Key Takeaways:

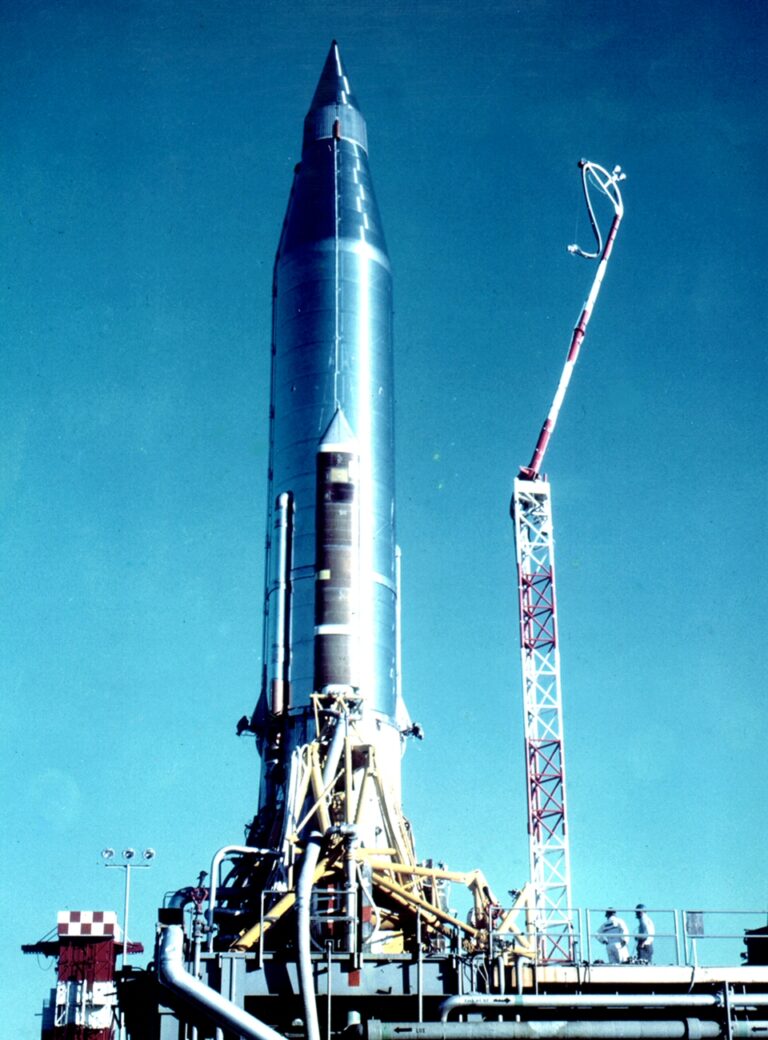

NASA marked a critical step on the journey to Mars with its Orion spacecraft during a roaring liftoff into the dawn sky over eastern Florida on Friday, December 5, 2014, aboard a Delta IV Heavy rocket.

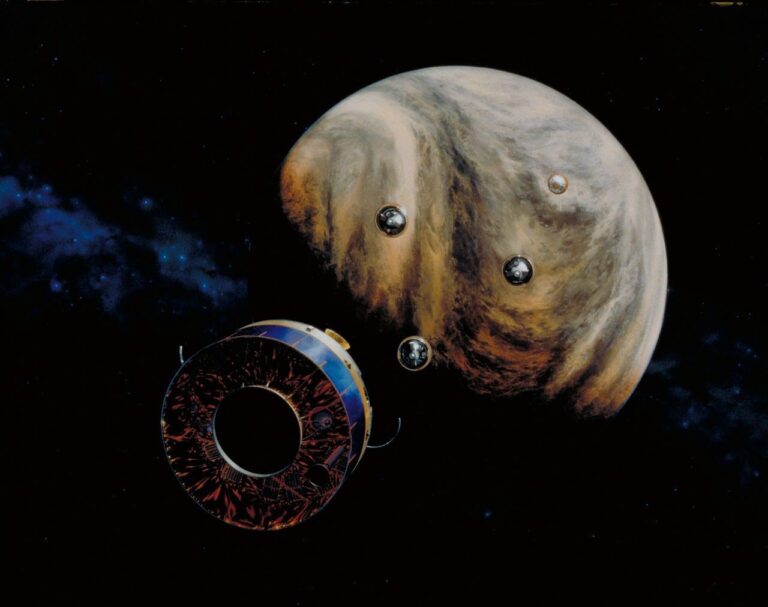

Once on its way, the Orion spacecraft accomplished a series of milestones as it jettisoned a set of fairing panels around the service module before the launch abort system tower pulled itself away from the spacecraft as planned.

