Key Takeaways:

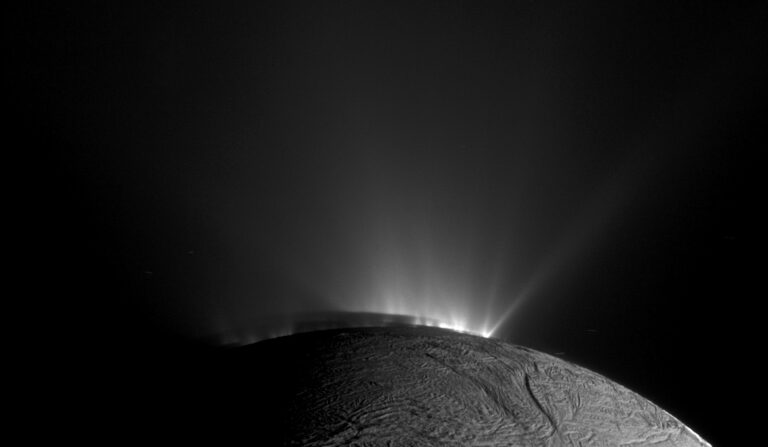

- The hexagon-shaped cloud pattern at Saturn's north pole, initially observed by the Voyager spacecraft and subsequently studied by Hubble and Cassini, is a persistent atmospheric feature that has endured for decades.

- Its long-term stability indicates that the hexagon is neither a transient seasonal phenomenon nor solely attributable to short-lived atmospheric storm systems.

- New laboratory fluid-dynamics research, comparing models to Saturn observations, proposes that steep contrasts in wind speed within Saturn's northern jet stream generate unstable behavior in the fluid.

- This instability is hypothesized to create six standing waves that encircle the planet at the same propagation speed as the jet, thereby forming and maintaining the hexagon's geometric structure and apparent stationary nature.

Interestingly enough, the hexagon has persisted over decades, and the Hubble Space Telescope and most recently the Cassini spacecraft have studied it. Because this feature hasn’t disappeared indicates that it cannot result from the change in seasons; Saturn’s seasons last approximately seven Earth years, so we would have seen the hexagon vary. Some have theorized that the hexagon is a standing wave in Saturn’s atmosphere, or that a storm just south of the hexagon (observed during the Voyager era) was the driving force. However, that storm died out while the hexagon has not.

Ana Aguiar and colleagues at the University of Oxford have, for the first time, arrived at a working laboratory model that produces a six-sided structure. Aguiar’s team compared fluid-dynamics research to Saturn observations to find that the steep changes in wind speeds within Saturn’s northern region could create unstable behavior in a fluid. Saturn’s north polar area has a jet stream, which moves at a specific speed. Strong contrasts in wind speeds can create a wavelike motion of that jet in the atmosphere; six waves encircling the planet along with the jet would produce a hexagonal structure.

The hexagon appears stationary in relation to Saturn’s atmosphere because the waves move at the same speed that the jet propagates. This goes to show that you never know what you can do with a spinning tank of water in a lab!

University of Maryland,

College Park