The observations help confirm the first objects were numerous in quantity and furiously burned cosmic fuel.

“These objects would have been tremendously bright,” said Alexander “Sasha” Kashlinsky from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “We can’t yet directly rule out mysterious sources for this light that could be coming from our nearby universe, but it is now becoming increasingly likely that we are catching a glimpse of an ancient epoch. Spitzer is laying down a roadmap for NASA’s upcoming James Webb Telescope, which will tell us exactly what and where these first objects were.”

Spitzer first caught hints of this remote pattern of light, known as the cosmic infrared background, in 2005, and again with more precision in 2007. Now, Spitzer is in the extended phase of its mission, during which it performs more in-depth studies on specific patches of the sky. Kashlinsky and his colleagues used Spitzer to look at two patches of sky for more than 400 hours each.

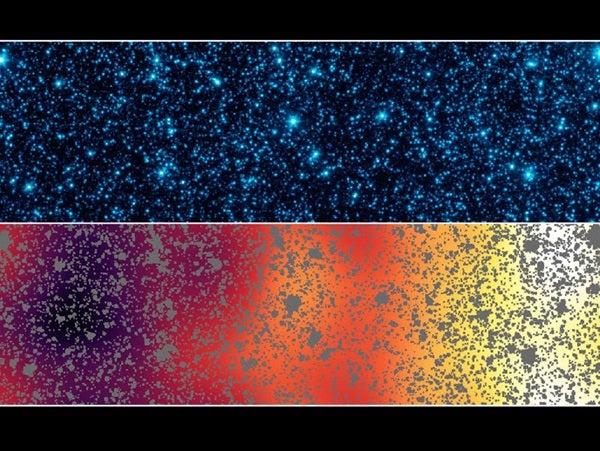

The team then carefully subtracted all the known stars and galaxies in the images. Rather than being left with a black, empty patch of sky, they found faint patterns of light with several telltale characteristics of the cosmic infrared background. The lumps in the pattern observed are consistent with the way the distant objects are thought to be clustered together.

Kashlinsky likens the observations to looking for Fourth of July fireworks in New York City from Los Angeles. First, you would have to remove all the foreground lights between the two cities, as well as the blazing lights of New York City itself. You ultimately would be left with a fuzzy map of how the fireworks are distributed, but they would still be too distant to make out individually.

“We can gather clues from the light of the universe’s first fireworks,” said Kashlinsky. “This is teaching us that the sources, or the ‘sparks,’ are intensely burning their nuclear fuel.”

The universe formed roughly 13.7 billion years ago in a fiery, explosive Big Bang. With time, it cooled, and by around 500 million years later, the first stars, galaxies, and black holes began to take shape. Astronomers say some of that “first light” might have traveled billions of years to reach the Spitzer Space Telescope. The light would have originated at visible or even ultraviolet wavelengths and then, because of the expansion of the universe, stretched out to the longer infrared wavelengths observed by Spitzer.

The new study improves on previous observations by measuring this cosmic infrared background out to scales equivalent to two Full Moons — significantly larger than what was detected before. Imagine trying to find a pattern in the noise in an old-fashioned television set by looking at just a small piece of the screen. It would be hard to know for certain if a suspected pattern was real. By observing a larger section of the screen, you would be able to resolve both small- and large-scale patterns, further confirming your initial suspicion.

Likewise, astronomers using Spitzer have increased the amount of sky examined to obtain more definitive evidence of the cosmic infrared background. The researchers plan to explore more patches of sky in the future to gather more clues hidden in the light of this ancient era.

“This is one of the reasons we are building the James Webb Space Telescope,” said Glenn Wahlgren from NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. “Spitzer is giving us tantalizing clues, but James Webb will tell us what really lies at the era where stars first ignited.”