Why don’t planets fall into the stars they orbit if they’re constantly being pulled by gravity?

Lindsey Coughter

Rocky Mount, North Carolina

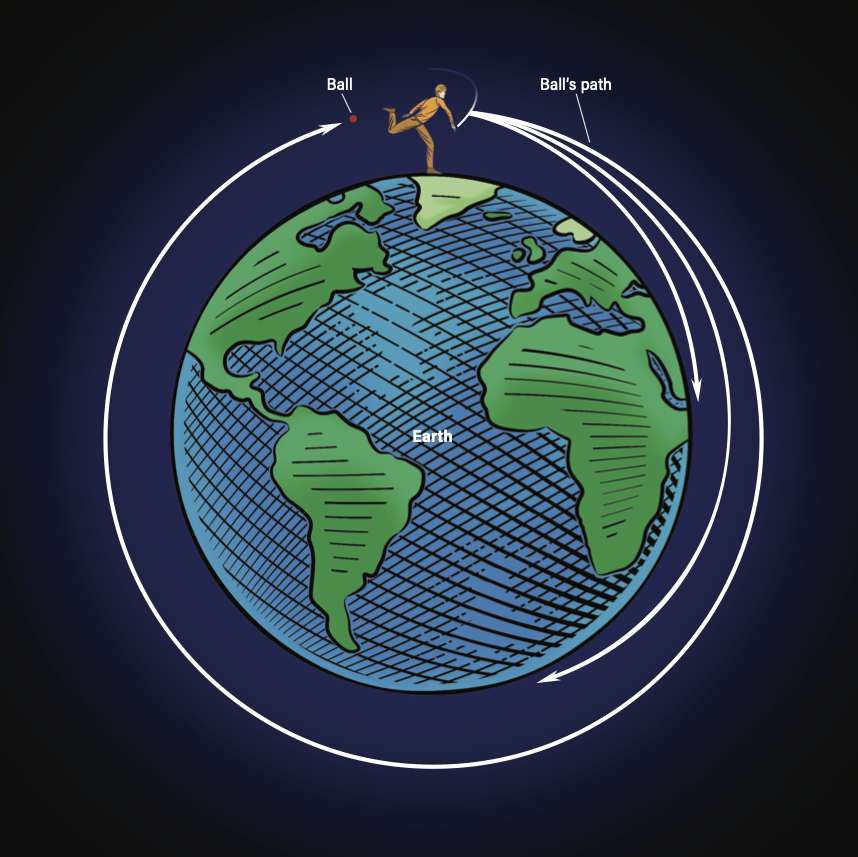

This is a brilliant question because the notion of an orbit is counterintuitive. We know that massive objects (really, any objects with mass) gravitationally attract other massive objects; Newton’s law of universal gravitation is firmly established on this point. For instance, throw a baseball horizontally at about shoulder height and it will follow a curved path until it strikes the ground because Earth quickly draws the ball back to its surface. (Technically, Earth and the ball move toward each other and collide, but Earth is so much more massive than the ball that the former’s motion is practically zero.)

