Key Takeaways:

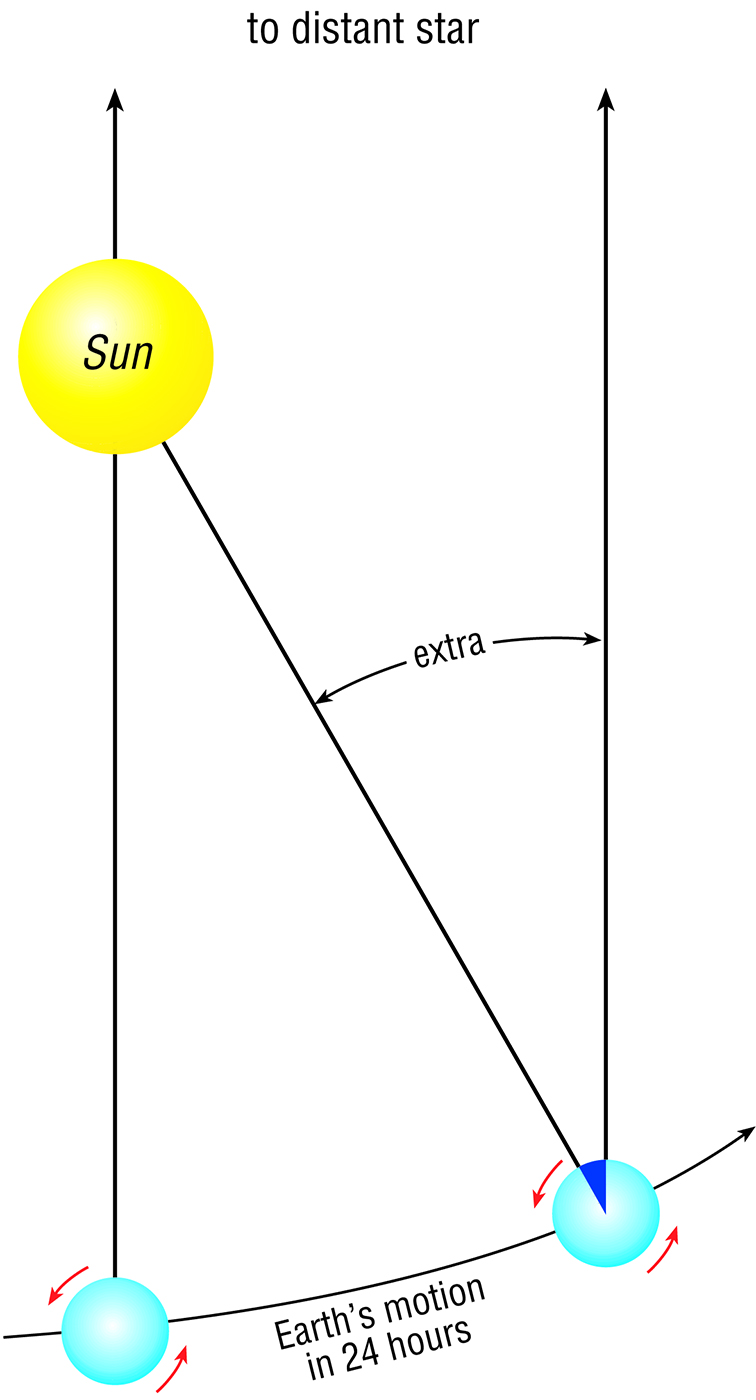

Let’s kick things off in Capricornus. In the northwestern corner of this triangular constellation await the pretty double stars Alpha (α) and Beta (β) Capricorni, which fit into the same binocular field. Even the tiniest pocket binoculars can resolve the two 4th-magnitude stars that compose Alpha Capricorni, properly named Algedi. They are not a true physical pairing, however. Instead, the stars only appear aligned as seen from Earth. The western sun, Alpha1, is 690 light-years from us while Alpha2 is just 109 light-years away.

The two suns of Dabih (Beta Capricorni), on the other hand, form a true binary system. The brighter, dubbed Dabih Major, shines with an orange color at magnitude 3.1 while its companion, Dabih Minor, is only magnitude 6.1 and looks slightly bluish. Both are 330 light-years away, and about 1/3 light-year separates them.

Our next target stood out to German-born English astronomer William Herschel. He nicknamed Mu (μ) Cephei the “Garnet Star” because of its striking orange-red color. Mu is one of the largest and brightest red supergiants in the Milky Way, with a diameter spanning farther out than Saturn’s orbit. View the Garnet Star and pure-white Alderamin (Alpha Cephei) in the same field to enhance the ruby color. Like most red supergiants, Mu also pulsates: Over a semiregular period of about 850 days, it cycles between magnitude 3.4 and 5.1.

