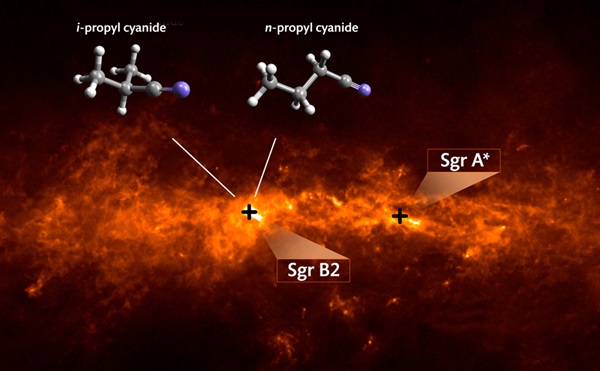

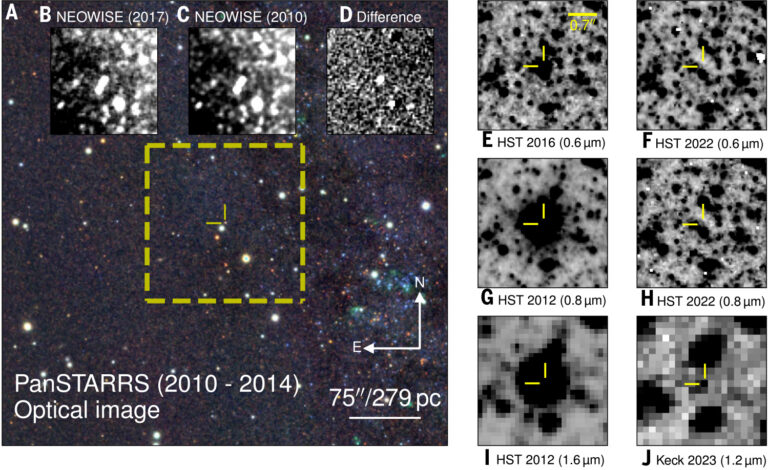

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), researchers studied the gaseous star-forming region Sagittarius B2.

Organic molecules usually found in these star-forming regions consist of a single “backbone” of carbon atoms arranged in a straight chain. But the carbon structure of isopropyl cyanide branches off, making it the first interstellar detection of such a molecule, said Rob Garrod from Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

This detection opens a new frontier in the complexity of molecules that can be formed in interstellar space and that might ultimately find their way to the surfaces of planets, said Garrod. The branched carbon structure of isopropyl cyanide is a common feature in molecules that are needed for life — such as amino acids, which are the building blocks of proteins. This new discovery lends weight to the idea that biologically crucial molecules, like amino acids that are commonly found in meteorites, are produced early in the process of star formation — even before planets such as Earth are formed.

Garrod, along with Arnaud Belloche and Karl Menten, both of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, and Holger Müller of the University of Cologne, sought to examine the chemical makeup of Sagittarius B2, a region close to the Milky Way’s galactic center and an area rich in complex interstellar organic molecules.

With ALMA, the group conducted a full spectral survey looking for fingerprints of new interstellar molecules — with sensitivity and resolution 10 times greater than previous surveys.

The purpose of the ALMA Observatory is to search for cosmic origins through an array of 66 sensitive radio antennas from the high elevation and dry air of northern Chile’s Atacama Desert. The array of radio telescopes works together to form a gigantic “eye” peering into the cosmos.

“Understanding the production of organic material at the early stages of star formation is critical to piecing together the gradual progression from simple molecules to potentially life-bearing chemistry,” said Belloche.

About 50 individual features for isopropyl cyanide and 120 for normal-propyl cyanide — its straight-chain sister molecule — were identified in the ALMA spectrum of the Sagittarius B2 region. The two molecules — isopropyl cyanide and normal-propyl cyanide — are also the largest molecules yet detected in any star-forming region.