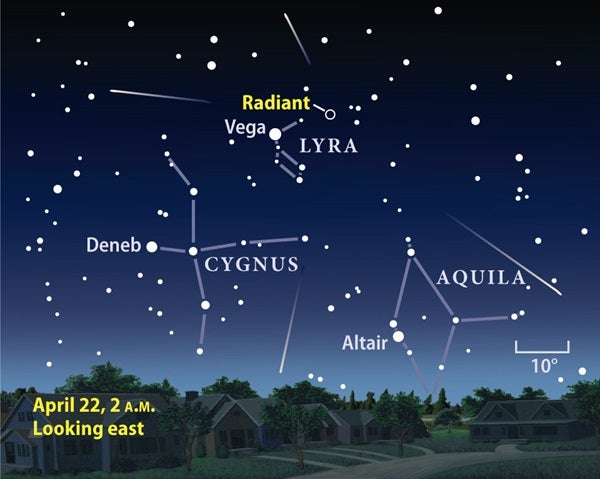

The annual Lyrid meteor shower is typically one of the best of the year. In 2009, this shower occurs at a time when the Moon is nearly New, so its light won’t wash out any meteors. The Lyrid meteor shower has bright, fast meteors, and many of them leave smoke trails visible for several seconds.

The Lyrids’ peak (that is, the best time to see the meteors), occurs in the predawn hours of April 22.

If the 22nd is cloudy, don’t worry. That’s not the only date you can observe Lyrids. This year, the shower will be active between about April 16 and the 25th. Of course, you’ll see fewer meteors the farther you observe from the peak.

You’ll need a clear, dark sky to see more than just a few Lyrids. “Dark” means that you’re at least 40 miles from the lights of a large city. Don’t view through a telescope or binoculars. Your eyes alone work best because they provide the largest field of view. That said, if you have binoculars you can use them to follow any persistent smoke trails left by the meteors.

Around midnight on Wednesday morning, April 22, set up a lawn chair, preferably one that reclines. The Moon will rise just before sunrise, so it won’t pose a problem. Adjust your chair so you’re looking generally overhead. Glancing around won’t hurt anything.

In addition to your chair, bring a blanket, cookies, fruit, and your favorite beverage — no booze, though. Alcohol interferes with the eye’s dark adaption as well as the visual perception of events.

How many Lyrids will you see? If your sky is clear, you can expect to count about 20 meteors an hour from a dark site. But the rate varies. In 1982, observers counted 90 meteors an hour.

The Lyrids were given that name because if you trace all the meteor trails backward, they would meet in the constellation Lyra the Lyre.

