Sky This Week is brought to you in part by Celestron.

Friday, June 6

The Moon passes 0.5° south of the magnitude 1.0 star Spica at 11 A.M. EDT. The pair hangs in the evening sky, located in the south two hours after sunset. They are now some 6.3° apart, with the waxing Moon to Spica’s lower left.

Now draw a line between the two and continue following it to the lower left, toward the horizon. The next bright star you will land on, some 18° high, is bright red Antares, the heart of Scorpius the Scorpion. Shining at magnitude 1.1, it should look roughly as bright as Spica, albeit much redder. That’s because Spica is a younger, hot blue-white star; Antares is an older, cool red giant start in the latter stages of its life.

If you’ve got binoculars or a telescope, center the view on Antares and then move your gaze just 1.3° west — you may not need to physically slide your optics at all, as our target might already sit within your field of view: the globular cluster M4. Shining at magnitude 5.6, this aged group of stars is one of the closest globulars to Earth, roughly 7,200 light-years away. Its stars span some 36’ on the sky, a little larger than the area covered by the Full Moon. It makes a lovely sight, particularly given its proximity to Antares.

The Moon will pass close to Antares later this week, so we’ll make sure to stop back in this region in a few days to take in that sight.

Sunrise: 5:32 A.M.

Sunset: 8:26 P.M.

Moonrise: 4:22 P.M.

Moonset: 2:38 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (82%)

*Times for sunrise, sunset, moonrise, and moonset are given in local time from 40° N 90° W. The Moon’s illumination is given at 12 P.M. local time from the same location.

Saturday, June 7

The Moon reaches apogee at 6:44 A.M. EDT. This is when the Moon is at its farthest point from Earth in its orbit; this morning, our satellite will be 251,999 miles (405,553 km) away.

If you’re in the market for some deep-sky observing, early morning is your time. There’s a short dark window of about an hour after the Moon sets and before twilight begins to brighten the sky.

This morning, we’re enjoying one of the most famous planetary nebulae in the sky: M27, the Dumbbell Nebula. Shining at magnitude 7.4 and stretching some 8’ by 6’, this was the first planetary nebula ever discovered. Its common name is derived from its distinctly elongated, bi-lobed shape, which to visual observers appears narrower in the center and rounder at each end (like a dumbbell or bow tie). Deeper astrophotos, however, show that the nebula has a spherical shell in addition to its brighter, bow tie-shaped component.

You can spot M27 with either binoculars or a telescope. Start by looking south around 3:30 A.M. local daylight time, where Aquila the Eagle flies high in the sky, anchored by its brightest star, Altair. From Altair, slide your gaze nearly 11° north to land on magnitude 3.5 Gamma (γ) Sagittae. From this star, it’s a short 3.2° jaunt further northward again to find the Dumbbell. Astronomy contributing editor Phil Harrington recommends that if you’re using a telescope, employ a low-power eyepiece to first find the Dumbbell, then drop in a higher-powered eyepiece to explore its detail. Additionally, observers with larger scopes (10 inches or more) can try for the nebula’s central white dwarf, which shines at 13th magnitude.

Sunrise: 5:32 A.M.

Sunset: 8:27 P.M.

Moonrise: 5:24 P.M.

Moonset: 3:00 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (88%)

