The next generation of exoplanet hunting has arrived in the form of NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet and Survey Satellite. TESS looks at closer and brighter stars than Kepler, the spacecraft that first turned the trickle of exoplanet discoveries into a deluge. While TESS, which launched last year, is just beginning its sky search, it’s already started discovering new planets. Astronomers say they’ve discovered an Earth-sized planet dubbed HD 21749 c that sits just 52 light-years from Earth and orbits its star every 8 days. It’s TESS’ first discovery of an Earth-sized planet.

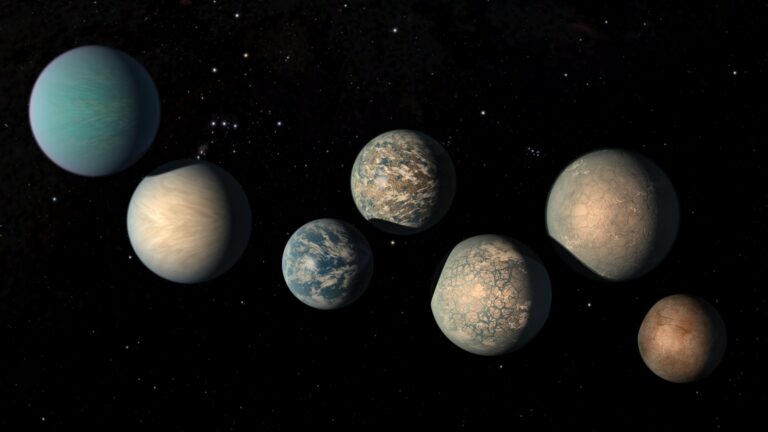

Scientists also say they’ve confirmed HD 21749 b, a planet a little smaller than Neptune on a roughly 35-day orbit around the same star. Both TESS exoplanet findings were teased earlier this year.