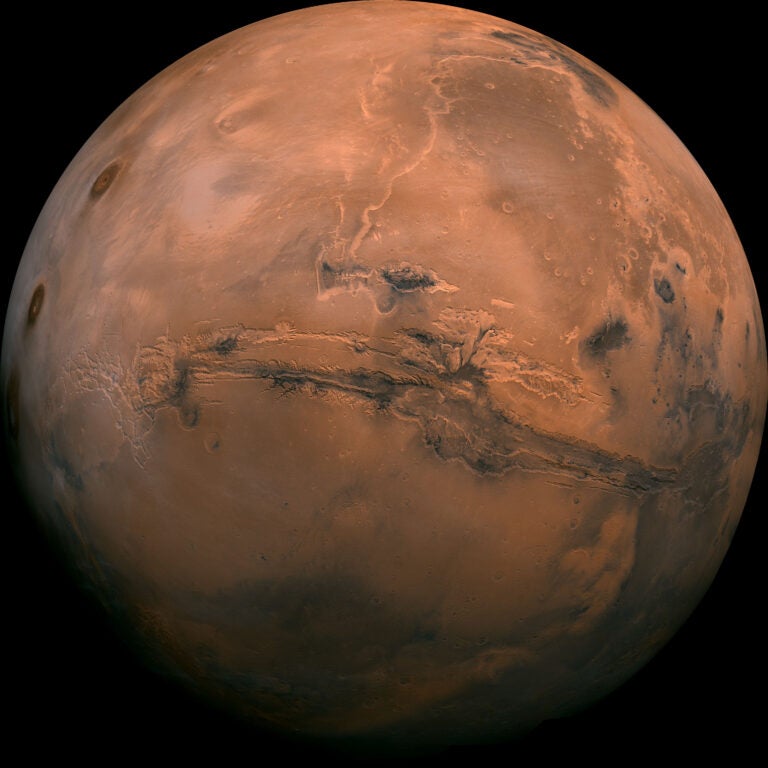

This meteor shower comes from particles released by Comet C/1861 G1 (Thatcher), or just Comet Thatcher. Amateur astronomer A. E. Thatcher discovered this comet April 5, 1861. Because it takes 415 years to orbit the Sun, Comet Thatcher won’t return until the year 2276.

The Lyrids ranks as the oldest meteor shower on record. The Chinese observed it in 687 B.C.

Lyrid meteors are fast — their speeds top 107,000 mph — and about 15 percent leave smoke trails that can last several seconds. Many Lyrids are also bright. The average magnitude for a Lyrid meteor is 2.4.

And while I’m at it, here are a few more tidbits about meteor showers:

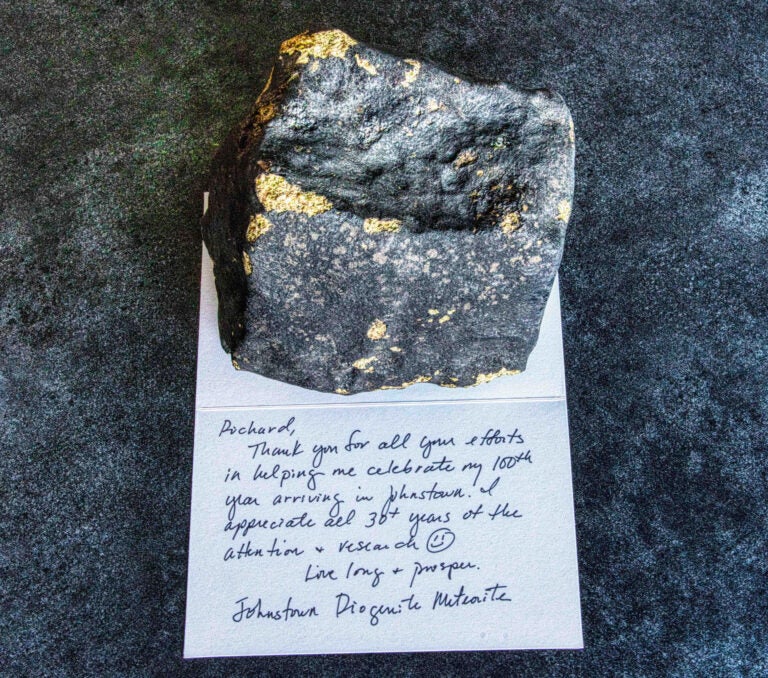

- Meteors are small particles of rock and metal Earth runs into as it orbits the Sun. When the particles are in space, astronomers call them meteoroids. When they burn up in the atmosphere, they become meteors. If they survive the passage through our thick blanket of air and land on Earth, we call them meteorites.

- Comets cause most meteor showers. When a comet swings around the Sun, it leaves a trail of debris (small meteoroids). Sometimes, the orbit of this debris crosses Earth’s orbit. When Earth runs into this stream of particles, we experience a meteor shower.

- The typical bright meteor comes from a particle no larger than a pea weighing less than 1 gram.

- The average hourly rate for random meteors on a “non-shower” night is 6 per hour.

- Sky-event preview: Watch the Lyrid meteor shower

- Interactive star chart — StarDome will give you an accurate map of your sky. This tool will help you locate the meteor shower’s radiant in the constellation Lyra.

- Video: How to observe meteor showers — Enjoying a meteor shower requires only comfort and patience. Senior Editor Michael E. Bakich gives tips on spending a night under “shooting stars.”

- Meteors and meteor showers — You can see a “shooting star” on any dark night, but some nights of the year are much better than others.

- Free weekly e-mail newsletter — Receive news, sky-event information, observing tips, and more.