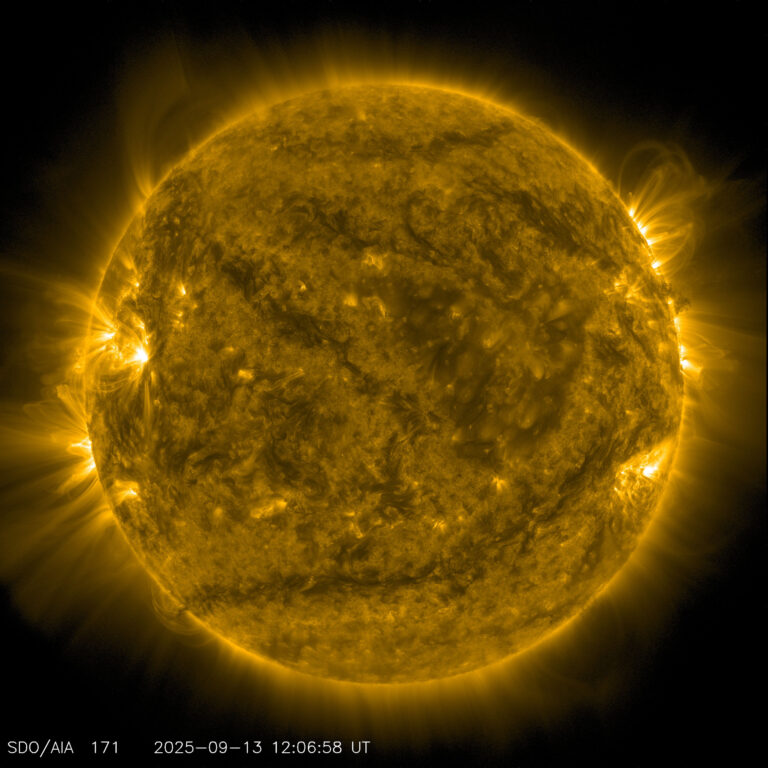

All living creatures are affected by the cycles of celestial objects. Humans have always been locked into the rhythms of sunrise and sunset, the phases of the Moon, and the seasons. We left some of this behind by lighting the night and becoming urbanized. But astronomical clocks captured those rhythms by displaying the movements of the heavens, regulating our lives by tracking and dividing the day, months, and years. For centuries, these analog devices served us well.

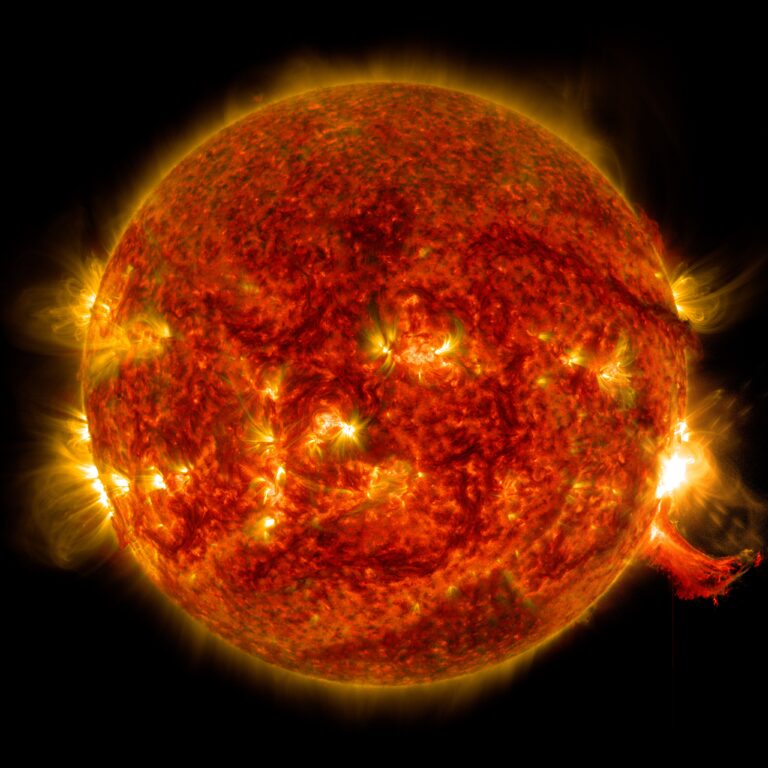

With no gears or moving hands, but rather a gnomon that projects a shadow on a dial plane to measure the passage of time at a specific location, sundials are the essence of an astronomical timekeeper. The Sun reaching the midpoint of its daily trip across the sky was the first important division of the day. Later, the day was divided into hours. These simple timekeepers remained important until the mid-19th century, long after the mechanical clock rose to dominance; today, these astronomical “clocks” have become garden ornaments.

