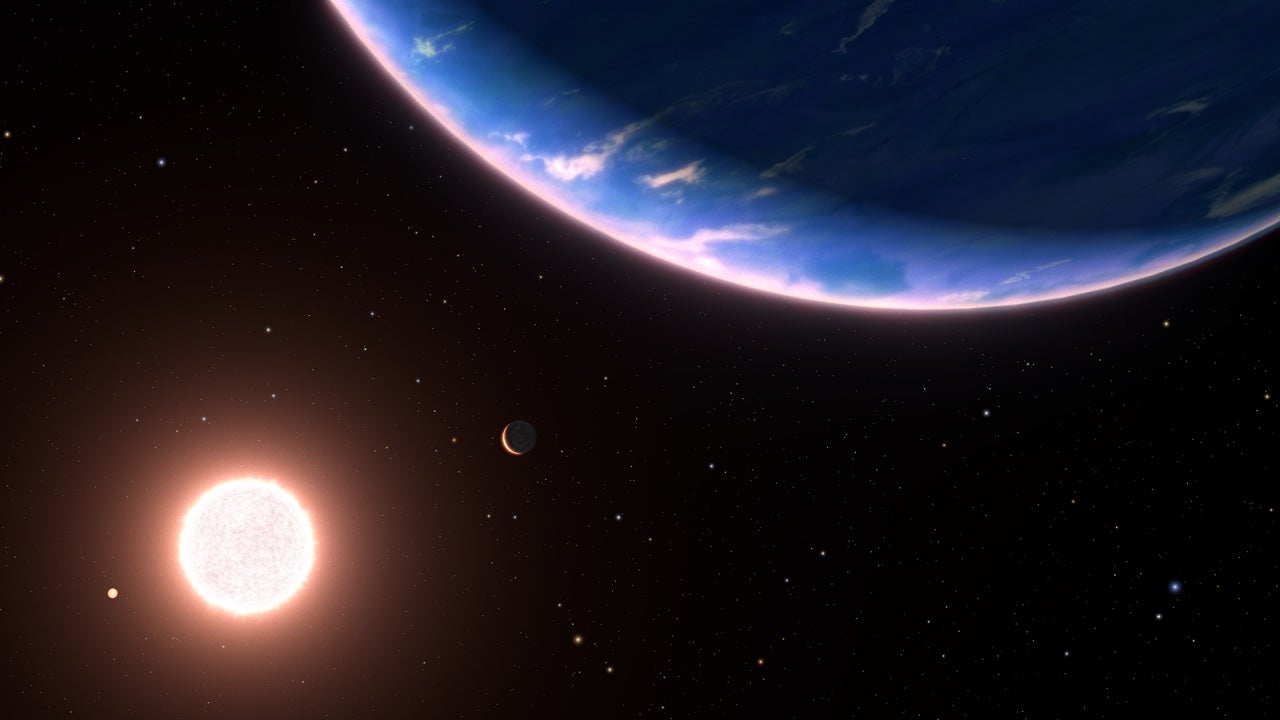

The Hubble Space Telescope captured a sign of water vapor in the atmosphere of a distant exoplanet, according to an analysis of observations published last year in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. Exoplanet GJ 9827 d is about two times Earth’s diameter. It is also the smallest exoplanet observed by Hubble with evidence of a potential water-rich atmosphere.

“This is an important step toward determining the prevalence and diversity of atmospheres on rocky planets,” said Björn Benneke, an astrophysicist at the Université de Montréal and study co-author in a NASA press release from earlier this year.

According to the paper, it is too early to tell what kind of atmosphere the planet has, but the authors present two scenarios. In the first, the water vapor that Hubble detected makes up just a small part of an atmosphere rich in hydrogen and helium, which would make for an unfamiliar planet that has no clear rocky analog in our own solar system. Alternatively, the atmosphere could be mostly water vapor, left behind after the hydrogen and helium have evaporated away, making it a candidate for what astronomers call a “water world.”

Either way, exoplanet GJ 9827 d would not exactly be earthlike — its surface temperature is about 800 degrees Fahrenheit (427 degrees Celsius), or as scorching as Venus. If it is a water world, it’s a steamy saunalike one, not a tropical paradise.

Still, “Water on a planet this small is a landmark discovery,” said co-principal investigator Laura Kreidberg of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy.

The exoplanet was first found in 2017 with NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope. Its star is 97 light-years away in the constellation Pisces.

The Hubble program observed the exoplanet over three years and 11 transit events where the exoplanet moved in front of its star. The exoplanet completes an orbit every 6.2 days.

“This Hubble discovery opens the door to future study of these types of planets by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope,” said Thomas Greene, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Ames Research Center. “JWST can see much more with additional infrared observations, including carbon-bearing molecules like carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and methane. Once we get a total inventory of a planet’s elements, we can compare those to the star it orbits and understand how it was formed.”