Sunday, June 8

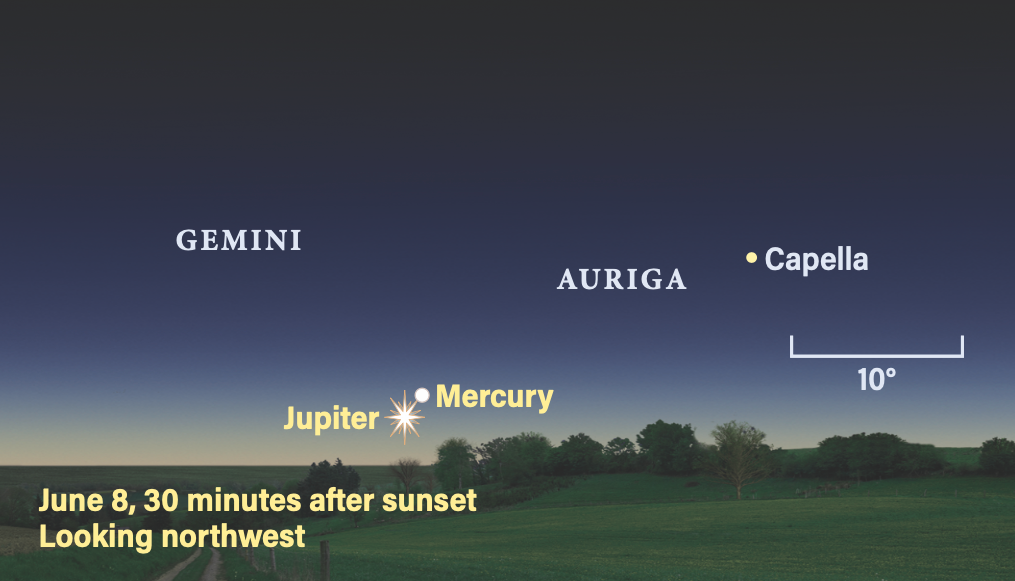

Jupiter is getting lower and lower in the evening sky; soon it will be lost from view as it heads for conjunction with the Sun.

But first, the solar system’s largest planet is teaming up with our smallest world: Today, these two worlds are in conjunction as Mercury passes 2° north of Jupiter at 4 P.M. EDT.

You can catch them together in the evening twilight, sinking in the west after sunset. But be quick: They are just a few degrees above the horizon half an hour after sunset. If you can get to a location with a clear western horizon, you’ll have the best chance of the longest view before the gas giant slips out of sight.

Mercury, shining at magnitude –1.3, stands just to Jupiter’s upper right. The gas giant shines at magnitude –1.9, only slightly brighter. Both will fit well inside the field of view of binoculars and may also stand together in a wide-field telescope eyepiece or your finder scope. Take care not to pull out any optics for use until the Sun has fully set from your location, which may differ from the time given below.

Take a look at each planet in turn. Mercury, physically much smaller but closer to Earth, shows off a disk that’s 5” wide and 89 percent lit. Jupiter is fully lit and appears 32” wide — a testament to its truly massive size, despite its greater distance. Mercury is currently some 116 billion miles (187 billion km) from Earth, while Jupiter is nearly 570 billion miles (917 billion km) distant.

Although Jupiter is flanked by its four Galilean moons, they will be difficult to make out in the brightening sky. The planet’s Great Red Spot is also transiting this morning and may be visible for those with particularly steady seeing.

Sunrise: 5:31 A.M.

Sunset: 8:27 P.M.

Moonrise: 6:26 P.M.

Moonset: 3:25 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (94%)

Monday, June 9

The constellation Hercules is high in the east after dark this evening. Rich with deep-sky objects, we’re passing by the Strongman’s most famous (M13) for its second-brightest globular cluster: M92.

But don’t feel like you’re settling for second best: This cluster is only a little fainter and smaller than M13, so it’s a stunning sight in its own right.

Shining at magnitude 6.4, you’ll find M92 about 6.3° north of magnitude 3.2 Pi (π) Herculis, one of the four stars in the Keystone asterism. Spanning about 14’, M92 is a dense ball of aging stars that lies nearly 27,000 light-years away and is an estimated 14 billion years old. Although visible to the naked eye under good conditions, the bright moonlight pervading the sky tonight will likely make M92 a binocular or telescope object only. However, one benefit of this bright cluster is that no matter your optics, it should look stunning. Note particularly its dense, compact core, and don’t be afraid to bump up the power in your telescope when viewing it.

Sunrise: 5:31 A.M.

Sunset: 8:28 P.M.

Moonrise: 7:30 P.M.

Moonset: 3:54 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (97%)

Tuesday, June 10

The Moon now passes 0.3° south of Antares at 7 A.M. EDT. You can catch them early this morning, when they are highest in the south just after midnight on the 9th. The Moon’s bright light dominates the southern sky as our satellite quickly waxes toward the Full phase, which it will reach in just over 24 hours.

Early this morning you’ll see the Moon just to the lower right of Antares. The Scorpion’s alpha star shines at magnitude 1.1 and should remain visible even in the moonlight. It shows off a notable red hue, thanks to its relatively cool surface temperature of 6,000 F (3,300 C).

Spica, the 1st-magnitude star in Virgo that the Moon passed by late last week, is now far to the pair’s upper right.

Look carefully for the long, curving tail of Scorpius to the pair’s lower left, closer to the horizon. Shaula (Lambda [λ] Scorpii), which shines at magnitude 1.6, is the brighter of two stars in Scorpius’ stinger — you may be able to spot this star relatively well.