A thousand years ago, the brilliant Chinese engineer Su Song designed and built one of the earliest astronomical clocks on record. The 40-foot (12 meters) tower was filled with gears that were turned by hydraulic power. On the top platform, a massive bronze celestial globe was located. (Unfortunately, the clock was dismantled in 1127, so you can’t visit it.)

In Europe during the Middle Ages, it was the duty of some unfortunate monk or nun to rise at designated times and ring a bell to call the brothers or sisters to prayer. They were a kind of manual clock. In fact, the word clock may derive from the Medieval Latin word clocca, meaning “bell.” These church bells divided the day into canonical hours – not 1:00, 2:00, 3:00, as we now mark the time, but eight liturgical hours such as Matins, Compline, Lauds, and Vespers. Because the hours were tied to the rising and the setting Sun, they were not uniform throughout the year. And at times, even the most devout monk might oversleep. By the late 11th and early 12th centuries, mechanical systems had taken over the ringing of church bells.

Churches soon added dials and hands to their turrets to indicate the hour for those who passed by. By the late 14th and early 15th centuries, many major European cities commissioned their own magnificent clocks. Along with the time of day, these clocks also displayed a great deal of astronomical information. I’ve selected three of the greatest of these — plus one modern masterpiece — in the hopes that, if you’re anywhere in Europe, you might visit them.

Head to Prague

When Tycho Brahe and his reluctant assistant, Johannes Kepler, arrived in Prague in 1599, they must have marveled at the city’s astronomical clock. Built in 1410, the Prague Orloj is located on the wall of the old city hall and is one of the oldest working clocks in the world. Near the end of World War II, the clock was nearly destroyed by Nazi attacks, but three years later, local citizens united to repair it. Over its six centuries of operation, the Orloj has undergone several other bouts of refurbishment and restoration, most recently in 2018. When you visit the city, you can find the clock by walking down a narrow street and turning into a small courtyard.

For those with the patience to study the dial more closely, there is a great deal of astronomical information (all set for the latitude of Prague): Sunrise and sunset are displayed on the dial, along with seasonal variations in daylight and darkness. The zodiacal locations of the Sun and the Moon are shown, along with the Moon’s phase.

The Prague Orloj was more than a tour de force of civic pride. Well into the 18th century, astrology played a major role in daily life. Clocks such the Orloj provided vital astronomical information for making astrological predictions. Tycho’s new patron in Prague, Rudolf II, was obsessed with astrology, and Tycho and Kepler spent much of their time providing charts and horoscopes to the emperor. If you visit this historic clock, decide for yourself if they consulted it in their astrological efforts.

Just outside London

England’s King Henry VIII was a towering figure surrounded by drama and intrigue. One of Henry’s favorite residences was Hampton Court Palace. Originally built in 1514 by Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, Archbishop of York, the palace has a massive and unique astronomical clock mounted in the tower of what is now called Anne Boleyn’s Gate. With a dial more than 10 feet (3 m) in diameter, it was used for astronomical and astrological purposes and for navigation.

Like the Prague Orloj, the Hampton Court clock shows the time of day on a ring marked in 24-hour increments. This clock has three rotating dials, which provide the location of the Sun along the zodiac, the phase and age of the Moon, and various calendar functions. The outer dial takes a year to rotate once and shows months and days. The second dial shows the age and phase of the Moon.

Because Hampton Court Palace is located about 12 miles (19 kilometers) from the center of London, Henry’s royal court used the River Thames to travel there. This could be dangerous because of the river’s tidal flow. However, the clock’s central dial provides times when the Moon crosses the meridian. With this information, the boatman knew when it was safe to travel on the river.

