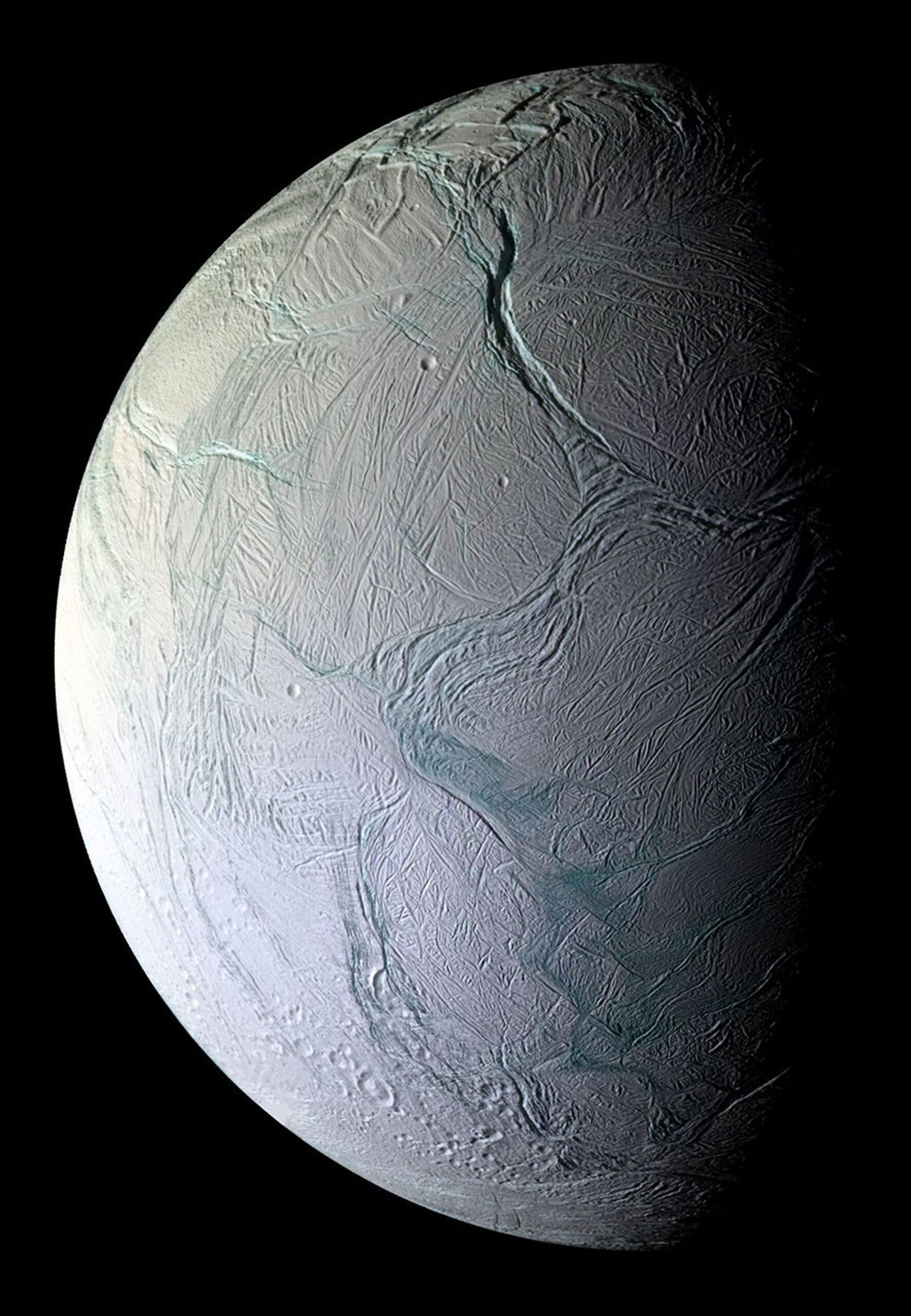

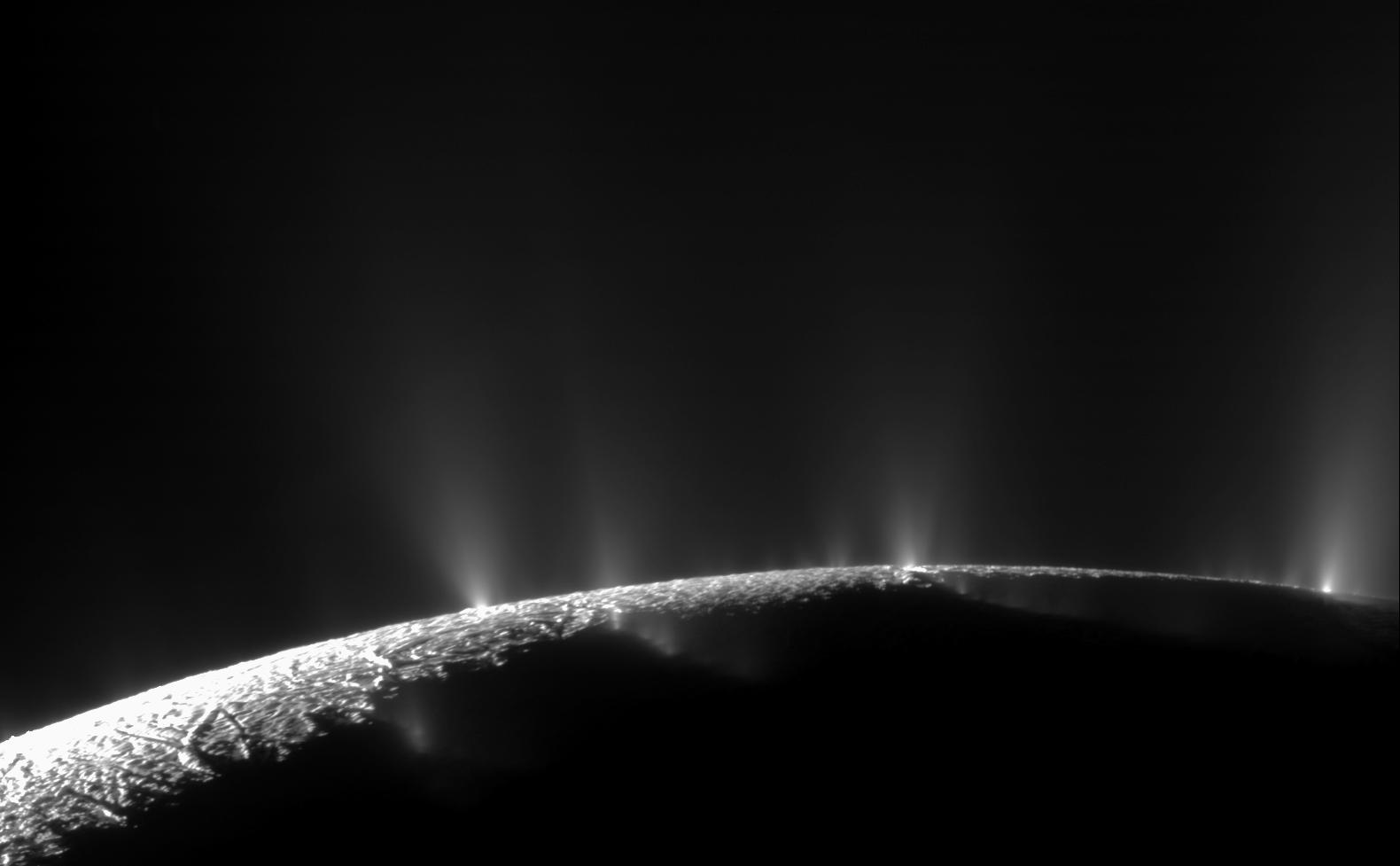

Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

Saturn’s exuberant moon, Enceladus, will receive a pair of visitors in the near future. The European Space Agency (ESA) is preparing a combined orbiter and lander to visit the icy satellite. Still in the planning stages, the mission is slated to study the saturnian system in the 2050s. The icy moon is considered one of the best potential habitats for life in the solar system.

“If you’re going to do a big mission, you want to do something new,” Jörn Helbert, an ESA study scientist for the pending mission, said in September at the annual combined Europlanet Science Congress-Division for Planetary Sciences conference in Helsinki, Finland. “We don’t want to repeat what others have done before.”

In 2021, ESA’s long-term scientific plan, Voyage 2050, put out a call for missions relating to “Moons of the Giant Planet.” In 2024, the Expert Committee for the Large-class mission identified Enceladus as a top target. The yet-unnamed L4 mission will explore Saturn’s moons before camping at Enceladus. A lander will set down on the moon, hunting its secrets, for a minimum of two weeks while the orbiter continues to circle in space.

“In order not to confuse people too much, we typically now refer to it as ‘L4 – the mission to Enceladus’,” Helbert saysby email. That follows ESA’s JUICE, NewAthena, and LISA flagship missions.

“The L4 mission will definitely happen, and it will very likely go to Enceladus,” Helbert says. Part of the timeline relies on a meeting by ESA’s governing body at the end of November, which will clarify the budget for the next few years.

Helbert says the mission is currently in a detailed study phase, having successfully completed two industrial studies to confirm its feasibility. Details will be presented at a workshop at the end of 2026, and then the call will go out for instruments. That should lead to mission adoption around 2034, at which point ESA is fully committed to the mission.

Currently, a working group of payload experts from across Europe is striving to determine what kind of instruments are best suited for the spacecraft. That, in turn, will help the team to refine the mission design in order to meet the instruments’ requirements.

“A diverse suite of instruments is essential for a comprehensive characterization of Enceladus’ habitability,” says Tara-Marie Bründl, a Payload Study Engineer and part of the ESA study team for the mission.

“Enceladus is the one place where we have direct access to a subsurface ocean through the active plume,” Helbert says. “The combination of having all elements for habitability and the possibility to look for biosignatures in samples from the subsurface ocean makes Enceladus such an interesting target.”

