Key Takeaways:

It took a few attempts, but JWST has finally found strong evidence of an atmosphere around a rocky world outside our solar system. To add to the intrigue, this isn’t the planet’s original atmosphere — it’s a second atmosphere produced by volcanic activity. This history offers clues to how planets in otherwise inhospitable environments might be able to cling to habitable conditions.

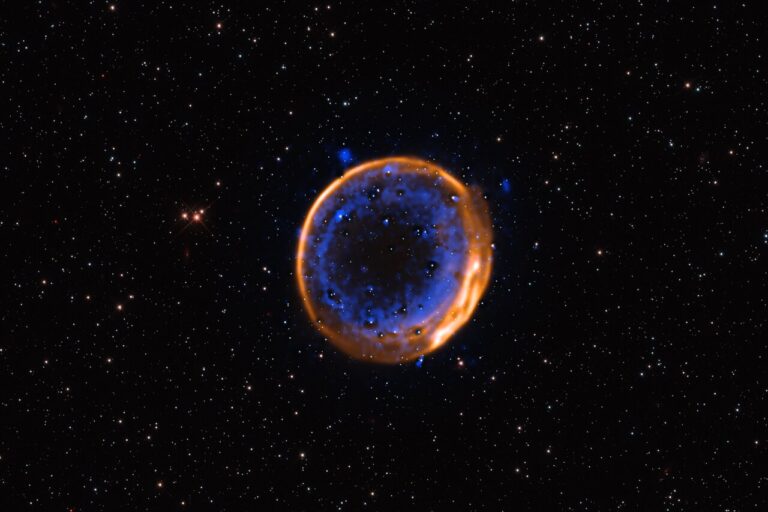

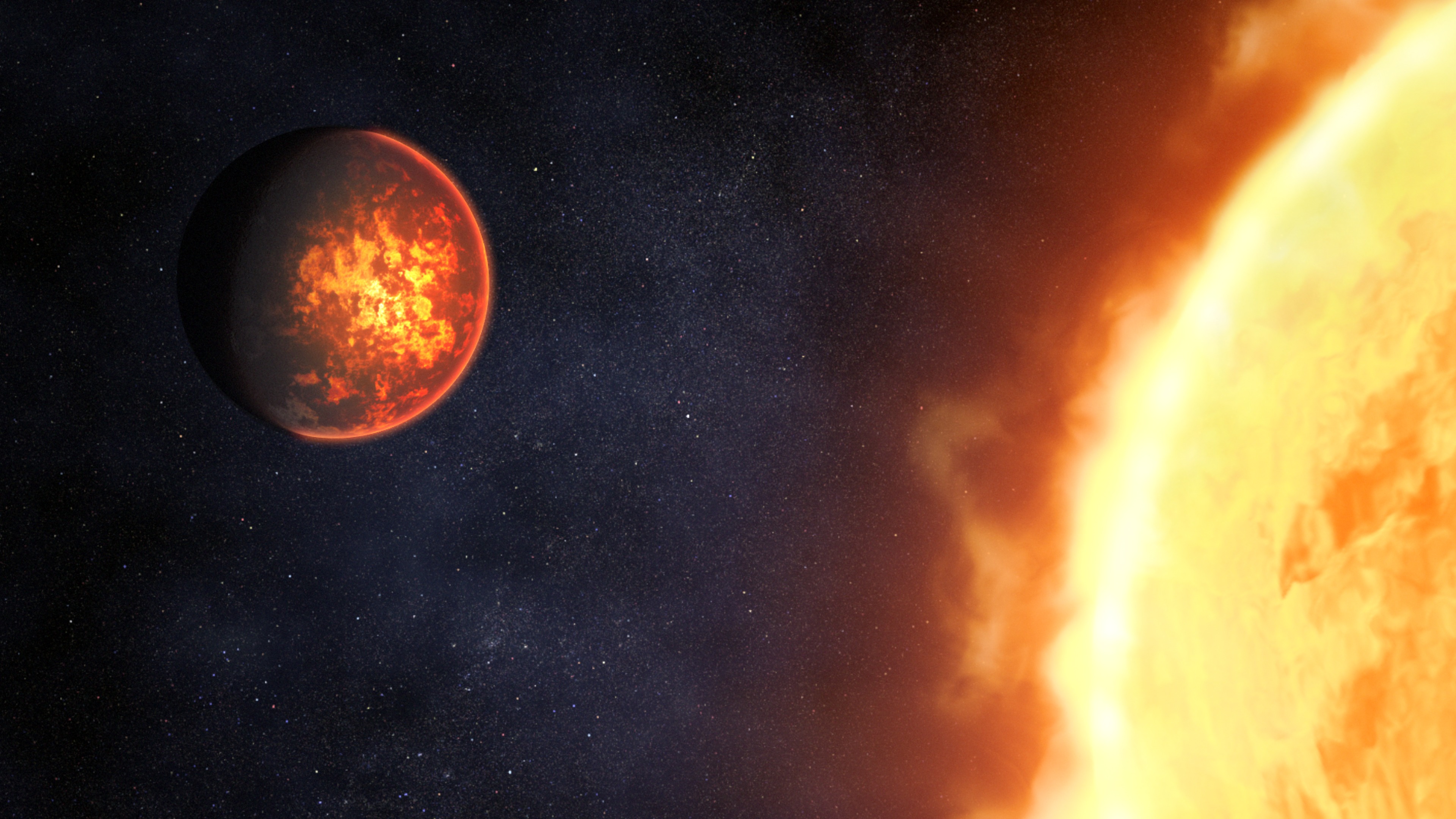

The new observations, published May 8 in Nature, focus on the planet 55 Cancri e. It’s about twice the size of Earth and eight to nine times its mass. The planet is also likely covered in oceans of magma. It completes an orbit around its home star in about 17 hours — one of the fastest known orbital periods of any exoplanet. This leads to extreme conditions around its surface, with temperatures likely exceeding 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit — hot enough to melt most metals — and an intense bombardment of radiation from its host star.

