Despite being relatively easy reads, the two publications carried impressive titles: The Geography of the Heavens, or Familiar Instructions for Finding the Visible Stars and Constellations; Accompanied by a Celestial Atlas, with a View of the Solar System, Illustrated by Engravings and Atlas Designed to Illustrate Burritt’s Geography of the Heavens. Each cost $1.25 in 1833, a bit pricey for the textbook, but a steal for the atlas.

The set was a smash hit. In the 16th edition, published in 1876, the preface stated that more than 300,000 copies had been sold. That number makes it the most popular star atlas of the 19th century. In fact, it wasn’t surpassed in sales until the mid-20th century, after numerous editions of Arthur Philip Norton’s Star Atlas and Reference Handbook, first published in 1910, had appeared.

Who was Burritt?

Elijah Hinsdale Burritt (his middle name was his mother’s maiden name) was born April 20, 1794, in New Britain, Connecticut. He was the first of 10 children.

When he was 18, Burritt ventured to a nearby town to study for two years to become a blacksmith. Unfortunately, he suffered an accident. That, along with motivation from his friends, caused him to enroll in Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, where he studied astronomy, a subject he’d read a lot about during his recovery.

After a year, his finances forced him to take up a teaching job in 1817 to earn money to continue his studies. He then went back to college, but in 1819, he left to teach school (among other pursuits, including editing a weekly newspaper) in Milledgeville, Georgia. He remained there for 10 years before moving back to New Britain. While in Georgia, he married Ann Williams Watson, with whom he had five children.

Upon returning to Connecticut, he converted some property he owned, called the Stone Store, into a school. As part of the conversion, Burritt installed an observatory, featuring a telescope he had purchased, on the top floor.

Geography

Once back in Connecticut, Burritt began writing The Geography of the Heavens. He had one major book under his belt already, having authored Logarithmick Arithmetick in 1818. The first half of this work was a textbook on arithmetic. He followed it with a section on astronomy, and devoted the final 40 pages to a table of logarithms from 1 to 10,000, each calculated to seven decimal places. Burritt also included a method for students to calculate the logarithms of numbers up to 10 million.

In 1821, Burritt wrote a 28-page pamphlet: Astronomia, or directions for the ready finding of all the principal stars in the heavens which are named on Carey’s Celestial Globe. He followed this work in 1830 with another pamphlet that showed how to compute interest, both simple and compound.

The book that made Burritt famous, however, was The Geography of the Heavens. He wanted to call it Uranography, but his publisher (probably wisely) insisted on Geography. Apparently buying into this notion, Burritt writes in the preface that he wants the book to be to the heavens what geography is to Earth.

Burritt devotes the main part of the book to the constellations. He describes each star figure, recounts its mythology and history, and lists the brightest stars it contains, giving their magnitudes and other facts.

The next section deals with the solar system, followed by a number of problems for readers (mainly students) to solve, and then an appendix with 13 astronomical tables.