You don’t need to navigate the Thames, though. You can either drive to the Palace or take the train. From the train station, it’s only a five-minute walk.

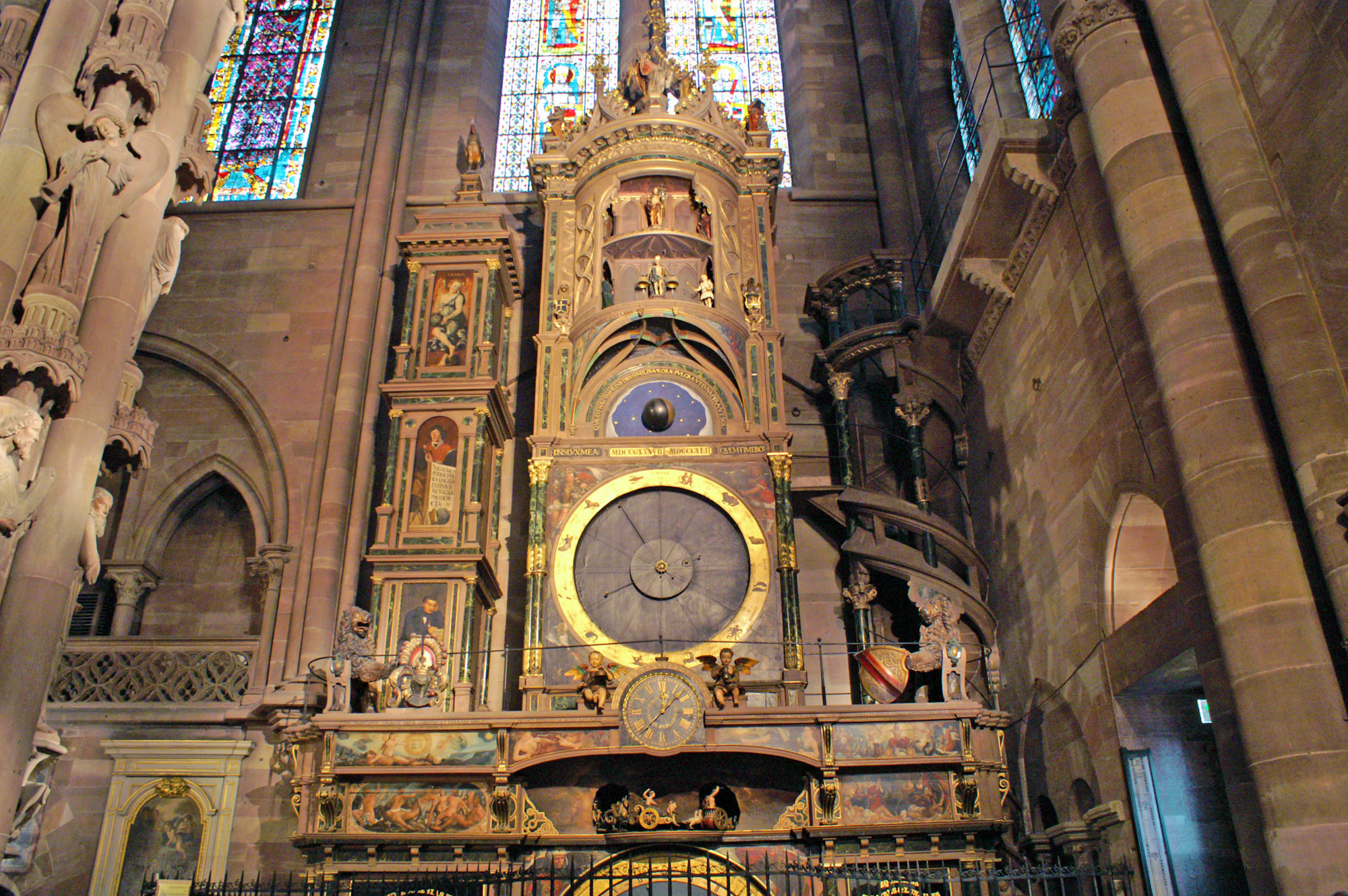

In eastern France

About 300 miles (482 km) east of Paris is the Cathédrale Notre-Dame in Strasbourg. This is home to one of the most beautiful and complicated astronomical clocks in Europe. The trip from the French capital by train takes less than two hours, and it’s totally worth it.

The current clock, which towers 59 feet (18 m) above the floor, is the third to grace the cathedral. The first clock was built in the 14th century. Little is known about this medieval clock other than it had a mechanical rooster that announced the hours. A second clock was built in the 16th century. It was adorned with an astrolabe dial, a Moon phase indicator, and calendar dials. It could even predict eclipses.

The third clock was finished in 1845 and is a marvel of astronomical complications. A large celestial globe sits at the base of the clock. Behind the globe, a massive dial shows apparent time while a statue of the goddess Diana points to liturgical events on a rotating ring with a golden arrow. As with many astronomical clocks, Moon phases are tracked, the Sun’s location along the zodiac is shown, and a perpetual calendar provides the current date. A great deal of additional information is displayed on multiple brass dials. Best of all, there is still an automated rooster.

The all-important Moon

Not all astronomical clocks are found on the walls and towers of cathedrals or housed in massive cases. The common grandfather clock is an astronomical clock that can provide celestial information.

While the clocks of Rasmus Sørnes have hundreds of gears, most grandfather clocks only boast 20 or 30 — yet this is sufficient to provide hours, minutes, and seconds, along with chimes that strike every 15 minutes. At the top of the clock face, a rotating dial shows our Moon, tracking the phases of Earth’s companion. Today, this little smiling Moon is mostly ornamental. For centuries, however, it served farmers by telling them when to plant their beans or the best time to go fishing.

Many pocket watches were also fitted with Moon phase dials. As with the grandfather clock, this requires an additional gear with 30 teeth linked to the drive gears of the clock or watch. This dial takes a month to rotate once but needs periodic adjusting to account for the Moon’s 29.5-day cycle. Some high-end mechanical wristwatches also capture the Moon’s movement with tiny dials. A few watch companies even make replicas of these medieval clocks for your wrist. All you need to own one is deep financial pockets.

Many grandfather clocks incorporate a Moon phase dial. Credit: Yaroslavl Art Museum/Wikimedia Commons

