Scientists have had evidence for a while that the Milky Way saw a major merger in its past. Even without direct evidence here in our home galaxy, scientists know that galaxy collisions are commonplace in the universe. These mergers are the major way that galaxies grow and evolve. But this is the first time that astronomers have been able to pinpoint the ages of different stellar populations within the Milky Way accurately enough to pin down when this merger occurred, and how exactly it affected our home galaxy. Researchers led by Carme Gallart from the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias in Spain published their findings Monday in Nature Astronomy.

Galaxies Collide

To read the Milky Way’s history, astronomers must pinpoint the ages of different populations and groups of stars within the galaxy. This is tricky because measuring stars’ ages is an inexact science. Scientists can’t really just look at a star and tell its age, even with detailed measurements. Instead, they look at batches of stars and compare them to model star populations. Stars are typically born in large litters, and by getting details about whole groups of stars, scientists can run the clock backward and get a more accurate picture of when that birth occurred

And thanks to the outpouring of new data from the Gaia mission, which is creating the most accurate stellar map yet, astronomers were able to take a big step forward in this challenge.

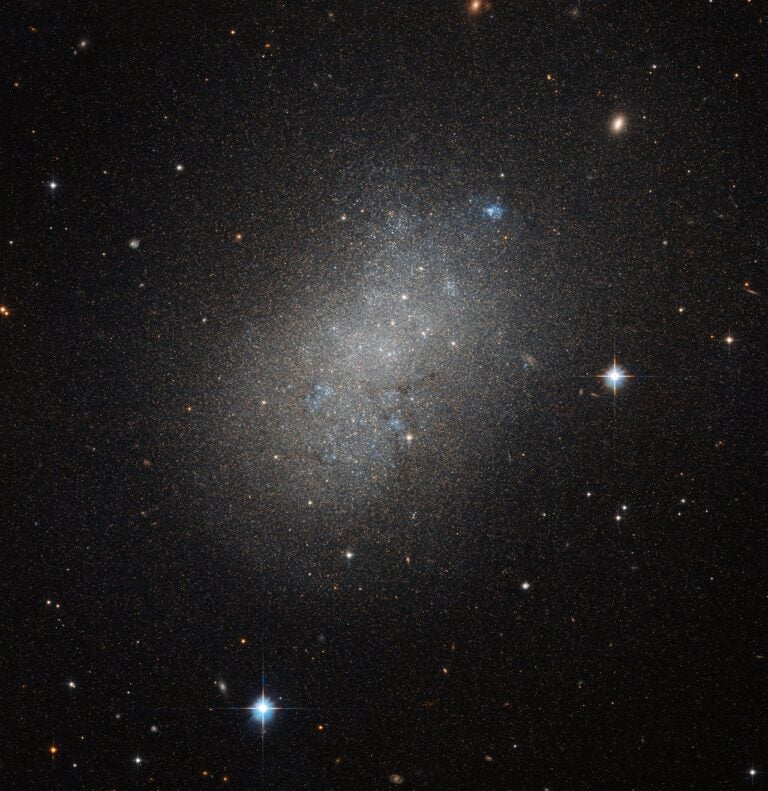

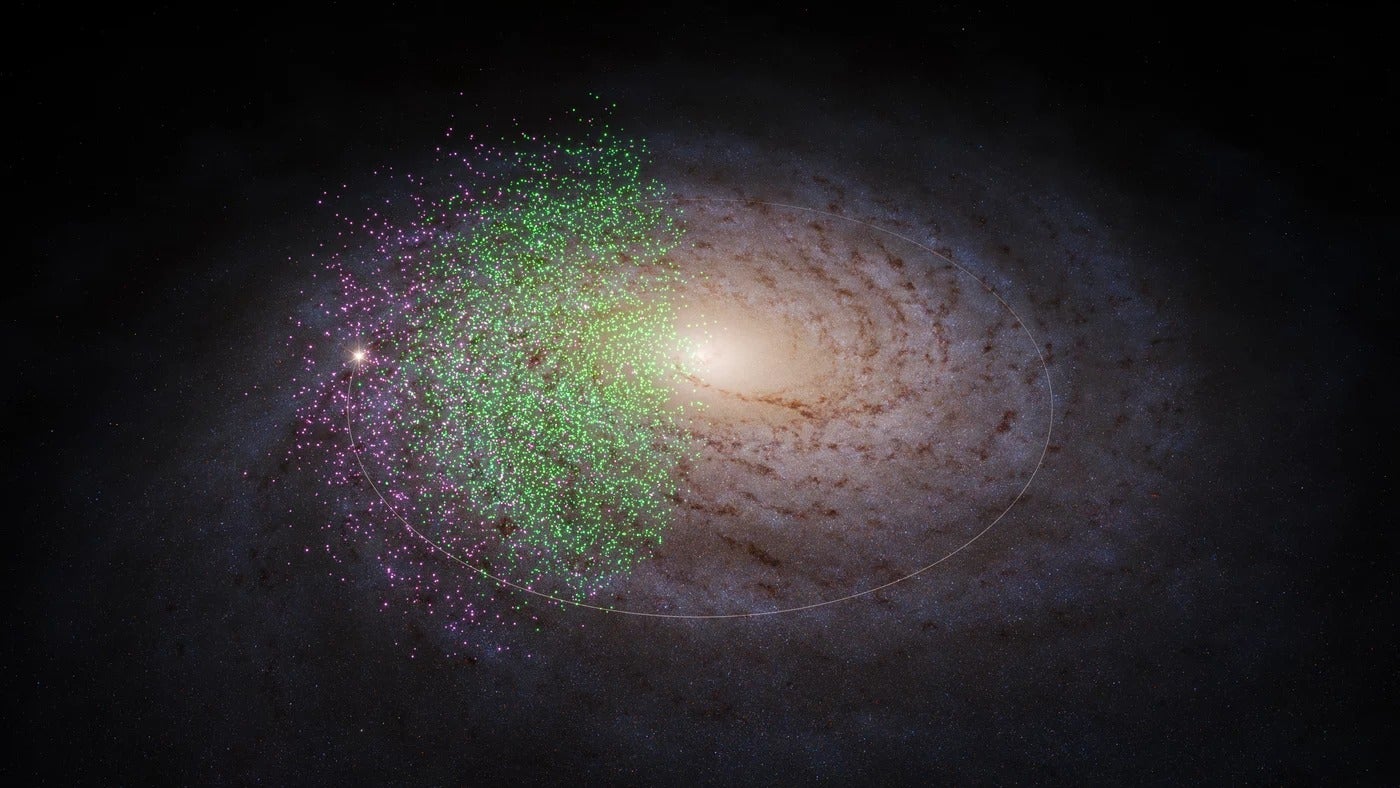

Armed with their new data, astronomers plotted stars from similar regions of the Milky Way. They discovered two distinct populations of stars. Some stars, which appear redder in color, appear to have formed in a larger, more metal-rich galaxy. (It’s worth remembering here that astronomers call any element not hydrogen or helium a “metal.”) The other, bluer population of stars should have formed in a smaller, more metal-poor galaxy. The fact that astronomers see these populations mixed together is a sign that the larger galaxy (the early Milky Way) encountered and consumed a smaller galaxy (Gaia-Enceladus) at some point in the past.