Heading back to observing star clusters, extend a line from Schedar (Alpha Cassiopeiae) to Caph (Beta Cassiopeiae), the westernmost stars in Cassiopeia’s W asterism, and continue an equal distance farther northwest to spot M52, one of my favorite autumn open clusters. There, you should spot a slender four-star diamond-shaped asterism, with M52 just to its south. Two hundred stars call this cluster home, but only a few are bright enough to crack the binocular barrier. The rest blend into a cloud of misty starlight.

Next, scan about one-third of the way from Segin toward Polaris (Alpha Ursae Minoris). Pause when you spot the Keystone asterism formed by 40, 42, 48, and 50 Cassiopeiae, and then look carefully inside. Can you see a dim smudge? If so, you’ve spotted Collinder 463, a little-known collection of about eighty 8th-magnitude and fainter suns. Take a careful look. Does the cluster appear crescent-shaped to you, as some report?

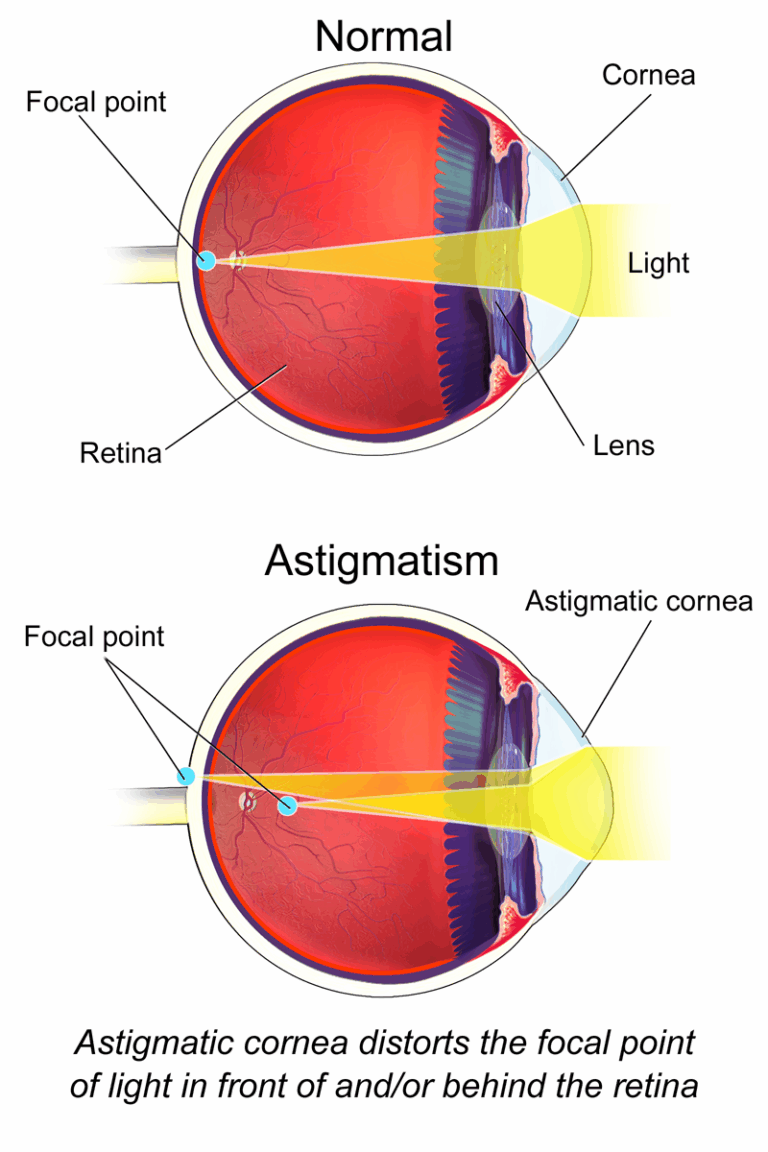

For another variable star, head to Algol (Beta Persei), the famous “Demon Star” in Perseus that is fun to follow through binoculars. Every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes, Algol “blinks” at us as it drops from magnitude 2.1 to 3.4. These changes result from a much dimmer companion star passing in front of the binary system’s primary sun. Each eclipse lasts about 10 hours. Time it for yourself to see the universe in action.

Our final target sits in Camelopardalis. While scanning the seemingly barren constellation with his 7×35 binoculars more than three decades ago, the late Canadian amateur astronomer Lucian Kemble stumbled upon, as he described it, “a beautiful cascade of faint stars tumbling from the northwest down to the open cluster NGC 1502.” Kemble’s Cascade, as this asterism is now known, spans 2.5°. A lone magnitude 5 sun at midspan highlights this curious chain of some sixteen stars between 7th and 9th magnitude. This stellar stream flows some 15° east of Segin. And once you spot Kemble’s Cascade, be sure to look for NGC 1502 at its southern tip.

These are just some of the targets in autumn’s binocular universe. If it’s clear tonight, head outside to enjoy a bit of what the season has to offer. And as always, when it comes to stargazing, remember that two eyes are better than one.