Key Takeaways:

“I think the solar system saved the best for last,” Principal Investigator Alan Stern said in a press conference at NASA Headquarters.

New Horizons co-investigator Jeff Moore said the newly unveiled vast craterless plain that can’t be easily explained, but surely has a strange story to tell.

“I’m still having to remind myself to take deep breaths,” he said. “The landscape geology is just astoundingly amazing.”

While larger-scale images of Pluto show ancient craters that are perhaps billions of years old, Tombaugh Regio is very young with signs of ongoing erosion and fractures that imply some form of tectonics.

“Pluto is every bit as geologically active as any place we’ve seen in the solar system,” Moore said.

The landscape bares a strong resemblance to Mars’ arctic regions, as it’s webbed with a similar network of potentially wind-swept or even erupted features, plus polygons and cracks — some of which are filled with a dark material that has the team excited.

“Judging form the absence of impact craters, it’s clear Sputnik Planum couldn’t be older than 100 million years old and perhaps much younger even,” Moore said, adding that “it could be a week old for all we know.”

Finding cryovolcanism — ice volcanoes — would be among the most exciting finds from Pluto. However, the New Horizons team was careful to say it hadn’t yet found plumes like those of Neptune’s moon Triton and other icy bodies. However, the images are still just a few of the stream that will continue to flood out over more than the next year, giving even better resolution on Pluto’s surprising complexity.

“I’m an old-fashioned geologist,” Moore added. “I want to see unambiguous evidence that something is erupting up into the atmosphere.”

It’s possible that Pluto could contain a large accumulation of radioactive elements that provide heat, but it’s not clear how these elements could have kept from decaying over the course of solar system history. Another option is that Pluto might have a subsurface ocean, but astronomers have typically thought of such ocean worlds as being heated by the tidal tugs of large planets like Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune, and Uranus.

Other astronomers not on the mission have voiced skepticism that Pluto is as geologically active as it seems on the surface, suggesting that ice might deposit on top of old features, making them look new.

“Across the rest of this disk, there is nothing like this carbon monoxide,” said Stern, who is also principal investigator for the Ralph instrument.

First peek at Pluto’s atmosphere

Alice — the spacecraft’s atmosphere investigating instrument — and SWAP (Solar Wind Around Pluto) also had tantalizing bits in their early data. Based on laboratory ice studies and ground-based observations, astronomers had some basic ideas about Pluto’s surface and atmosphere. On top of the dwarf planet’s water ice interior is a veneer of some 90 percent nitrogen and 10 percent methane, with other more complex hydrocarbons mixed in.

Alice has already shown that Pluto’s upper atmosphere is nitrogen, with methane lower down. And closer to the surface, those heavier hydrocarbons can be detected absorbing the weak sunlight.

Randy Gladstone, another New Horizons co-investigator, said that more atmospheric results should come in the next several months, but the team is already doing science with the data it has.

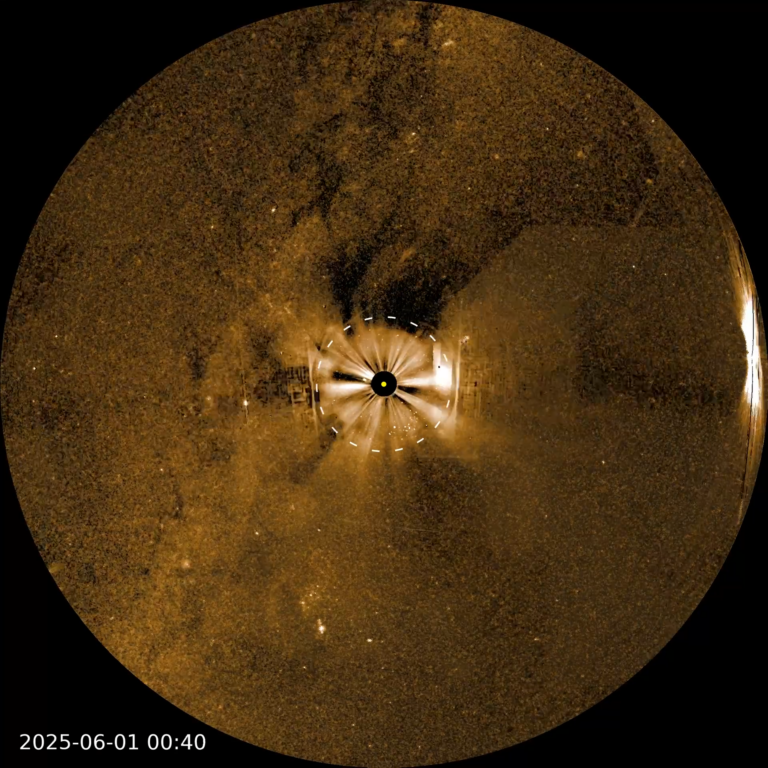

Meanwhile, SWAP found that Pluto’s nitrogen is escaping and interacting with the solar wind in a major way.

“We see behind Pluto an ion tail that’s being carried away in the solar wind,” said Fran Bagenal, New Horizons co-investigator. “When we get the rest of the data back in August, we really will be able to quantify the amount of that escaping atmosphere.”

Bagenal said their early measurements indicate that Pluto is losing about 500 tons of nitrogen into space every hour — a rate 500 times larger than what NASA’s MAVEN spacecraft has seen at Mars.

She added that if you add up the loss over the age of the solar system, Pluto has lost about 9,000 feet (275 meters) of ice, which is the equivalent of a large mountain.

Stern said he expected to have more “big news” at a press conference scheduled for next Friday, July 24.