The Moon’s surface is more complex than previously thought and was bombarded by two distinct populations of asteroids or comets in its youth, according to three new papers in the September 17 issue of Science that describe data from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO).

Two of the papers describe data from LRO’s Diviner Lunar Radiometer Experiment instrument that reveal the complex geologic processes that forged the lunar surface. The data showed previously unseen compositional differences in the crustal highlands and confirmed the presence of anomalously silica-rich material in five distinct regions.

All minerals and rocks absorb and emit energy with unique signatures that reveal their identity and formation mechanisms. For the first time, the Diviner instrument is providing scientists with global high-resolution infrared maps of the Moon, enabling them to make a definitive identification of silicate minerals commonly found within its crust. “Diviner is literally viewing the Moon in a whole new light,” said Benjamin Greenhagen of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, lead author of one of the Diviner papers.

Lunar geology can be roughly broken down into two categories — the anorthositic highlands, rich in calcium and aluminum, and the basaltic “maria,” giant impact basins filled with solidified lava flows that are abundant in iron and magnesium. Both of these crustal rocks are considered the direct result of crystallization from lunar mantle material, the partially molten layer beneath the crust.

Diviner’s observations have confirmed that most lunar terrains have signatures consistent with compositions in these two broad categories. But they have also revealed lunar soil compositions with more sodium than that of typical anorthosite crust. The widespread nature of these soils reveals that there may have been variations in the chemistry and cooling rate of the magma ocean that formed the early lunar crust, or they could be the result of secondary processing of the early lunar crust.

Most impressively, in several locations around the Moon, Diviner has detected highly silicic minerals such as quartz and potassium-rich and sodium-rich feldspar — minerals that are only associated with highly evolved lithologies, or rocks that have undergone extensive magmatic processing. Detection of silicic minerals at these locations is significant, as they occur in areas previously shown to exhibit anomalously high abundances of the element thorium, another proxy for highly evolved lithologies.

“The silicic features we’ve found on the Moon are fundamentally different from the more typical basaltic mare and anorthositic highlands,” said Timothy Glotch of Stony Brook University, New York, lead author of the second Diviner paper. “The fact that we see this composition in multiple geologic settings suggests that there may have been multiple processes producing these rocks.”

One thing not apparent in the data is evidence for pristine lunar mantle material, which previous studies have suggested may be exposed at some places on the lunar surface. Even in the South Pole Aitken basin, also known as SPA, the largest, oldest, and deepest impact crater on the Moon — deep enough to have penetrated through the crust and into the mantle — there is no evidence of mantle material.

The implications of this are as yet unknown. Perhaps there are no such exposures of mantle material, or maybe they occur in areas too small for Diviner to detect. But it’s likely that if the impact that formed this crater did excavate any mantle material, it has since been mixed with crustal material from later impacts inside and outside the basin.

“The new Diviner data will help in selecting the appropriate landing sites for potential future robotic missions to return samples from SPA,” Greenhagen said. “We want to use these samples to date the SPA-forming impact and potentially study the lunar mantle, so it’s important to use Diviner data to identify areas with minimal mixing.”

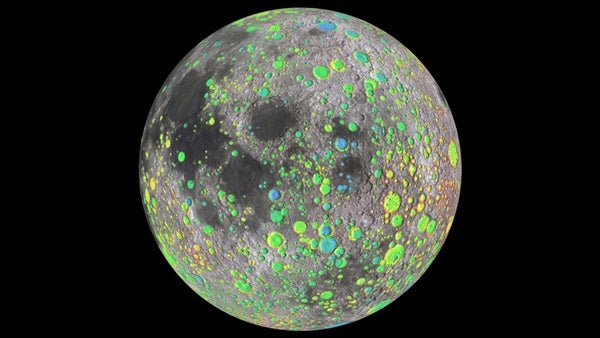

In the other paper, lead author James Head of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, describes an analysis of a detailed global topographic map of the Moon created using LRO’s Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter. This new dataset shows that the older highland impactor population can be clearly distinguished from the younger population in the lunar maria. The highlands have a greater density of large craters, implying that the earlier population of impactors had a proportionally greater number of large fragments than the population characterizing later lunar history, Head said.

Head said details about impactor populations on the Moon have implications for the earliest history of all the planets in the inner solar system, including Earth. “Like the Rosetta stone, the lunar record can be used to translate the ‘hieroglyphics’ of the poorly preserved impact record on Earth,” he said.

3-D computer simulations help scientists envision supernova explosions

NASA’s lunar spacecraft completes exploration mission phase

Chandra finds evidence for stellar cannibalism

The king of planets dominates the sky

Hubble data harvests distant solar system objects

Mercury at its morning best