The spacecraft and second stage of the Delta IV rocket settled into an initial orbit about 17 minutes after liftoff. Flight controllers put Orion into a slow roll to keep its temperature controlled while the spacecraft flew through a 97-minute coast phase.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: Continue to watch live coverage of the flight through Orion’s splashdown at about 11:30 a.m. EST at nasa.gov/nasatv.]

The cone-shaped spacecraft did not carry anyone inside its cabin but is designed to take astronauts farther into space than ever before in the future.

Orion’s first flight test is expected to be one for the books: the first mission since Apollo to carry a spacecraft built for humans to deep space, the first time NASA’s next-generation spacecraft is tested against the challenges of space, and the first operational test of a heat shield strong enough to protect against 4,000-degree temperatures.

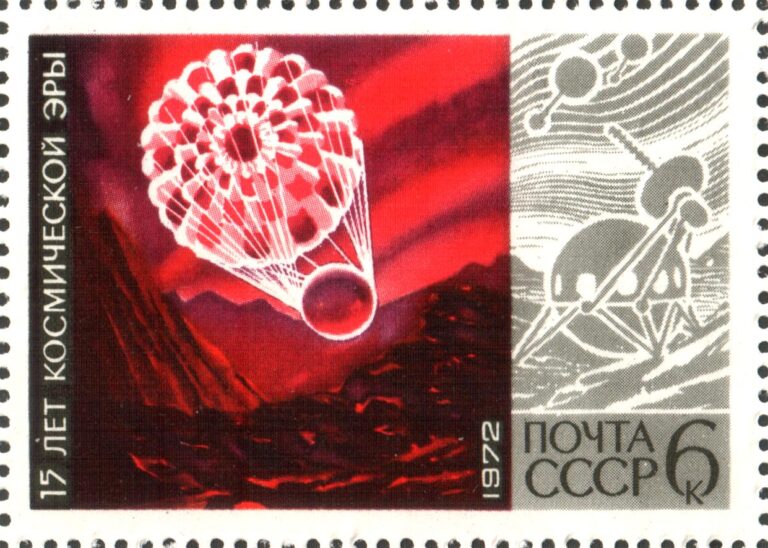

From today’s launch on a gigantic United Launch Alliance Delta IV Heavy from Florida to the expected splashdown under billowing parachutes, the mission will test many of the riskiest events Orion will see when it sends astronauts to an asteroid and onward toward Mars in the future.

“Orion is the exploration spacecraft for NASA, and paired with the Space Launch System, or SLS, rocket it will allow us to explore the solar system,” said Mark Geyer, program manager of Orion, which is based at Johnson Space Center in Houston.

While the Delta IV Heavy will send Orion on its flight test, SLS will launch the spacecraft on future missions.

NASA’s Orion program has arrived at a fulcrum point that will tell its designers and builders how it stacks up technically. It also will show that NASA is ready to take the next step on its journey into deep space – and ultimately to Mars.