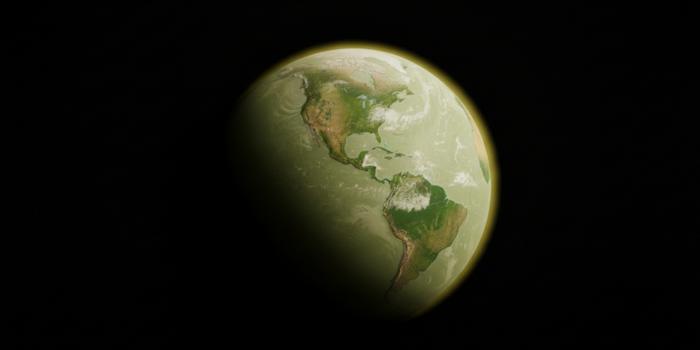

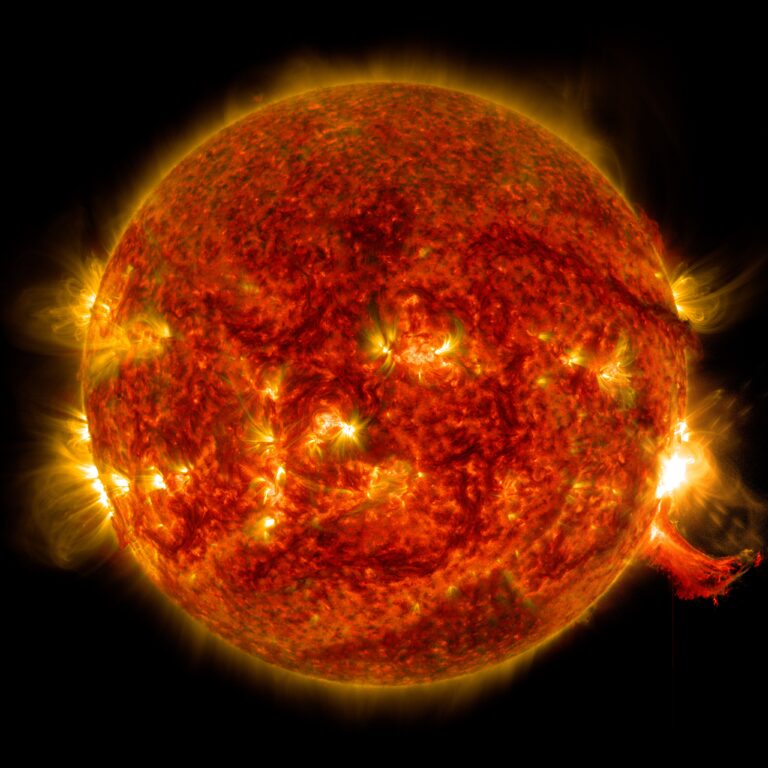

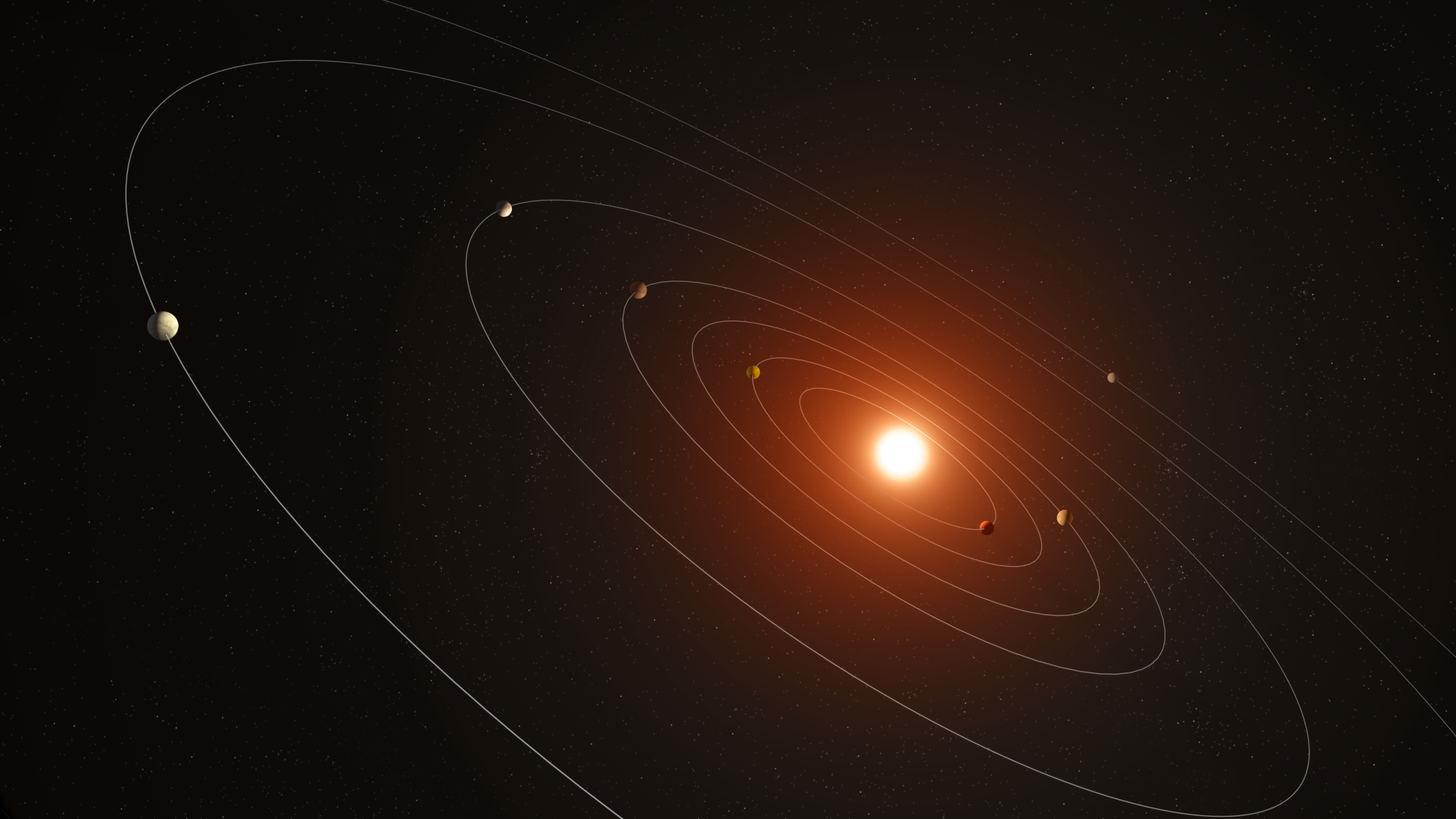

A star and attendant planet, both being massive, should also come together rapidly. Instead, planets tend to maintain orbits around stars without actually crashing into them.

To understand how planets are able to maintain a respectful distance from their parent stars, let’s return to the aforementioned baseball. Earlier, we imagined throwing it at normal human strength. Now, imagine you throw it again, but at a much higher velocity. The baseball still falls to the ground, but it takes longer — the parabolic path it follows is longer, due to its increased horizontal speed. Continue throwing the ball at ever-increasing velocities and the descending path the ball follows becomes increasingly longer. Finally, imagine that you are able to throw the ball so fast that the surface of Earth curves away from the ball’s path faster than the ball can fall. As a result, the ball’s curved path carries it around Earth. The ball wouldn’t ever strike the ground but would constantly miss it altogether and continue falling — and end up orbiting the planet.

