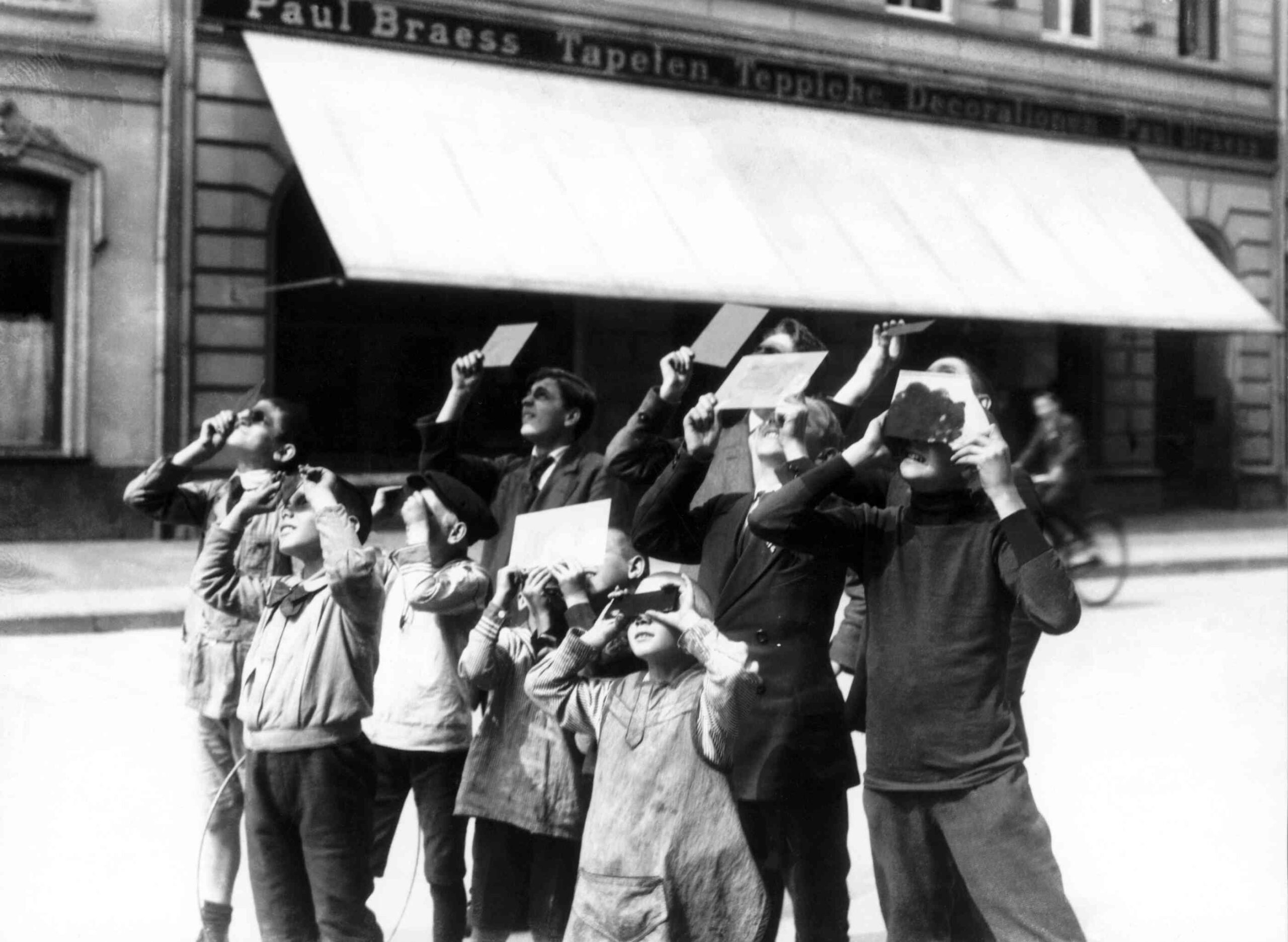

On Aug. 21, 1914, a total solar eclipse over Europe on the eve of World War I drew much attention. Albert Einstein had been waiting for an eclipse to verify his theory of relativity – specifically the light-bending effects of gravity – and enlisted help from Erwin Findlay-Freundlich of Berlin Observatory. Findlay-Freundlich was to lead a German expedition to Crimea, but the Aug. 2 declaration of war between Germany and Russia led to their entire research party being arrested, their equipment seized, and members either deported or held as prisoners of war. Other expeditions with similar goals, including an Argentine group and an American team from Lick Observatory, made it to Russia but faced poor weather; the trip home was also fraught, with the Americans fleeing through the Baltics to avoid the front. A British expedition was rerouted away from Kyiv (two team members were Jesuit priests, barred from entering Russia), but found more success in Sweden, with clear and detailed photographs being captured. However, they too faced a dangerous trip home, even requiring escorts to safely travel through minefields. Stymied by weather and war, none of the teams captured the evidence needed to support Einstein’s theory; it would remain unproven until Arthur Eddington’s 1919 eclipse expedition.