No human has yet gone astray between worlds. But Buzz Aldrin came close during the final Gemini mission, when the navigation computer went on the fritz. Figuring out how to manually get all the way to the invisible, high-orbit target Agena rocket through calculations alone solidified his “Dr. Rendezvous” nickname and may have earned him that coveted spot on Apollo 11.

Some inanimate object was lost, too, back in 1969 during the Apollo 12 mission. For days, the crew watched a large, distant tumbling object out their window that kept pace with them on their way to the Moon. “We’ll assume it’s friendly,” quipped Dick Gordon. Nothing was supposed to be there. To this day, no one is sure what it was.

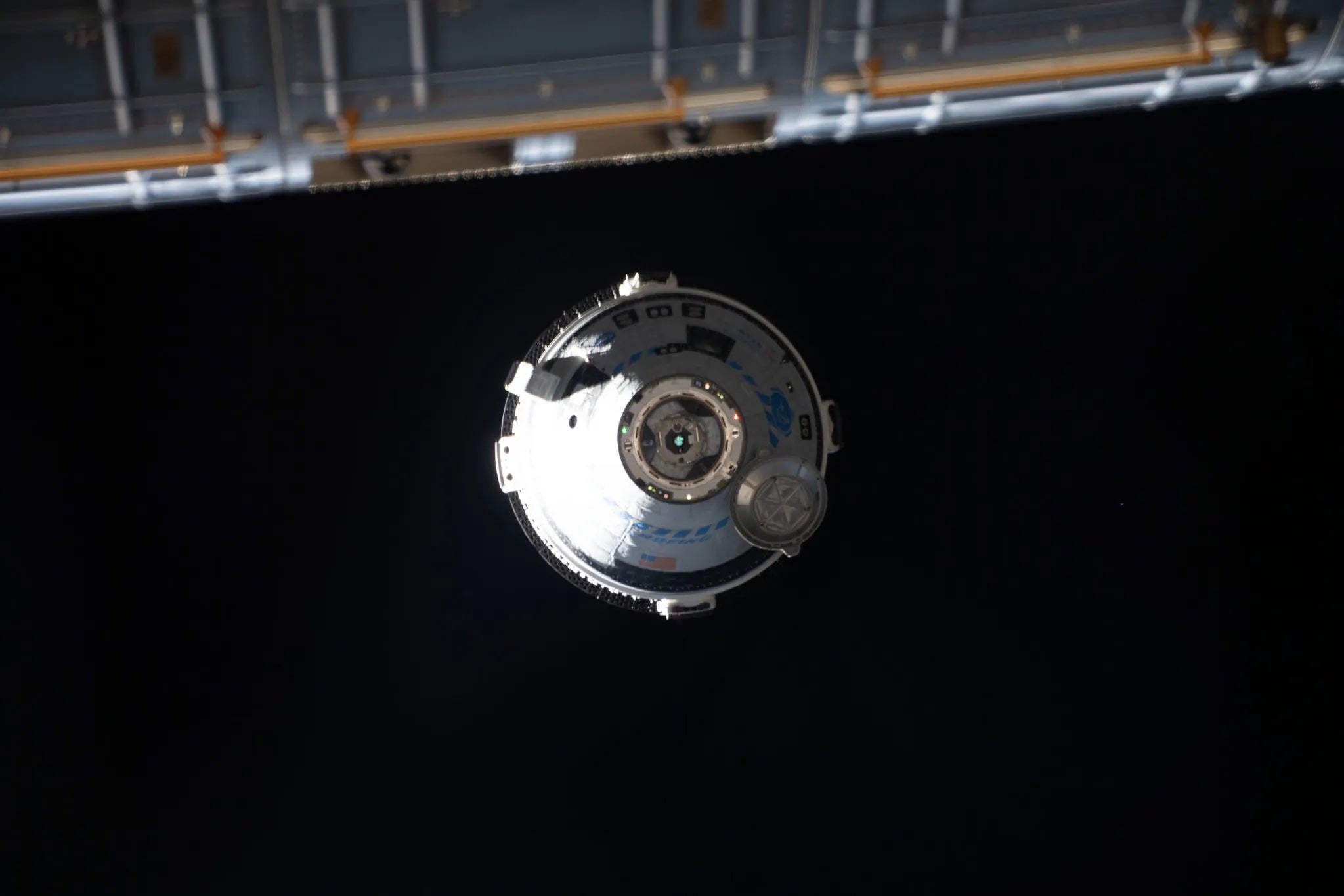

A couple of robots have gotten lost much farther away — at Mars. On August 21, 1993, when the Mars Observer spacecraft reached the Red Planet’s vicinity, all contact was suddenly lost. What happened? No one ever decisively figured it out. The craft might have obeyed its onboard computer instructions, and maybe it’s still orbiting Mars today. More likely a fuel line blew, with the spray making the craft spin crazily. It may have crashed, or perhaps it’s orbiting the Sun.

For us as observers, getting lost more commonly means gazing into a gorgeous rural firmament and having no idea what we’re seeing. These nights, not too many backyard astronomers know all that stuff beneath Orion that constitutes Lepus the Hare and Eridanus the River to its right. Even worse are the faint enigmatic overhead patterns of Lynx the Lynx and Camelopardalis the Giraffe.

GETTING LOST AMONG THE STARS IS ACTUALLY A WONDERFUL THING. IT CONJURES A SENSE OF INFINITUDE.

Getting lost among the stars is actually a wonderful thing. It conjures a sense of infinitude. And, hey, don’t we all need periodic vacations from our logical minds? The stars are epic and soothing when you don’t know their Greek letter labels. Anyway, you’ll hear no romantic sighs when you point out constellations like “the fly” and “the stern,” Musca and Puppis.

Ironically, professional astrophysicists are the ones who get lost most easily in the real night sky. Many do not know the constellations, with some notable exceptions. But astronauts do. A few, like winsome Andy Thomas, who grew up in the Outback and spent nearly half a year cumulatively in space, know the sky really well. Fanatics who truly know the heavens have a lot of fun. They never need charts to locate Messier objects.

But go to Chile or New Zealand, and it’s a new ball game. Everything’s upside down. Huge vacant swatches around Tucana the Toucan and Fornax the Furnace become terra incognito. After some basic star-hopping from Crux the Cross or the Magellanic Clouds, I go, “OK, there’s Canopus and the False Cross and, wow, OK, Fomalhaut — high up instead of low like back home,” and I’m soon reoriented enough to lead a group who knows even less. A decade ago, I had to memorize that southernmost quarter of the firmament from scratch, with a brain containing 10 percent fewer neurons than before college.

Learning the sky is a venerable pastime. There’s not much ego: Everyone knows that the cosmos is basically made of magical mystery material. Anyway, only some five dozen stars still have names in common use, so it’s actually not hard to identify them all. Yes, every star. Maybe 200 if you include the fainter Bayer designations. Tackle one constellation per night. Got the time? Out of good books to read? (Don’t forget my latest, Zoom.) Are you in or out?

And when we meet someday, share what you know, and we’ll enjoy the ancient scene together, laughing about some of the odd stories and curious pronunciations. And if some faint patch makes us both wonder, “Is that still Aquarius, or is it part of Pisces?” we can smile and shrug. Just as people have done for millennia when they’ve been lost in space.

Contact me about my strange universe by visiting http://skymanbob.com.