Plumes spouting from Saturn’s moon Enceladus provide a tantalizing glimpse of the ocean beneath, a potentially habitable region where life may have evolved. Light and dark swaths of the moon reveal information about the material as it falls to the surface. By studying the discolorations on the crust, scientists hope to learn more about watery realm underneath.

While the most massive particles fall directly back onto the surface, lighter ones leave the moon entirely, creating Saturn’s thin E-ring. Radiation converts the material from its original pristine form into something else, a darker, chunkier material that eventually falls back onto Enceladus as the moon plows through it.

“It’s clear that the E-ring grains are a different color in the visible [spectrum] than the plume grain regions,” says Amanda Hendrix, of the Planetary Science Institute in Colorado. By studying the different grains with Cassini’s Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph (UVIS), Hendrix hopes to narrow down the ingredients coming from the plumes. She presented her research in Octoberat the annual Division for Planetary Sciences meeting in Pasadena, California.

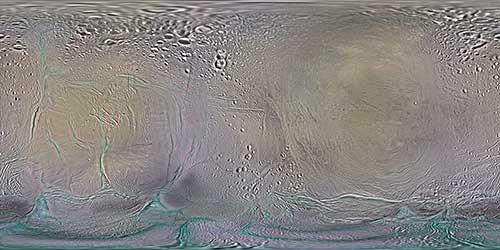

Bands of light and dark

Enceladus was considered a dead icy world until NASA’s Cassini mission arrived. In 2006, it spotted a fountain of material erupting from the moon’s southern pole. Later observations by the spacecraft revealed that an ocean, rather than a localized lake, existed beneath the surface of the moon.

Cassini had no plans for analyzing particles erupting from a planet, but that didn’t stop its engineers from repurposing an existing instrument for the task. Since it spotted the plumes, the spacecraft made multiple dives through the spouts, concluding its final trip in October 2015. Still, the revised instrument could only go so far in analyzing the organic material.

To learn more about the interior of Enceladus, Hendrix is studying the material on its crust. By examining differences in how the material is changed by its time in space, she hopes to better understand its original condition.

“All of those E-ring grains coat the surface of Enceladus,” Hendrix says. While a lot of it escapes into space, the majority of them fall back onto the surface. “You wind up with these visible color variations,” she said.

Previous models of the plumes suggested that while some of the material that immediately crashes back to the surface can coat the northern hemisphere and equatorial regions, most of it lands around the south pole. The discoloration supports that idea as it reveals lighter, unprocessed material dense around the southern pole and thinning out farther north.

In a 3-color images, the plume fallout appears bluish, while material from the E-rings are yellower, Hendrix says. This helps scientists to identify the different sources. While in space, radiation processes the particles, making them chunkier as the smooth profile of the fine ice grains becomes rougher.

Most of the material falling back to the surface is salt-rich, Hendrix says, a contrast to the salt-free E-ring. That’s because the salts are too massive to break free from the moon’s gravity and join the ring. Hendrix and her colleagues also identified differences in the organic content, most likely due to the amount of processing that occurs in space.

“It may be that the plume fallout zones contain just as much organic material but it hasn’t been processed as much, because it hasn’t spent as much time in the E-ring,” she said.

A reddish moon

Enceladus isn’t the only moon that captures in-falling material. The splotchy reddish moon Tethys lacks the geysers of its sibling satellite but still winds up covered as it interacts with the ring. Because it is tidally locked, with one face permanently turned toward Saturn (as all of Saturn’s moons are), one side captures the brunt of the material while the other side remains relatively bare.

“I think Tethys is in the sweet spot,” Hendrix says.

The material that lands on its surface looks different from the particles falling on Enceladus, where the returning particles are soon covered by plume material. Because Tethys lacks plumes, radiation continues processing the icy material that falls to the surface into something else. “They’re almost like tholins,” Hendrix says.

Tholin is something of a catch-all term for the material created when simple organics undergo radiation. Tholins are suspected to cause the reddish spot on Pluto’s moon, Charon, and are thought to exist on other moons like Saturn’s Titan.

“It’s probably not proper tholins, but some complex organics,” Hendrix says.

While tholins are gunky, the particles on Tethys are probably icier than their Charon counterparts.

By probing the mysteries of the plume material on multiple moons, Hendrix and her colleagues hope to understand more about the potentially habitable ocean beneath the surface of Enceladus.

Further reading:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/2015/0722-what-in-the-worlds-are-tholins.html