Three massive volcanic eruptions occurred on Jupiter’s moon Io, a satellite the size of Earth’s moon, within a two-week period last August. Astronomers think that these presumed rare outbursts, which can send material hundreds of miles above the surface, might be much more common than previously thought.

“We typically expect one huge outburst every one or two years, and they’re usually not this bright,” said Imke de Pater, professor and chair of astronomy at the University of California (UC), Berkeley, and lead author of one of two papers describing the eruptions. “Here we had three extremely bright outbursts, which suggest that if we looked more frequently we might see many more of them on Io.”

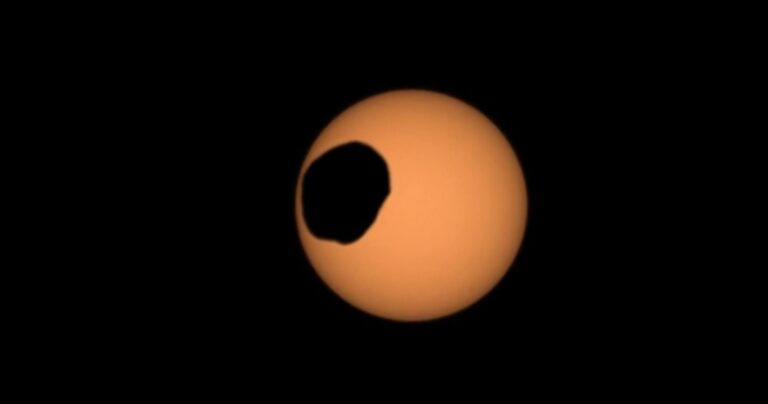

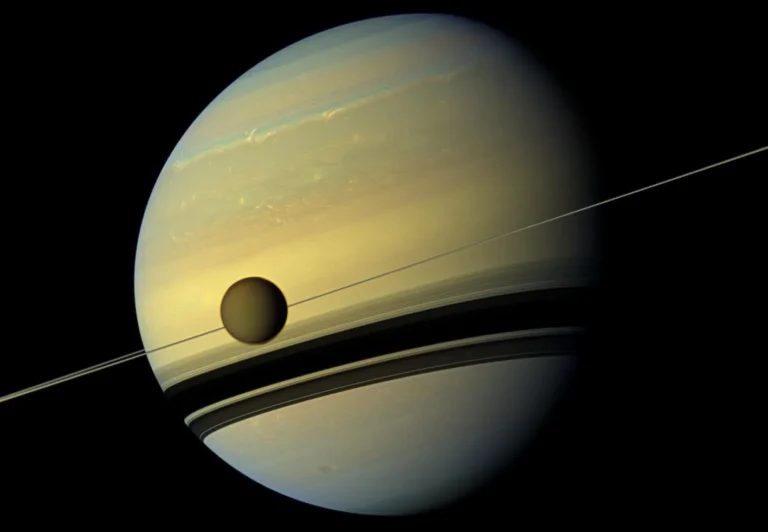

Io (pronounced ee-o or eye-o), the innermost of Jupiter’s four large “Galilean” moons, is about 2,300 miles (3,700 kilometers) across and the most volcanically active moon or planet in our solar system. It also is the only body in the solar system with volcanoes erupting extremely hot lava other than Earth. Because of Io’s low gravity, large volcanic eruptions produce an umbrella of debris that rises high into space.

De Pater’s long-time colleague and coauthor Ashley Davies, a volcanologist with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, California, said that the recent eruptions match past events that spewed tens of cubic miles of lava over hundreds of square miles in a short period of time.

“These new events are in a relatively rare class of eruptions on Io because of their size and astonishingly high thermal emission,” he said. “The amount of energy being emitted by these eruptions implies lava fountains gushing out of fissures at a very large volume per second, forming lava flows that quickly spread over the surface of Io.”

All three events, including the largest, most powerful eruption of the trio on August 29, 2013, were likely characterized by “curtains of fire,” as lava blasted out of fissures perhaps several miles long.

The papers — one with lead author Katherine de Kleer, a UC Berkeley graduate student, and the other with lead author de Pater — have been accepted for publication in the journal Icarus.

Lava fountains on Io

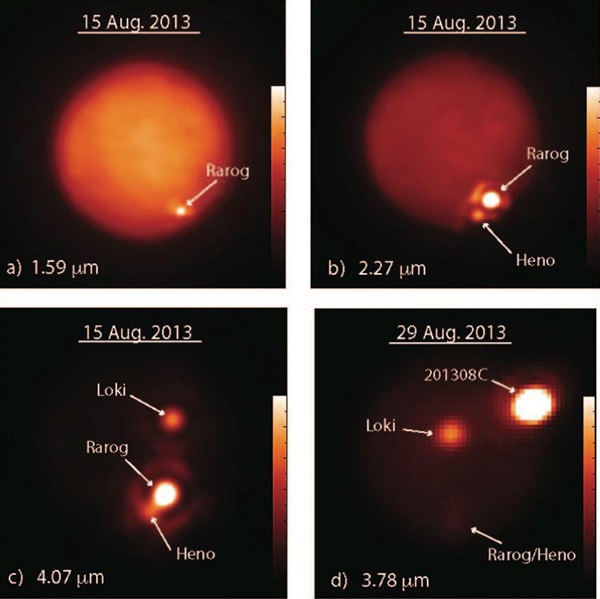

De Pater discovered the first two massive eruptions on August 15, 2013, using one of two 10-meter telescopes operated by the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii. Her team specifically used the near-infrared camera (NIRC2) coupled to the adaptive optics system on the Keck II telescope. The brightest eruption, at a caldera named Rarog Patera, was calculated to have produced a 50 square-mile (130 square km), 30-foot thick (9 meters) lava flow, while the other, near a caldera called Heno Patera, produced flows covering 120 square miles (320 square km). Both are in Io’s southern hemisphere, near its limb, and were nearly gone when imaged five days later.