Cassini was a great first step

In 2004, NASA’s Cassini mission arrived in the saturnian system, beginning a string of flybys of the various moons. From the start, Cassini studied the myriad satellites in depth — currently the planet has 274 moons in confirmed orbits — revealing details that couldn’t be seen from Earth.

Today, many moons of the outer solar system are thought to have water hidden beneath their crust. Enceladus is the only one that we know of that is actively sharing that material with its neighbors. In 2005, scientists realized the moon was spurting material from its southern pole, from gaps known as the “tiger stripes.”

Researchers used Cassini’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer, an instrument designed to study dust particles in space, to examine one of the myriad plumes when the spacecraft flew through it. Although not specifically created to collect material jetting from a world, the CDA provided a hint about what’s happening beneath the surface of Enceladus.

“The Cassini-Huygens orbiter-probe mission already extensively studied the saturnian system, thereby providing valuable insights into its environmental conditions and its challenge for spacecrafts,” Bründl says. But “Cassini was not expecting such a geologically active moon as Enceladus.” Bründl says that the instruments lacked the resolution required to accurately detect complex organic molecules with certainty.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Returning to Saturn

L4 is tentatively planning for a 2042 launch, arriving in the early 2050s, when Saturn receives constant illumination from the Sun. While Enceladus is the primary focus of the mission, L4 will spend some time reconnoitering the neighborhood, examining moons like Titan, the only known world beyond Earth to boast liquid on its surface, and Mimas, suspected of hiding a relatively new ocean beneath its crust.

That will include a preliminary peek at Enceladus. It’s possible that the orbiter will sample the plumes as it tours the system, though that’s not yet been decided. Doing so would allow researchers more time to analyze the data before sending down the lander, Helbert says. Additional samples may be collected in the orbital phase before the lander is released.

”The main objective of the orbiter will be the global study of Enceladus and the other saturnian moons during the moon tour,” Helbert says. “At Enceladus, it will perform a detailed reconnaissance of the south pole area to identify safe landing areas.”

While the orbiter hovers overhead, the lander will touch down on the icy surface of the moon. The two will work in concert during the lander’s lifetime, tentatively set between two and four weeks. “Of course, we would like to operate the lander as long as possible,” Helbert says.

One of the biggest challenges with the lander is power. Rovers and landers on Mars can rely on solar energy to boost their lifetime. But Saturn is significantly farther from our star, and receives roughly 1 percent of the sunlight that reaches Earth. All power on the lander must come from its batteries. Helbert says that recent developments in high-energy density batteries will help power the lander.

An even bigger challenge is safely landing the instrument on a surface that is largely unknown and ensuring it survives long enough at low temperatures to achieve its scientific goals. Observations made from space should help the team identify a relatively safe landing spot. Additionally, the lander will utilize autonomous hazard avoidance to select a site within that area. Two independent, year-long studies determined the process to be technically feasible.

During its brief activity, the lander will study both the surface and, potentially, the subsurface. Helbert says that recently distributed material on the landscape could prove sufficient for sampling. However, the possibility remains that the engine itself could contaminate the site as it lands, something the team is working hard to avoid. But the potential alone may be enough reason to obtain a sample from beneath the surface.

But positioning the lander requires tradeoffs.

“We want to land close enough that we have significant infall of plume material,” Helbert says. At the same time, “we don’t want to risk ’falling into’ one of the tiger stripes.”

Bründl calls the lander “a pivotal element for delivering unprecedented scientific data from the surface compared to past missions that conducted Enceladus flybys,” a determination she said was made by a committee of science experts.

“Unlike prior missions that relied exclusively on sampling material from Enceladus’ plumes, the L4 lander will collect larger quantities of samples directly from the surface, enabling statistically higher-quality data,” she says.

Protect the world

While Enceladus is searching for hints of life, ESA will be working hard to ensure it doesn’t bring any with it from Earth. Helbert says that the L4 team is working closely with ESA planetary protection officer and the COSPAR planetary protection panel to minimize any risk of the transfer of material from our rock.

“It is critical to adopt a strict planetary protection policy to prevent potential contamination from Earth and avoid false positive detections of biomolecules,” Bründl says.

That will be a special challenge when the spacecraft drops to the surface.

“Avoiding contamination of the landing site is the key driver for the landing system design, from the placement to the braking engines to the actual design of the descent profile,” Helbert says.

He says that the lander will be sterilized before launch, then held inside of a bioshield until its arrival at the moon, ensuring that it isn’t contaminated during the launch or journey.

“This is also important from the scientific perspective as we want to ensure that any biosignatures we detect are actually from Enceladus and not brought along from Earth,” he says.

The orbiter will be disposed of in a graveyard orbit that will keep it from crashing into Enceladus for at least a thousand years, a time frame based on planetary protection protocols. That orbit won’t allow it to function as a communication relay for the lander, making it a hard stop for collecting material from the surface.

“This is an incredibly exciting mission and I feel very fortunate to be involved with development,” Helbert says. “I can’t wait to see the view from the surface of Enceladus.”