If you’re visiting Norway

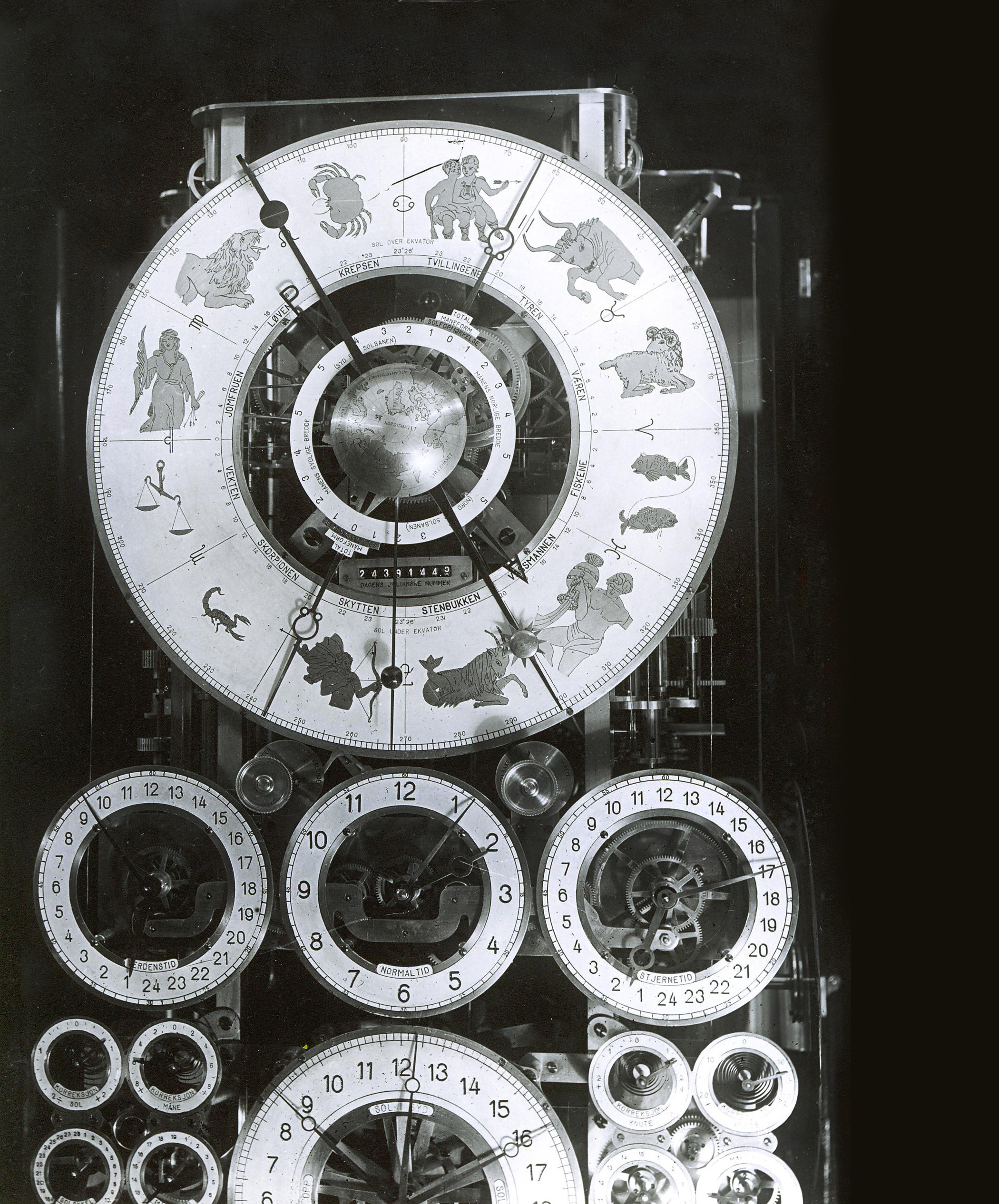

Medieval astronomical clocks were complicated and ingenious devices, but pale in comparison to the celestial clocks made by Rasmus Jonassen Sørnes, who began life as a Norwegian farmboy. As a teenager in the early 1900s, Sørnes applied to become an apprentice clockmaker but was turned down because he had big farmer’s hands. He eventually became a radio technician but never lost his love for horology.

Shortly before World War II, he began work on a series of astronomical clocks that combined traditional clock-making techniques with 20th-century technology. His first two clocks appear to have been test runs. Clock No. 3, however, is a masterpiece. A terrestrial and celestial globe are housed at the bottom of a glass and brass case. The terrestrial globe not only revolves once a day but also simulates the precession of the equinox. The stars on the celestial globe are represented by tiny holes lit by an interior lightbulb.

The main dial is engraved with the zodiac constellations. The Sun hand on this dial takes a year to revolve once, while the Moon hand has gears that allow it to speed through the zodiac in a synodic period of 29½ days. This dial also tracks the 18.5-year saros cycle to predict solar and lunar eclipses. (See page 53 for an explanation of the saros cycle.) The clock has 14 additional dials that show calendar dates, local and sidereal time, and a lot more. Sørnes even put a tape recorder in the base of the clock with a narrated presentation about astronomy. You can find the clock in the Borgarsyssel Museum in Sarpsborg, Norway, which lies around 57 miles (91 km) south of Oslo.

In 1966, Sørnes completed a fourth astronomical clock that was even more complex. This was an amazing feat for a self-educated man. Building mechanical clocks of this complexity requires understanding of mathematics, gear ratios, machining and electronics, and astronomy. Almost unknown today, Sørnes may be the greatest maker of astronomical clocks in history. Unfortunately, you can’t visit this horological wonder. After being displayed at the Time Museum in Rockford, Illinois, from 1967 to 1999, and at the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry from 1999 to 2002, the clock was acquired by an anonymous buyer. Its location is now unknown.

Time to begin

Today’s atomic clocks boast an uncertainty of one second in 300 million years. When you look at their numerical readouts, they tell you the exact moment you are in. What such clocks don’t provide can be found on a clock with a dial and hands. Such historical creations show us the astronomical rhythms of nature. These old clocks tell us the time it is now and the time that has slipped away, and point to the future that awaits us. I hope you’ll be able to visit one or more soon.