Key Takeaways:

New data from the Satellites Around Galactic Analogs (SAGA) Survey is reshaping our picture of the Milky Way by studying galaxies like it. Our Milky Way has a slew of smaller “satellite” galaxies bound by gravity, many of which are in the process of falling into and becoming part of our larger galaxy. But the SAGA survey, which has studied eight Milky Way-like galaxy systems in the past five years, has revealed that our satellites are much calmer — as in, less luminous and making fewer stars — than those of our “siblings.” If this trend is confirmed, it may help us better understand whether the Milky Way is normal or not. The findings thus far were published today in the Astrophysical Journal.

“Our work puts the Milky Way into a broader context,” said Risa Wechsler, a SAGA member and researcher at the Kavli Institute at Stanford University, in a press release.

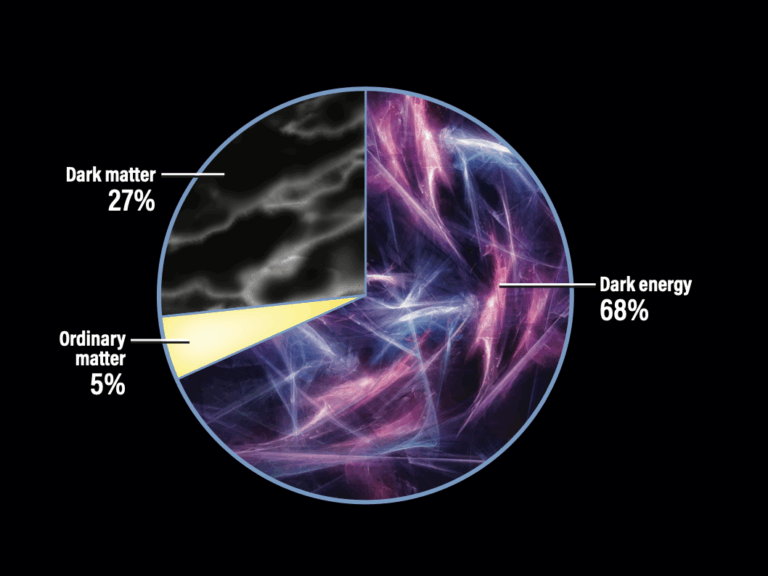

Marla Geha, first author of the paper and a researcher at Yale University, added, “Hundreds of studies come out every year about dark matter, cosmology, star formation, and galaxy formation, using the Milky Way as a guide. But it’s possible that the Milky Way is an outlier.” If so, it would affect our understanding of other galaxies, as seen through the lens of our own. Thus, it’s vital to determine “whether the Milky Way is unique, or totally normal. By studying our siblings, we learn more about ourselves,” she said.

And so far, those siblings appear to have systems of satellite galaxies actively forming new stars, and glowing brightly as a result. That’s not the case around the Milky Way, which is leading astronomers to wonder whether our galaxy is truly the “normal” benchmark we believe it to be.

In all, the SAGA survey will look at 100 Milky Way “sibling” systems. The current sample of eight, while showing a trend in satellite galaxy activity and luminosity, is still too small to draw solid conclusions. Over the next two years, the survey plans to add 25 more siblings to their dataset, which should improve astronomers’ ability to discern trends about the Milky Way and similar galaxy systems.

Armed with that knowledge, astronomers can begin to determine whether our models of galaxy behavior — largely based on our understanding of our home galaxy — are reliable, or whether they may require updating because they’re based on an abnormal example.