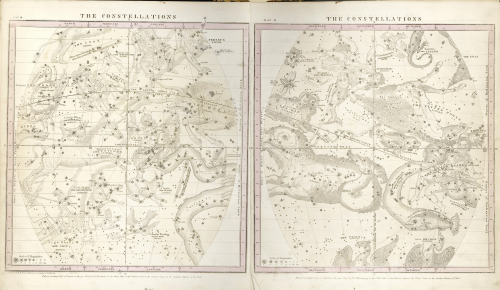

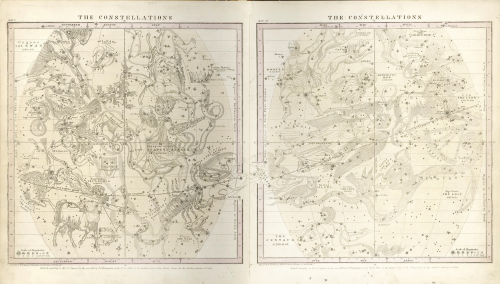

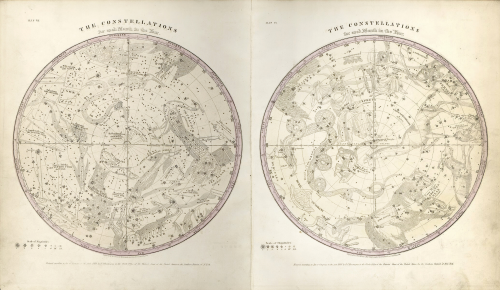

The Atlas contains seven maps. Four of them show constellations in the equatorial regions by season, two illustrate the star figures in the polar regions, and one is an all-sky chart that shows the Sun’s position on the ecliptic throughout the year. Burritt drew all the maps and supervised their engravings. But although he drew them, he didn’t create them — he copied all the constellation figures from English astronomer Francis Wollaston’s A portraiture of the heavens, as they appear to the naked eye: constructed for the use of students in astronomy, which appeared in 1811. Later editions of the Atlas included an additional spread showing the relative sizes and distances of the Sun, Moon, and planets, along with many other solar system facts.

Burritt also added material to the second (1835) and third (1836) editions of the textbook, but he died before further editions were printed. The next four editions (1841, 1844, 1846, and 1849) were reissues of the third edition. In 1852, American astronomer Hiram Mattison revised the Geography, and added two pages containing 80 drawings of double stars, comets, clusters, and nebulae to the Atlas. Mattison produced nine editions, the last one in 1876.

(Left): The final map (Map VII) in the Atlas displays the stars and constellations around the South Celestial Pole. Several defunct constellations are visible, including Robur Caroli and Solarium.(Right): Map VI in the Atlas displays the stars and constellations around the North Celestial Pole. Note the presence of the defunct constellation Quadrans Muralis (“Mural Quadrant” on the map). In its boundaries was the radiant of the Quadrantid meteor shower (thus the name). That point now lies in Boötes. Another now-defunct constellation is also present: Gloria Frederica.

Gone too soon

Burritt died January 3, 1838, in Galveston, Texas. Late in the previous year, he had organized and led a group of 30 colonists, which included one of his sisters and a brother, to Houston, Texas, to settle there. In 1836, Texas seceded from Mexico and became an independent republic. It wouldn’t become part of the U.S. until 1845. Burritt was drawn to Texas because the government had passed laws that granted colonists generous plots of land.

Burritt’s group chartered a ship and, after a 28-day voyage, landed at Galveston — well, sort of. A storm caused the ship to wreck on a sandbar, which delayed the actual landing by several days. The journey to Houston took just a few more days, but once they arrived, the party had to live in tents because nobody was expecting them. Within a week, yellow fever broke out and wiped out nearly the entire group, including Burritt, who died in Houston just a few weeks later.

Testimonials

I have owned a copy of the original 1833 edition of The Geography of the Heavens for many years, as well as a set of Burritt’s 1835 constellation maps, which I had framed in the 1980s. When I began collecting 19th-century first-edition astronomy books, this set was one of the top 10 items I set out to acquire. But I wasn’t the only one who thought highly of Burritt’s work.

The famous double-star discoverer Sherburne Wesley Burnham became interested in the stars after purchasing a copy of Burritt’s Geography at an auction in 1862 in New Orleans, where Burnham was a shorthand reporter in Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler’s Union Army headquarters. After studying the constellations shown in the Atlas, Burnham began to identify them in the sky. He held positions at several observatories and finished his career as an astronomer at Yerkes Observatory.

Praise also came from outside the field of astronomy. In a letter dated January 1, 1915, to Maurice Winter Moe, American horror author H.P. Lovecraft cited his admiration for Burritt’s work, a copy of which he inherited from his grandmother: “Her copy of Burritt’s Geography of the Heavens is today the most prized volume in my library.”

For the simplicity of the text, the beauty of the illustrations, and the sheer number of sales, The Geography of the Heavens is rightly hailed as a terrific teaching tool. Likewise, Elijah Hinsdale Burritt deserves his place as one of the great popularizers in the history of astronomy.