Titan’s northern hemisphere is set for fine spring weather, with polar skies clearing since the equinox in August of last year. Cassini’s Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) instrument has been monitoring clouds on Titan continuously since the spacecraft went into orbit around Saturn. Now, a team led by Sebastien Rodriguez from the AIM laboratory at the Universite Paris Diderot has used more than 2,000 VIMS images to create the first long-term study of Titan’s weather that includes the equinox using observational data.

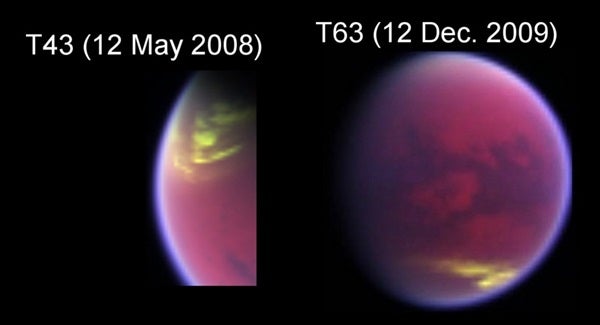

Together with Saturn in its 30-year orbit around the Sun, Titan has seasons that last for 7 terrestrial years. The team observed significant atmospheric changes between July 2004, early summer in the southern hemisphere, and April 2010, the very start of northern spring. The images show that cloud activity has recently decreased near both of Titan’s poles. These regions had been heavily overcast during the late southern summer until 2008, a few months before the equinox.

“Over the past 6 years, we’ve found that clouds appear clustered in three distinct latitude regions of Titan — large clouds at the north pole, patchy cloud at the south pole, and a narrow belt around 40° south,” said Rodriguez. “However, we are now seeing evidence of a seasonal circulation turnover on Titan — the clouds at the south pole completely disappeared just before the equinox, and the clouds in the north are thinning out. This agrees with predictions from models, and we are expecting to see cloud activity reverse from one hemisphere to another in the coming decade as southern winter approaches.”

The team has used results from the Global Climate Models (GCMs) developed by Pascal Rannou from the Institut Pierre Simon Laplace in France to interpret the evolution of the observed cloud patterns over time. By a constant influx of ethane and aerosols from the stratosphere, northern polar clouds of ethane form in Titan’s troposphere during the winter at altitudes of 19-31 miles (30-50 kilometers). In the other hemisphere, the upwelling from the surface of air enriched in methane produces mid- and high-latitude clouds. Observations of the location and activity of Titan’s clouds over long periods are vital in developing a global understanding of Titan’s climate and meteorological cycle.

Since Cassini reached Saturn, VIMS has acquired more than 20,000 images of Titan. The VIMS instrument consists of two detectors, one that maps in visible wavelengths and the other that maps in infrared, which also gather spectral information about the composition of observed targets. Rodriguez and his colleagues filtered the images to eliminate nighttime and distorted views, ending up with around 2,000 that were useful for identifying cloud activity. However, with the need to analyze each pixel in each image to identify the spectral properties of clouds, this was too vast a dataset for the team to evaluate manually.

“Even having eliminated 90 percent of the images, we were still left with several million spectra to analyze,” said Rodriguez. We developed a computer program that picked out the cloudy pixels, and we then went back and visually checked the detections to make sure that they were relevant.”

In February 2010, the Cassini mission was extended to a few months past Saturn’s northern summer solstice in May 2017. This means that Rodriguez and his team will be able to observe seasonal changes from mid-winter to mid-summer in the northern hemisphere.

“We have learned a lot about Titan’s climate since Cassini arrived at Saturn, but there is still a great deal to learn,” said Rodriguez. “With the new mission extension, we will have the opportunity to answer some of the key questions about the meteorology of this fascinating moon.”