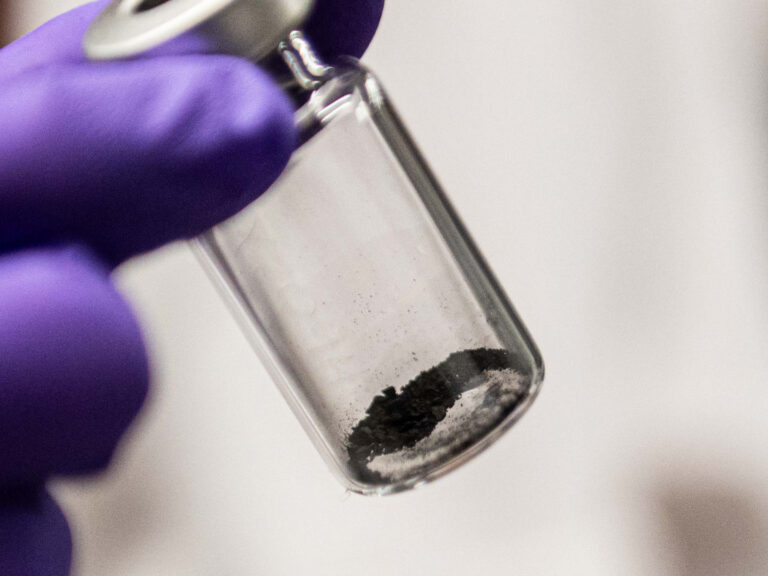

A third and even brighter eruption — one of the brightest ever seen on Io — showed up on August 29 at the start of a year-long series of Io observations led by de Kleer, using both the Near-Infrared Imager with adaptive optics on the Gemini North telescope on Mauna Kea, and the SpeX near-infrared spectrometer on NASA’s nearby Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF). De Kleer used the fortuitous detection of this outburst simultaneously at Gemini and the IRTF to show that the eruption temperature is likely much higher than typical eruption temperatures on Earth today, “indicative of a composition of the magma that on Earth only occurred in our planet’s formative years,” she added.

At the time of the observation, the thermal source had an area of up to 32 square miles (83 square km). The modeled temperature of the lava indicated it barely had time to cool, suggesting that lava fountains dominated the event.

“We are looking at several cubic miles of lava in rapidly emplaced flows,” said Davies, who has developed models to predict the volume of magma erupted based on spectroscopic observations. “This will help us understand the processes that helped shape the surfaces of all the terrestrial planets, including Earth, and the Moon.”

The team tracked the heat of the third outburst for almost two weeks after its discovery to investigate how volcanoes influence Io’s atmosphere and how these eruptions feed a “doughnut” of ionized gas — the Io plasma torus — that surrounds Jupiter near Io’s orbit. De Kleer timed her Gemini and IRTF observations to coincide with observations of the plasma torus by the Japanese Hisaki spacecraft orbiting Earth so she can correlate the different data sets.

A volcanic laboratory

Scientists first saw volcanoes on Io in 1979, and subsequent studies by the Galileo spacecraft, which first flew by Io in 1996, and ground-based telescopes show that eruptions and lava fountains occur constantly, creating rivers and lakes of lava. But large eruptions, those that create vast lava flows in some cases thousands of square miles in area, were thought to be rare. Only 13 were observed between 1978 and 2006, in part because only a handful of astronomers, de Pater among them, regularly scan the jovian moon.

Davies’ interest in Io’s volcanoes arises from the moon’s resemblance to an early Earth when heat from the decay of radioactive elements — much more intense than radiogenic heating today — created exotic, high-temperature lavas. Io remains volcanically active for a different reason — Jupiter and the moons Europa and Ganymede constantly tug on it — but the current eruptions on Io are likely similar to those that shaped the surfaces of inner solar system planets such as Earth and Venus in their youth.

“We are using Io as a volcanic laboratory, where we can look back into the past of the terrestrial planets to get a better understanding of how these large eruptions took place, and how fast and how long they lasted,” Davies said.

In a third paper to be published in Icarus, de Pater, Davies, and their colleagues summarize a decade of Io observations from the Keck II and Gemini telescopes. Their map of Io’s surface pinpoints more than two dozen hot spots whose spatial distribution changed significantly between 2001 and 2010. In 2010, two volcanic centers dominate the hot spots: Loki Patera, an extremely large active lava lake on Io, and Kanehekili Fluctus, an area of continuing pahoehoe lava flows.

The team hopes that monitoring Io’s surface annually will reveal the style of volcanic eruptions on the moon, constrain the composition of the magma, and accurately map the spatial distribution of the heat flow and potential variations over time. This information is essential to improving scientists’ understanding of the physical processes involved in the heating and cooling processes on Io, de Pater said.