Astronomers had suspected such an event based on previous observations, but the new Gaia data lends more clarity. The data also back up what astronomers had suspected, that the interloper galaxy was roughly a quarter the size of the original Milky Way.

The timeline of this event was under debate, however. But the new data allowed astronomers to measure that ages of stars in the Milky Way’s halo, a sort of bubble of stars rising above and below the more familiar disk shape, all cut off at 10 billion years ago. The reason these stars orbit out of the Milky Way’s disk is because they are moving faster than other stars, and the implication is that some energetic event tossed them to these high speeds.

By combining the ages of the stars with models of galaxy evolution, astronomers can paint a timeline of the Milky Way’s history. For some 3 billion years, the young Milky Way evolved on its own, until it ran into the smaller Gaia-Enceladus 10 billion years ago. This encounter tossed some stars into the halo, and also poured gas – the fuel for new star formation – into the Milky Way’s disk, causing a burst of new star formation. Over the next few billion years, this flurry of activity eased off, though our galaxy still has enough fuel to keep making stars at a decreased rate.

Thanks to the massive amount of data Gaia collects, scientists receive the findings on a delay. The current results are based only on the first 22 months of data, collected between 2014 and 2016. Gaia will keep collecting data until at least 2022, and probably 2024 if all continues smoothly. As the project continues to release new measurements, researchers’ understanding of our galaxy can only improve.