Astronomers say they have never seen such a bright, variable, high-energy, long-lasting burst. Usually, gamma-ray bursts mark the destruction of a massive star, and flaring emission from these events never lasts more than a few hours.

Although research is ongoing, astronomers feel the unusual blast likely arose when a star wandered too close to its galaxy’s central black hole. Intense tidal forces probably tore the star apart, and the infalling gas continues to stream toward the hole. According to this model, the spinning black hole formed an outflowing jet along its rotational axis. A powerful blast of X-rays and gamma rays is seen when the jet is pointed in our direction.

On March 28, Swift’s Burst Alert Telescope discovered the source in the constellation Draco when it erupted with the first in a series of powerful blasts.

“We know of objects in our own galaxy that can produce repeated bursts, but they are thousands to millions of times less powerful than the bursts we are seeing. This is truly extraordinary,” said Andrew Fruchter from the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland.

Swift determined a position for the explosion, which now is cataloged as gamma-ray burst (GRB) 110328A, and informed astronomers worldwide.

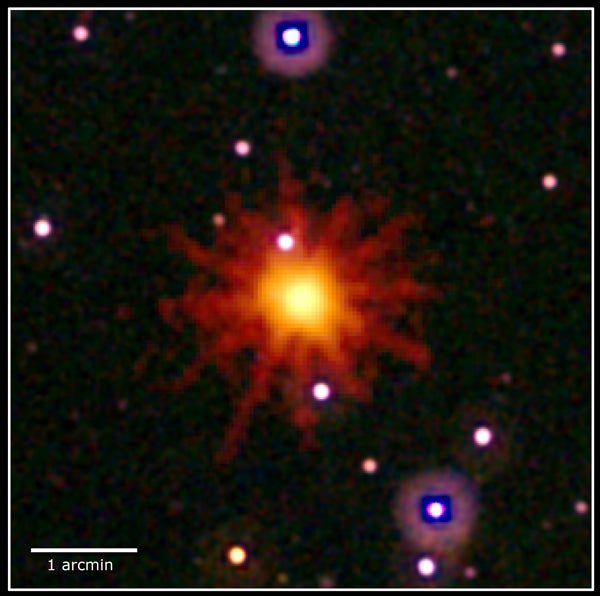

As dozens of telescopes turned to study the spot, astronomers quickly noticed a small, distant galaxy near the Swift position. A deep image taken by Hubble April 4 pinpointed the source of the explosion at the center of this galaxy, which lies 3.8 billion light-years away from Earth. That same day, astronomers used NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory to make a 4-hour exposure of the puzzling source. The image, which locates the X-ray object 10 times more precisely than Swift, shows it lies at the center of the galaxy Hubble imaged.

“We have been eagerly awaiting the Hubble observation,” said Neil Gehrels from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “The fact that the explosion occurred in the center of a galaxy tells us it is most likely associated with a massive black hole. This solves a key question about the mysterious event.”

Most galaxies, including our own, contain central black holes with millions of times the Sun’s mass; those in the largest galaxies can be a thousand times larger. The disrupted star probably succumbed to a black hole less massive than the Milky Way’s, which has a mass 4 million times that of our Sun.

Astronomers previously have detected stars disrupted by supermassive black holes, but none has shown the X-ray brightness and variability seen in GRB 110328A. The source has undergone numerous flares. Since April 3, for example, it has brightened by more than 5 times.

Scientists think the X-rays may be coming from matter moving near the speed of light in a particle jet that forms along the rotation axis of the spinning black hole as the star’s gas falls into a disk around the black hole.

“The best explanation at the moment is we happen to be looking down the barrel of this jet,” said Andrew Levan from the University of Warwick in the United Kingdom. “When we look straight down these jets, a brightness boost lets us view details we might otherwise miss.”

This brightness increase, which is called relativistic beaming, occurs when matter moving close to the speed of light is viewed nearly head on. Astronomers plan additional Hubble observations to see if the galaxy’s core changes brightness.

Astronomers say they have never seen such a bright, variable, high-energy, long-lasting burst. Usually, gamma-ray bursts mark the destruction of a massive star, and flaring emission from these events never lasts more than a few hours.

Although research is ongoing, astronomers feel the unusual blast likely arose when a star wandered too close to its galaxy’s central black hole. Intense tidal forces probably tore the star apart, and the infalling gas continues to stream toward the hole. According to this model, the spinning black hole formed an outflowing jet along its rotational axis. A powerful blast of X-rays and gamma rays is seen when the jet is pointed in our direction.

On March 28, Swift’s Burst Alert Telescope discovered the source in the constellation Draco when it erupted with the first in a series of powerful blasts.

“We know of objects in our own galaxy that can produce repeated bursts, but they are thousands to millions of times less powerful than the bursts we are seeing. This is truly extraordinary,” said Andrew Fruchter from the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland.

Swift determined a position for the explosion, which now is cataloged as gamma-ray burst (GRB) 110328A, and informed astronomers worldwide.

As dozens of telescopes turned to study the spot, astronomers quickly noticed a small, distant galaxy near the Swift position. A deep image taken by Hubble April 4 pinpointed the source of the explosion at the center of this galaxy, which lies 3.8 billion light-years away from Earth. That same day, astronomers used NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory to make a 4-hour exposure of the puzzling source. The image, which locates the X-ray object 10 times more precisely than Swift, shows it lies at the center of the galaxy Hubble imaged.

“We have been eagerly awaiting the Hubble observation,” said Neil Gehrels from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “The fact that the explosion occurred in the center of a galaxy tells us it is most likely associated with a massive black hole. This solves a key question about the mysterious event.”

Most galaxies, including our own, contain central black holes with millions of times the Sun’s mass; those in the largest galaxies can be a thousand times larger. The disrupted star probably succumbed to a black hole less massive than the Milky Way’s, which has a mass 4 million times that of our Sun.

Astronomers previously have detected stars disrupted by supermassive black holes, but none has shown the X-ray brightness and variability seen in GRB 110328A. The source has undergone numerous flares. Since April 3, for example, it has brightened by more than 5 times.

Scientists think the X-rays may be coming from matter moving near the speed of light in a particle jet that forms along the rotation axis of the spinning black hole as the star’s gas falls into a disk around the black hole.

“The best explanation at the moment is we happen to be looking down the barrel of this jet,” said Andrew Levan from the University of Warwick in the United Kingdom. “When we look straight down these jets, a brightness boost lets us view details we might otherwise miss.”

This brightness increase, which is called relativistic beaming, occurs when matter moving close to the speed of light is viewed nearly head on. Astronomers plan additional Hubble observations to see if the galaxy’s core changes brightness.