Transit hunting

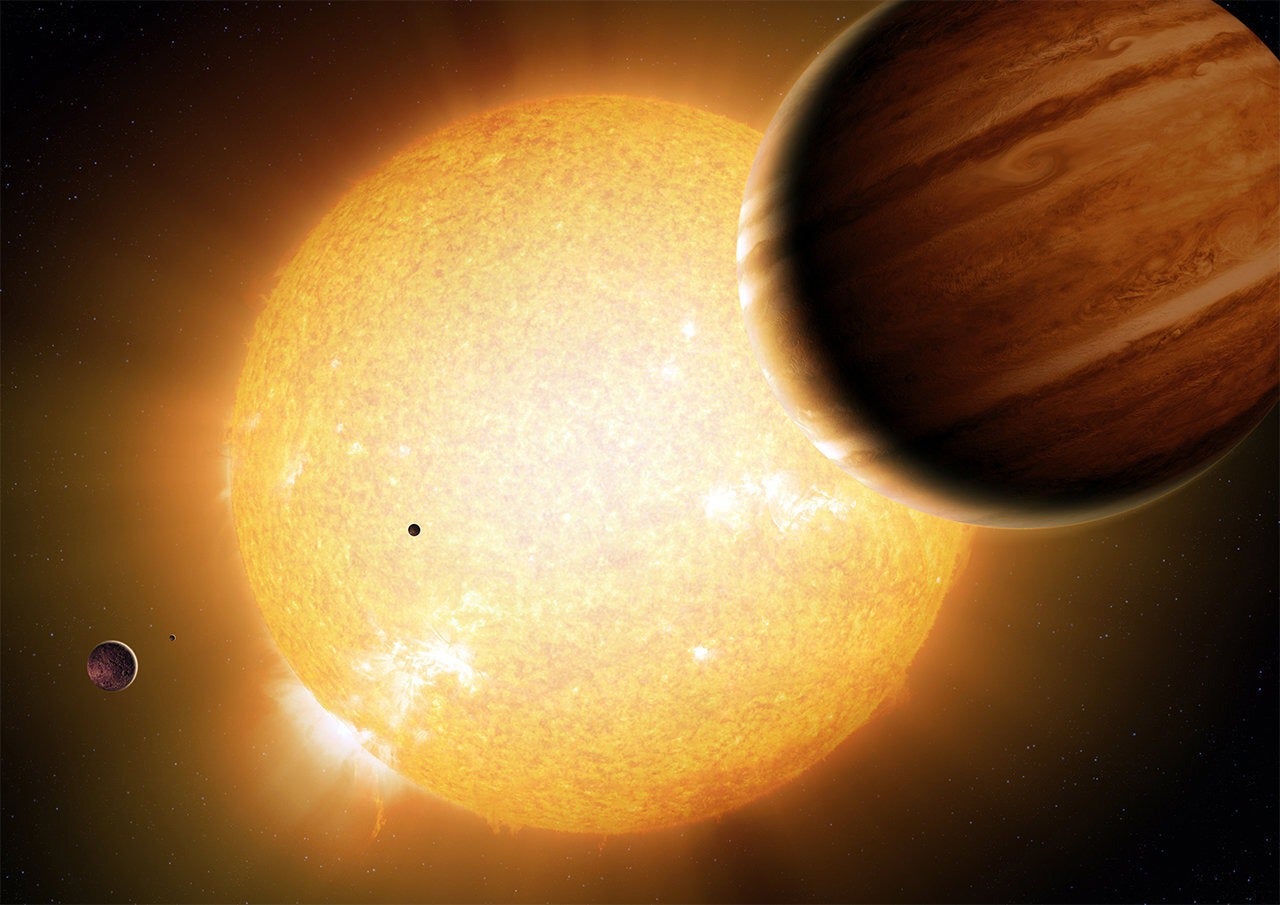

TESS searches for planets in the same basic way that Kepler did, by watching for planets to transit — or pass in front of their stars — from Earth’s point of view. But TESS will eventually study an area 400 times larger than Kepler’s corner of the sky, and it will focus on nearby, bright stars that will make for easier follow-up targeting by powerhouse observatories like the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope.

One of TESS’ main goals for its initial two-year mission is to find 50 planets that are no more than four times bigger than Earth and that have measured masses. This is a peculiar goal, because TESS can’t actually measure the masses of any planets — it can only determine how wide a planet is and how far from its star it orbits. Instead, TESS was designed to work with other observatories, like the two telescopes in Chile that provided radial velocity measurements to pin down the mass of HD 21749 b. Radial velocity is a way for astronomers to observe the tiny gravitational tug that a planet has on its star. Unlike transits, radial velocity does tell astronomers about the mass of planets. With both measurements, the telescopes can confirm each other’s findings and complement the information each reveals about the far-off worlds.

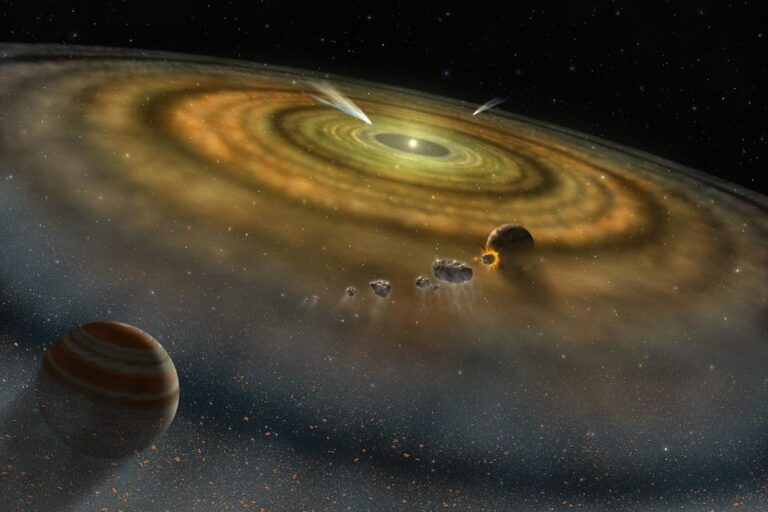

In this case, radial velocity hasn’t yet been able to pin down a mass on the smaller, Earth-sized planet in the system, because it probably only weighs a few times more than our own world. The larger planet is a hefty 23 Earth masses, showing up more clearly in the data. In fact, it’s rare to find such a large, dense planet. It’s also far from its star – most of the planets TESS finds will have orbits less than 10 days. HD 21749 b, orbiting every 35 days, is distant enough to be warm instead of hot. This makes it a fairly unique specimen that could tell astronomers a lot about how planets form. The discovery of both planets is announced Monday in Astrophysical Journal Letters, by teams from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Carnegie Institution for Science.

Johanna Teske, a co-author on the discovery paper, worked mostly on the radial velocity side of the research. In an interview, she said that the system was already part of a long-term survey, and that as data accumulates, they’ll get better constraints on the smaller planet, if not a precise measurement. “We’ll be continuing to monitor it, probably for many years,” she says.

She also points out that as TESS shifts its gaze from stars in the southern hemisphere to the northern, even more ground-based radial velocity facilities will be available to help TESS accomplish its goal of not just finding planets, but measuring their masses as well. The data will only come faster, and with it, presumably, an even richer and more numerous planet haul. “We’re off to the races now,” says Teske.