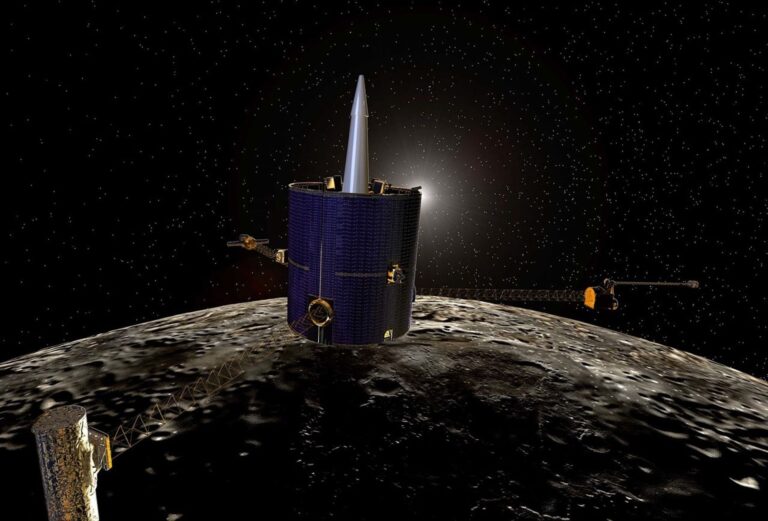

So even though Orion is poised for a mere 4.5-hour, two-orbit mission without anyone on board, the cone-shaped craft needs to perform its roster of tasks well, including an all-important descent through Earth’s atmosphere and splashdown.

“Really, we’re going to test the riskiest parts of the mission,” Geyer said. “Ascent, entry, and things like fairing separations, Launch Abort System jettison, the parachutes plus the navigation and guidance – all those things are going to be tested. Plus we’ll fly into deep space and test the radiation effects on those systems.”

The flight test began at Space Launch Complex 37 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.

The second stage will ignite again about two hours into the flight to send Orion through the Van Allen radiation belts and to a peak altitude of 3,609 miles (5,808 kilometers), some 15 times higher than the International Space Station. This is going to be a key point in the test flight as instruments inside Orion record the radiation doses inside the cabin – critical data for mission planners considering the best way to safely send astronauts into deep space in the future. Orion’s cameras will be turned off during its passes through the belts to protect them.

Three hours, 23 minutes into flight, the Orion crew module will fly on its own following separation from its service module and the Delta IV Heavy second stage. The spacecraft will be aimed at Earth’s atmosphere and it will be up to Orion’s onboard computers to set the spacecraft in the right position so its base heat shield can bear the brunt of the intense reentry heat.

Hitting the atmosphere at 20,000 mph (32,000 km/h) four hours and 13 minutes after launch, Orion will encounter about 80 percent of the heat it would endure during a return from lunar orbit with astronauts aboard. Ground controllers will lose contact with Orion for 2.5 minutes during reentry when the spacecraft is surrounded by plasma. They should regain communications with the craft just before the forward bay cover is jettisoned in a process that will begin the parachute deployment. After about four hours, 23 minutes, Orion will be bobbing in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Baja California as recovery forces move in.

Teams from NASA’s Ground Systems Development and Operations Program based at Kennedy will work with U.S. Navy and Orion prime contractor Lockheed Martin personnel to bring the spacecraft into the well deck of the USS Anchorage, an amphibious ship with a protective enclosure that will allow Orion to basically float onboard without having to be lifted by a crane. A second ship, the USNS Salvor, also will be on hand as a backup.

Many aspects of the mission point to a future as ambitious as any time in NASA’s 50-plus-year history.

With lessons learned from Orion’s flight test, NASA can improve the spacecraft’s design while building the first Space Launch System rocket, a heavy booster with enough power to send the next Orion to a distant retrograde orbit around the Moon for Exploration Mission-1. Following that, astronauts are gearing up to fly Orion on the second SLS rocket on a mission that will return astronauts to deep space for the first time in more than 40 years. These adventures will set NASA up for future human missions to an asteroid and even on the journey to Mars.

“To be able to even think about going to an asteroid and to be able to think about this kind of exploration, that’s very exciting,” Kennedy Space Center Director Bob Cabana said. “I think there’s a genuine, positive atmosphere, and I don’t think it’s confined to just Kennedy. You go across all the NASA centers and I think the team is really excited about the future.”

And while all that work is happening on the ground, astronauts on the International Space Station will continue the groundbreaking research that is already adding to humanity’s understanding of everything from long-duration spaceflight to the continued experimentation on products and processes that improve life on Earth.

None of those plans has caused NASA or Lockheed Martin, which is operating this flight test, to look past the crucial steps needed to make this mission a success.

Lockheed Martin assembled the spacecraft in the high bay at the Operations and Checkout Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, a facility recently named for Neil Armstrong, first man to walk on the moon.

While the mission is expected to make a huge impact on the way the next Orion is built, many lessons from the buildup of this spacecraft are already being incorporated in the planning for the next one, Geyer said.

“This has shown it’s a good design, it’s a good mission and now it’s time to go fly,” Geyer said.