As a result, the original atmosphere should be long gone. But by using JWST to measure the infrared light emitted by the planet, a team led by researchers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) in Pasadena, California, discovered the likely presence of carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide gas around the planet — marking the first time JWST has found strong signs of an atmosphere around a rocky planet.

The team also found no evidence for helium and hydrogen — the most common elements in the universe, which would have been part of the planet’s initial atmosphere when it formed. This means that the atmosphere detected is likely the planet’s secondary atmosphere. It seems that, despite the violent winds from its nearby star, continuous volcanic activity and the gravity of the planet have allowed the planet to remain enshrouded in a relatively thick atmosphere.

In short, 55 Cancri e shows that just because a planet loses its atmosphere, that doesn’t mean that it can’t gain a new one.

Emission by subtraction

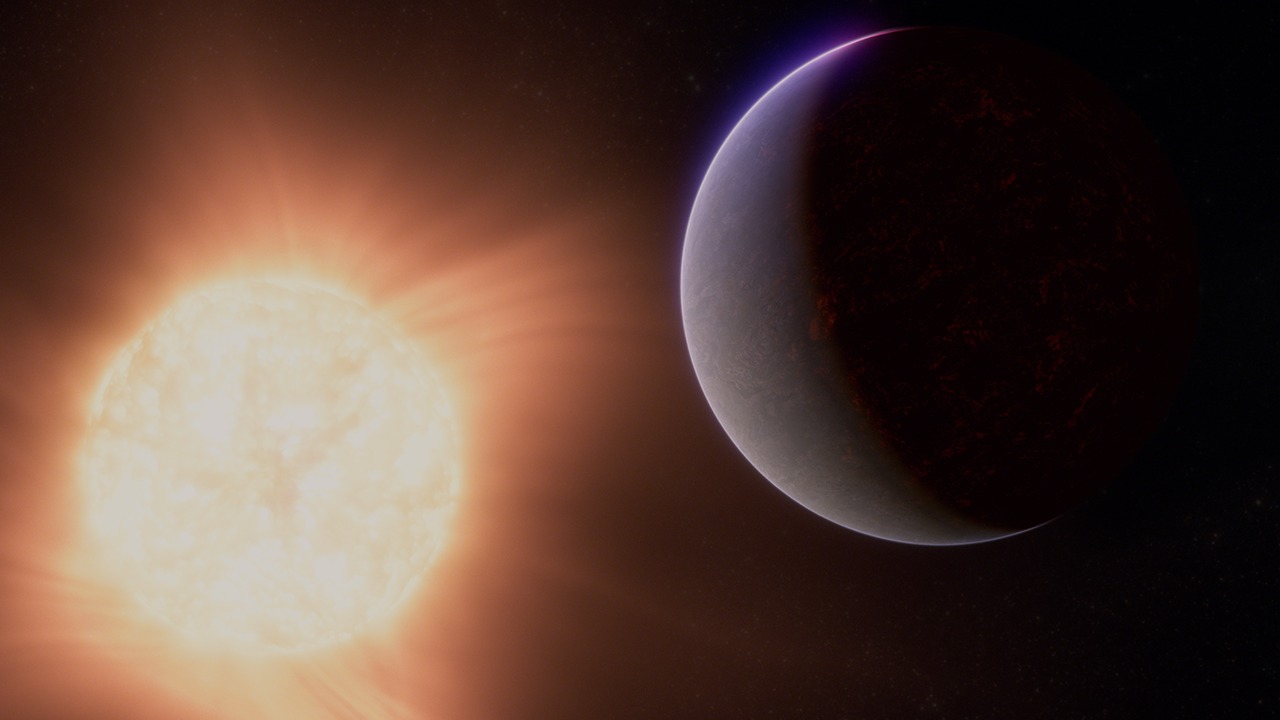

The study made use of a technique called secondary eclipse spectroscopy, which is possible when a planet’s orbit takes it behind its host star from our point of view. When the planet is eclipsed, astronomers can isolate the light coming from the host star and subtract it from observations of the full system, leaving behind the infrared light coming from the planet.

Though JWST’s suite of instruments includes a set of spectrometers, the atmospheric gasses weren’t detected by them directly. Instead, the astronomers behind the study looked at other properties of the atmosphere via the secondary eclipse, including its reflectivity. Then they ran simulations on a variety of possible atmospheric types that would give off similar signals.

The team found that the best match was a mix of carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen gas. This would also track with a planetary atmosphere driven in part by volcanism.

A second chance at life?

To date, observations of Earth-like planets in the habitable zone of their stars have not yielded definitive detections of an atmosphere — their atmospheres have been mostly or completely stripped away by intense flares and the violent winds produced by their stars.

For instance, astronomers have come up empty using JWST to search for atmospheres around planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system. This system features seven Earth-sized planets, at least three of them in their host star’s habitable zone, where the surface temperature should allow water to be in liquid form.

While 55 Cancri e itself is not habitable, the possibility of secondary atmospheres developing on worlds that are could alter our understanding of how likely a planet is to support life.

“I’m quite confident that JWST will provide a lot of information about the ability of rocky planets of various sizes and temperatures to develop a secondary atmosphere,” says Renyu Hu, a planetary scientist at JPL and lead author of the paper. “We can use that to calibrate our models, and eventually, we will have a better understanding of the emergence of habitable worlds.”