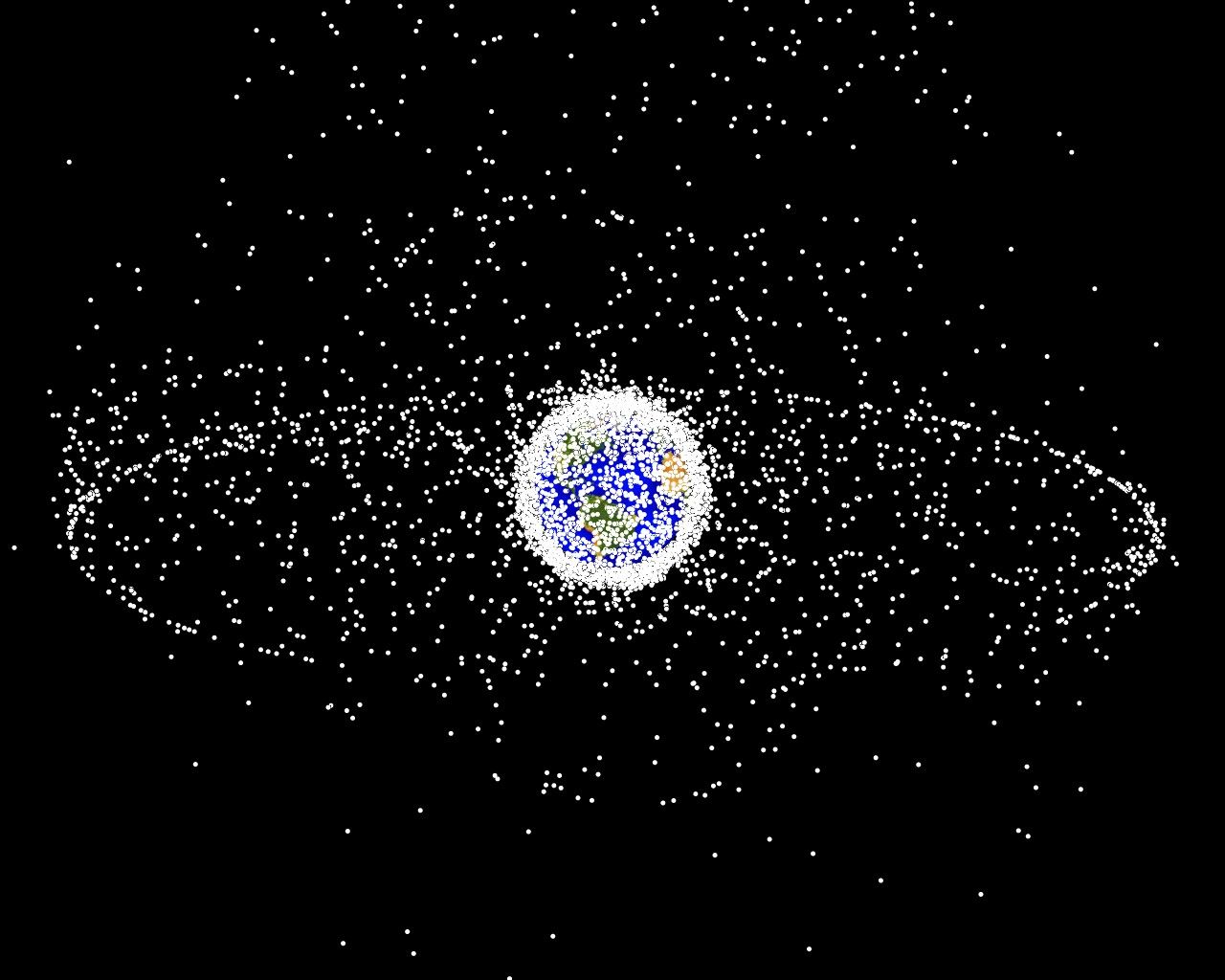

Credit: NASA Orbital Debris Program Office

Seismometers — equipment designed to pinpoint earthquakes — are now being used to track the thousands of pieces of human-made objects abandoned in Earth’s orbit. Some of those items pose a risk to humans when they fall to the ground. To locate possible crash sites, Benjamin Fernando, a postdoctoral research fellow at Johns Hopkins University, has helped to devise a way to track falling debris using existing networks of earthquake-detecting seismometers. Fernando doesn’t just study earthquakes, he also studies similar events on Mars and other planets in the solar system.

The new tracking method, published in the journal Science, generates data in near real-time. That information will help authorities to quickly locate and retrieve the charred remains, some of which could be toxic.

“Re-entries are happening more frequently. Last year, we had multiple satellites entering our atmosphere each day, and we don’t have independent verification of where they entered, whether they broke up into pieces, if they burned up in the atmosphere, or if they made it to the ground,” said lead author Fernando. “This is a growing problem, and it’s going to keep getting worse.”

Successful tracking

Fernando and colleague Constantinos Charalambous, a research fellow at Imperial College London, used seismometer data to reconstruct the path of debris from China’s Shenzhou-15 spacecraft after the orbital module entered Earth’s atmosphere April 2. The module measured some 3.5 feet (1.07 meters) wide and weighed more than 1.5 tons. The researchers targeted it because it could have posed a threat to people on the ground.

Space junk entering Earth’s atmosphere moves faster than the speed of sound. Because of its speed, each piece produces a sonic boom (shock wave) similar to those produced by a supersonic jet. As the debris streaks toward Earth, the shockwave trails behind, and its trail rumbles the ground and pings seismometers in its path. By collecting data from the activated seismometers, researchers can follow the debris’ trajectory, determine which direction it’s moving, and estimate where it may have landed.

By analyzing data from 127 seismometers in southern California, the researchers calculated the path and speed of Shenzhou-15. Traveling between 25 and 30 times the speed of sound, the module streaked through the atmosphere traveling northeast over Santa Barbara and Las Vegas.

The researchers used the intensity of the seismic readings to calculate the module’s altitude and pinpoint how it broke into fragments. Then, they used trajectory, speed, and altitude calculations to estimate correctly that the module was traveling approximately 25 miles (40 kilometers) north of the trajectory predicted by U.S. Space Command.

Important tracking

Because a lot of falling debris is burning, it sometimes produces toxic particulates that can linger in the atmosphere for hours and be carried by the wind to diverse locations. Knowing the trajectory of the debris will help organizations track those particulates, as well as who might be at risk of exposure, the researchers said. Such rapid tracking will also help authorities quickly retrieve objects that make it to the ground, the researchers said.

“In 1996, debris from the Russian Mars 96 spacecraft fell out of orbit. People thought it burned up, and its radioactive power source landed intact in the ocean. People tried to track it at the time, but its location was never confirmed,” Fernando said. “More recently, a group of scientists found plutonium in a glacier in Chile that they believe is evidence the power source burst open during the descent and contaminated the area. We’d benefit from having additional tracking tools, especially for those rare occasions when debris has radioactive material.”

Previously, scientists relied on radar data to follow an object decaying in low-Earth orbit and predict where it would enter the atmosphere. But re-entry predictions can be off by thousands of miles in the worst cases. Now, seismic data can complement radar data by tracking an object after it enters the atmosphere, providing the actual trajectory.

“If you want to help, it matters whether you figure out where it has fallen quickly — in 100 seconds rather than 100 days, for example,” Fernando said. “It’s important that we develop as many methodologies for tracking and characterizing space debris as possible.”