Sunrise: 5:31 A.M.

Sunset: 8:28 P.M.

Moonrise: 8:30 P.M.

Moonset: 4:31 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (99%)

Wednesday, June 11

Full Moon occurs this morning at 3:44 A.M. EDT. Early risers can catch the Moon setting in the southwest shortly before sunrise, while anyone out in the evening will see the Full Moon rising again in the southeast not long after the Sun has set. That’s because the Full Moon is always located opposite the Sun in our sky, rising around sunset and setting around sunrise.

June’s Full Moon is also called the Strawberry Moon, but don’t let the name fool you — it won’t be turning pink in the sky! The moniker comes from several Native American tribes, who named it for the fact that June in North America is the time when early strawberries are often ripe for picking.

You may also notice that the Full Moon arcs low through the southern sky tonight, rather than soaring high overhead as it sometimes seems to do. That’s because we’re getting close to the summer solstice in the Northern Hemisphere, when the Sun is highest in the sky. The Full Moon around this time is generally the lowest we see all year. At its highest point overnight tonight, when the Moon hangs just off the spout of Sagittarius’ Teapot in the south, it will only reach an altitude of roughly 20° above the horizon from the mid-U.S. Note that it may climb higher or lower depending on your location (more specifically, your latitude).

Sunrise: 5:31 A.M.

Sunset: 8:29 P.M.

Moonrise: 9:27 P.M.

Moonset: 5:16 A.M.

Moon Phase: Full

Thursday, June 12

Saturn’s two-faced moon Iapetus reaches its greatest western elongation today. At western elongation, the moon’s lighter hemisphere is turned toward Earth, making it brightest and easiest to view through a telescope.

First, locate Saturn above the eastern horizon around 4 A.M. local daylight time, roughly 90 minutes before sunrise. At this time, the planet should be high enough (25°) that it’s not too affected by the turbulent air close to the horizon, but the sky should also be dark enough to allow you to pull Iapetus out from the background. Saturn itself shines at magnitude 1.0, hanging beneath the Circlet of Pisces and to the far upper right of blazing Venus, which lies closer to the ground and shines a brighter magnitude –4.3.

Once your telescope is locked on Saturn, you’ll likely notice its biggest and brightest moon, 9th-magnitude Titan, sitting about 3’ east of the ringed planet. Iapetus, one magnitude fainter, lies on the other side of the world, some 8.5’ to Saturn’s west. Several 10th-magnitude moons cluster closer to the rings as well — Dione and Rhea lie just west of the planet, less than about 1’ away. Tethys may be visible to the west of the planet for some East Coast observers as well, but it’s moving into Saturn’s shadow and then behind the planet in an occultation for most U.S. observers.

Sunrise: 5:31 A.M.

Sunset: 8:29 P.M.

Moonrise: 10:17 P.M.

Moonset: 6:09 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waning gibbous (98%)

Friday, June 13

Mercury has brightened a bit and now shines at magnitude –0.8 in the evening sky, lingering above the horizon some 80 minutes after the Sun disappears. Tonight, the solar system’s smallest planet stands just 20′ from the 3rd-magnitude star Mebsuta (Epsilon [ε] Geminorum), near the middle of the constellation Gemini.

You can catch the pairing with binoculars or a small scope shortly after sunset. Try looking west about 45 minutes after the Sun disappears — the two points of light will then be roughly 5° high at that time. Through a telescope, you’ll also be able to see that Mercury’s 6”-wide disk is 78 percent lit. Compared to earlier this week, it’s 1” larger but a few percent slimmer in terms of illumination.

About 13° above Mercury is Castor, Gemini’s alpha star and one of the Twins’ two heads. Shining at magnitude 1.6, Castor is slightly fainter than Gemini’s beta star, magnitude 1.2 Pollux, which lies about 4.5° to its left as the constellation sets this evening. Compare the colors of these two stars through your optics: Pollux should appear more golden yellow than Castor, which appears more blue-white. Additionally, Castor is an easy-to-split multiple-star system. Its two brightest components, which shine at 2nd and 3rd magnitude, lie a few arcseconds apart. Farther away, some 1.2’ south of this pair, is a third star, shining at 9th magnitude.

Each of these three stars is a binary system as well, although none can be further split by a telescope.

Sunrise: 5:31 A.M.

Sunset: 8:30 P.M.

Moonrise: 10:59 P.M.

Moonset: 7:11 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waning gibbous (94%)