Key Takeaways:

The work, led by Mark Walker of Manly Astrophysics and published in the Astrophysical Journal, began with observations taken with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation’s (CSIRO) Compact Array radio telescope in Australia. While studying the quasar PKS 1322–110, it began “twinkling violently,” said Walker in a press release. When the team followed up with the 10-meter Keck telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawaii, they noticed the quasar “is very close on the sky to the hot star Spica,” said collaborator Vikram Ravi of the California Institute of Technology.

That realization brought another twinkling quasar to mind: J1819+3845, which is close to the bright star Vega on the sky. Based on that knowledge, the team examined data of J1819+3845 and a third violently twinkling quasar, PKS 1257–326, which is near the star Alhakim.

Could these alignments be pure chance? The researchers calculated that the likelihood of two twinkling quasars residing near hot stars on the sky was about one in ten million.

Based on their re-examination of data taken J1819+3845 and PKS 1257–326, “We have very detailed observations of these two sources,” said co-author Hayley Bignall of CSIRO. “They show that the twinkling is caused by long, thin structures.”

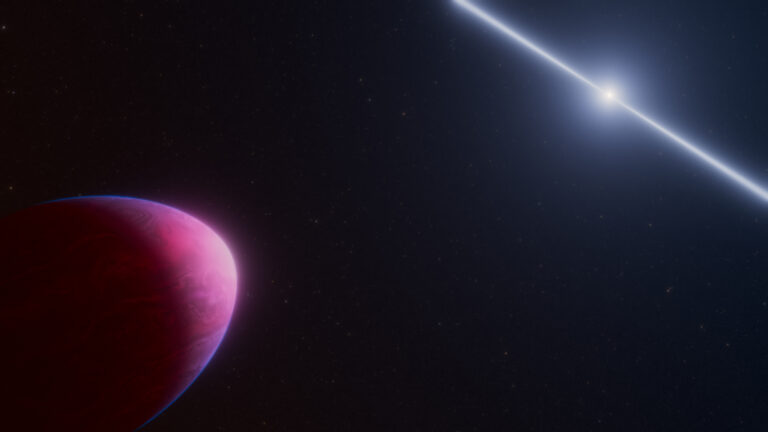

These structures, the team thinks, are filaments of warm gas around hot stars, much like the filaments seen in the Helix Nebula. The Helix Nebula contains globules of hydrogen gas, which are stretched out into filaments by ultraviolet radiation from the central star. Although the Helix Nebula is home to an older star and the globules likely formed recently, the astronomers think similar structures might sit around younger stars.

“They might date from when the stars formed, or even earlier,” said Walker. “Globules don’t emit much light, so they could be common yet have escaped notice so far.”

If so, these globules and the filaments associated with them could be responsible for the twinkling of background quasars when they affect the focus of the radio signals traveling through them, rather than changes in emission from the quasars themselves. Determining the true reason for the twinkling will tell astronomers more about both the physics of distant quasars and the stars in our own galaxy.