for its swift, bright meteors that radiate from the constellation Orion, near the star Betelgeuse. Under optimal conditions — clear, dark skies and minimal light pollution — viewers can expect up to 20 meteors per hour in the predawn hours when the radiant is high in the sky. The radiant rises in the east before midnight and reaches its highest point in the sky around 5:30 a.m., making the early-morning hours ideal for observation. This year the New Moon on Oct. 21 ensures dark skies, enhancing visibility. To fully appreciate the spectacle, find a dark location, lie back, and allow your eyes to adjust to the darkness.

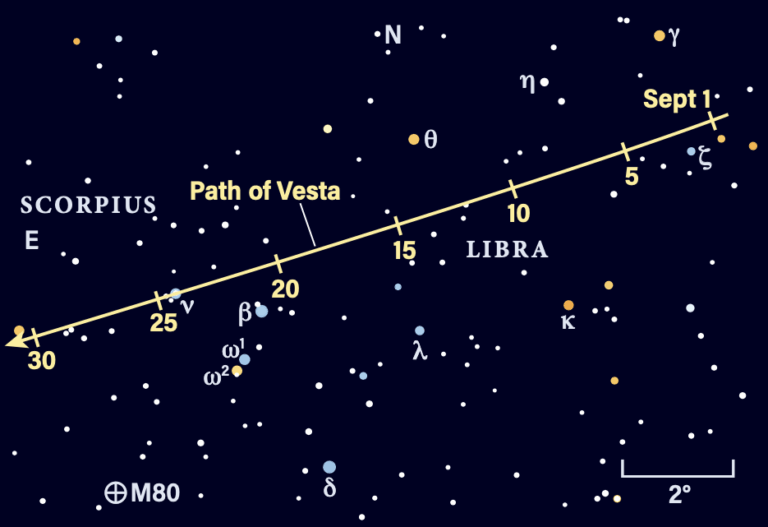

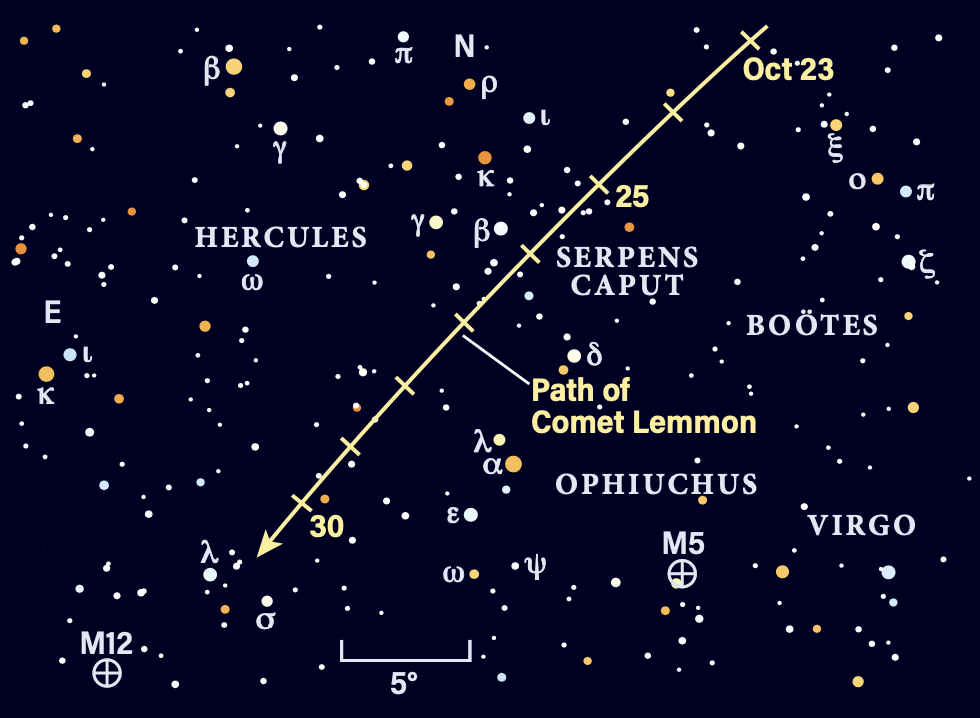

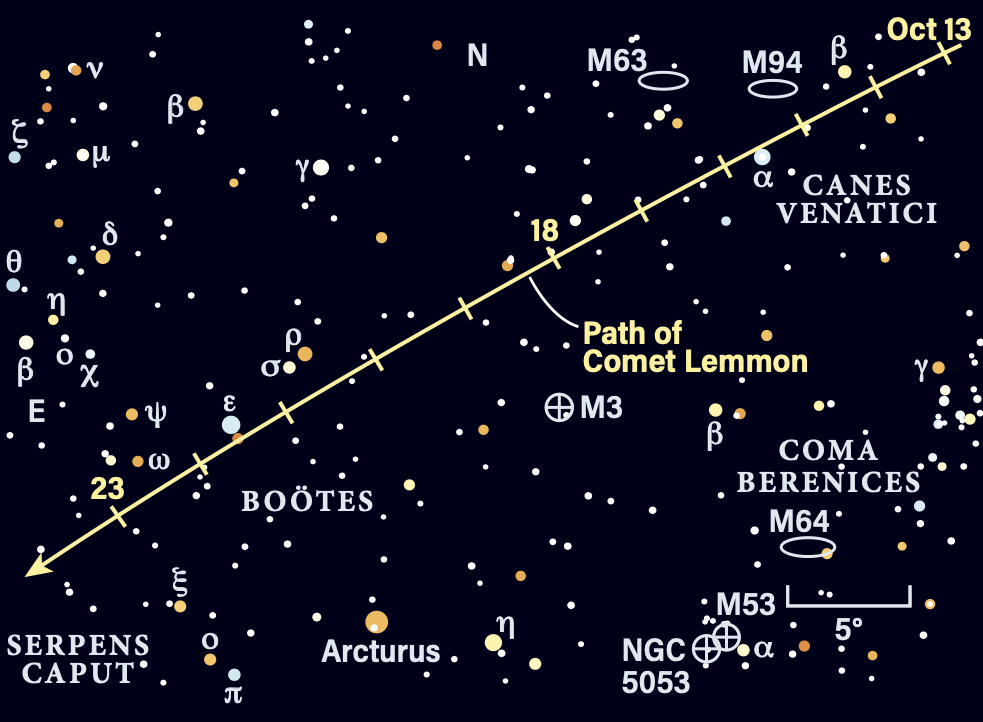

Comet Search: Watch it move!

Falling steeply into the Sun’s gravity well, Comet C/2025 A6 (Lemmon) drops in from the Oort Cloud for a brief two-month visit. By month’s end it peaks around 8th magnitude, comparable to Messier galaxies, in the northwest and is accessible to 3-inch scopes from a country location.

Discovered in January by D.C. Fuls with the Mount Lemmon Survey in Arizona, this mile-sized ball of dirt and ice is headed to a point half the Sun-Earth distance before shooting back out.

Skip October’s first two weeks, then get ready to jump. As darkness descends, Comet Lemmon is not much more than 20° high and sinks quickly into the horizon haze. Visual observers should note its position in a star field, then again 30 minutes later to see that it’s shifted 1/6 the