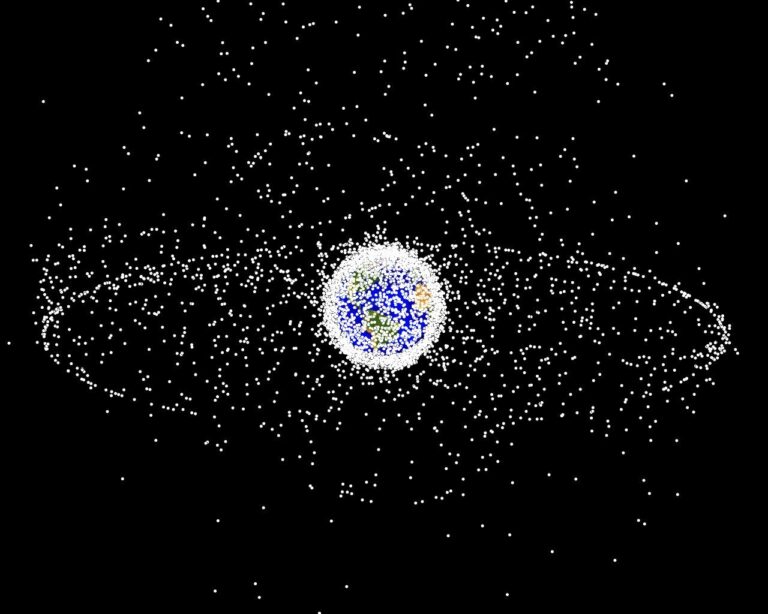

The problem with this picture, apart from the fact that nobody can throw a ball that fast, is that atmospheric drag would quickly reduce the ball’s speed and cause it to strike the ground. Many artificial satellites moving around Earth, including the International Space Station, experience this atmospheric drag, albeit to a lesser extent due to the reduced particle density at such high altitudes. (As a result, these objects all eventually crash back to Earth unless they are boosted up again.)

A planet, on the other hand, is essentially moving through a vacuum, and so no reduction of its velocity will occur. The planets are moving fast enough and at a great enough distance that as they “fall toward” the Sun, the Sun will never actually intersect with their orbital path.

To paraphrase the late Douglas Adams, “The knack of flying is learning how to throw yourself at the ground and miss.” Orbits operate on essentially the same principle.

Edward Herrick-Gleason

Astronomy Educator, St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador