Perseus lies in the northeastern sky. In mythology, his bravery saved Princess Andromeda from certain death. Cepheus — Andromeda’s father — stands high in the northern sky. The autumn Milky Way’s faint stream immerses both constellations, which hold many binocular treats.

While these two figures boast impressive resumés, let’s turn our attention toward an often-ignored Mr. October: Aquarius the Water-bearer. Greek mythology identifies Aquarius as Ganymede, Zeus’ favorite water boy. According to legend, Zeus deified Ganymede as Aquarius, the god of rain. He was eventually raised into the sky as one of the 12 zodiacal constellations.

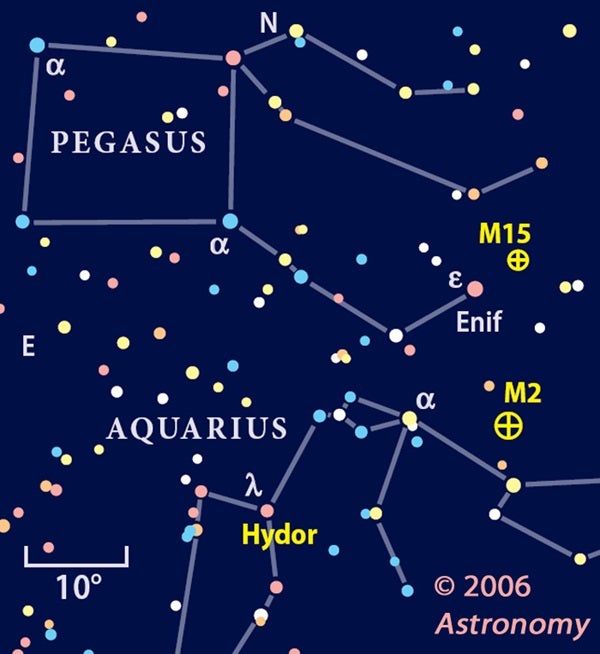

Light pollution often masks the constellation’s faint outline. To begin your binocular tour of Aquarius, start at the Great Square of Pegasus. Draw an imaginary line diagonally from the Square’s northeastern star, Alpheratz (Alpha [α] Andromedae), to Markab (Alpha Pegasi), at the southwest corner. Continue the line an equal distance farther southwest. There, you should find a Y-shape asterism made up of 4th- and 5th-magnitude stars known as Aquarius’ water jar. All of the stars fit into most binocular fields of view. Add in the star Sadalmelik (Alpha Aquarii) to their west, and you can form a convincing arrowhead.

I enjoy comparing similar types of objects, and we have a great opportunity to do just that with M2. If you head about 2 binocular fields north, you’ll zero in on another globular cluster, M15 (NGC 7078), in Pegasus. M15 lies about 4°, or ½ a binocular field, northwest of the star Enif at the tip of Pegasus’ nose. Look for a 6th-magnitude star just to the cluster’s west. Together, they create an unusual “double star.” It’s easy to tell the globular from the star, because M15 will look noticeably fuzzy. Compare the two globulars. M15 will probably strike you as slightly smaller than M2, and maybe even brighter.

M15 was the first globular cluster found to contain a planetary nebula. In 1921, German astronomer Friedrich Kuster spotted the planetary, but he thought it was just a cluster star. The nebula’s identity wasn’t deduced until 1927, when Francis Pease studied M15 with the 100-inch Hooker reflector at Mount Wilson. We now know this nebula as Pease 1. Although Pease 1 can be spotted through the largest amateur telescopes, it’s a tough challenge.

Finally, head back to the water jar, and then move about 10° southeast to the star Hydor (Lambda [λ] Aquarii). A glance through binoculars shows Hydor radiating a red or orange glow. As a red giant star, Hydor measures about 100 times the diameter of our Sun.

Hydor almost lies on the ecliptic, so the Sun, Moon, and most planets will occasionally pass its way. As October opens, Uranus lies less than 1° southeast of Hydor. The 6th-magnitude planet’s tiny green disk contrasts nicely with the red hue of the 4th-magnitude star, and the two create a colorful pairing through binoculars. As the month progresses, watch Uranus move to the star’s west and complete a retrograde loop in the sky. If you have never seen Uranus, this is a great opportunity to do so.

Incidentally, Neptune lies to the west of Uranus, in Capricornus. Drop by this month’s “online extra” for tips on finding the eighth planet through your binoculars.

Come back next month, and dress your best. We have an audience with the Queen. Till then, remember, when it comes to stargazing, two eyes are better than one!