Moon‘s apparent diameter. Imagers will be happy with the green glow from carbon emission, but the 11″ displacement for a classic one-minute “sub” will catch many off guard. Shorten your exposures below 25 seconds or so to avoid blurring details.

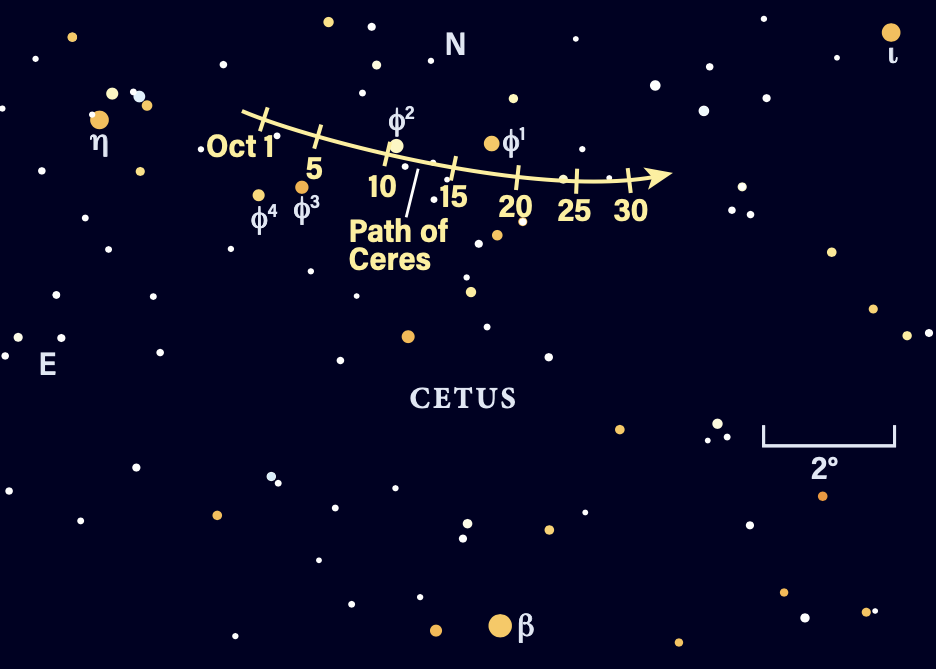

Locating Asteroids: Binoculars catch Ceres

It’s easy to follow dwarf planet 1 Ceres, sliding across the back of Cetus the Whale. In just five minutes, you can step onto the balcony or deck, swing one binocular field east of the midpoint between Saturn and the lonely but bright Beta (β) Ceti below, and note which dot is a trespasser.

Use the string of four Phi [ϕ] stars to anchor yourself. Place those in a logbook and add a few faint stars where Ceres ought to be, and by month’s end you’ll have a chain (that’s Ceres’ movement each day). At opposition on the 2nd, Ceres glows at magnitude 7.6, then fades gradually to 8.0. With a telescope you can see it move in an hour relative to background stars on the 8th, 13th, and 28th.

Did a nova just appear below Saturn? Peaking up to 2nd magnitude, the larger geostationary satellites reflect sunlight from their solar panels. Lower satellites move across the sky, but for these big birds, the sky moves slowly past them. The time of peak brightness shifts about four minutes earlier each night.

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 35° north latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

10 p.m. October 1

9 p.m. October 15

8 p.m. October 31

Planets are shown at midmonth