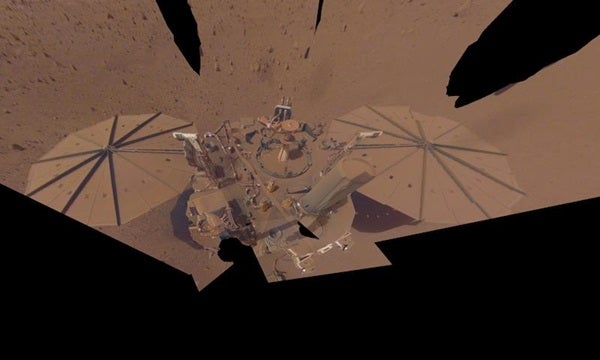

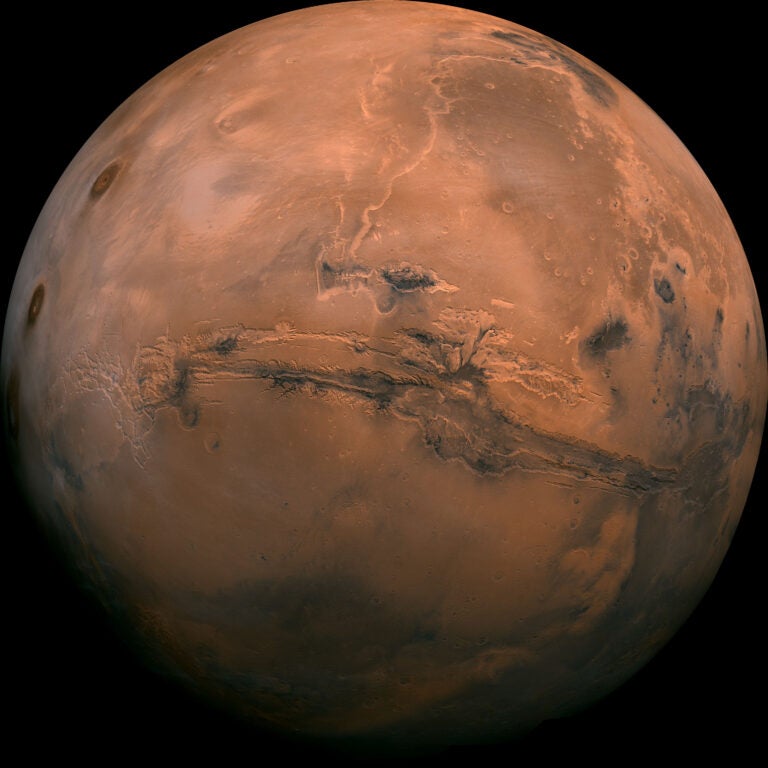

Cold, dusty Mars has claimed the life of yet another intrepid robotic explorer. On Dec. 21, NASA announced the end of the InSight mission to explore Mars’ interior. The decision came following two unsuccessful attempts to communicate with the lander, which had been running low on power as its solar panels sat beneath thickening blankets of rust-colored dust.

Long time coming

After landing on the Red Planet in November 2018, InSight’s initial mission was slated to last 708 sols (martian days), or nearly two Earth years. But that mission, which churned out reams of useful and unique data, was extended to run at least through the end of December 2022.

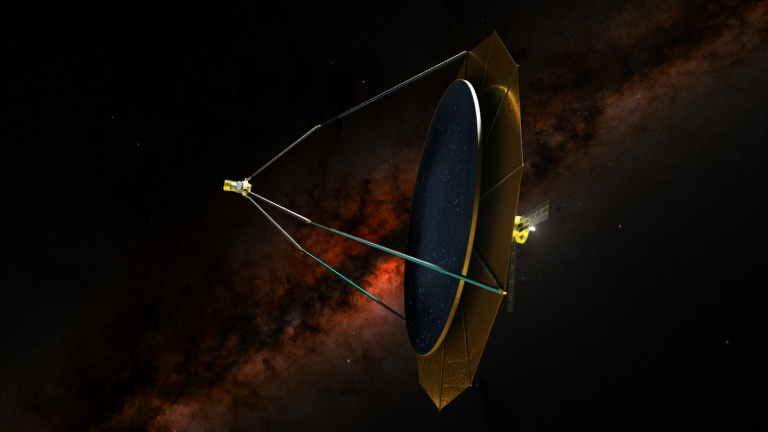

The stationary lander relied on power generated from its two large solar panels, which had been steadily gathering dust. That dust reduced the panels’ efficiency over time, forcing mission planners to make tough choices regarding power allotment.

In May, engineers placed the craft’s robotic arm into a final resting pose and turned off all its instruments, save one. InSight’s seismometer continued to operate on what little power was available, running about half the time, Bruce Banerdt, the mission’s principal investigator and principal research scientist, told Astronomy in late September.

At the time, Banerdt said: “We expect things to get worse sometime soon.” That’s because Mars had entered its dusty season, during which huge storms can fling sunlight-obscuring dust across the globe. And such conditions are exactly what brought about the eventual downfall of the long-lived Opportunity rover in 2018.

By early October, as a massive dust storm slashed the amount of available sunlight, InSight reported another drop in its power generation capacity. NASA shut down the mission’s seismometer to wait out the storm. And by November, NASA had turned back the seismometer back on to continue collecting data. But the end was nearing fast.

InSight last contacted Earth Dec. 15, after which two attempts — a benchmark previously set by NASA — were made to raise the lander. Both failed. And a few days later, NASA officially brought the mission to a close.

Many milestones

InSight, which is short for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy, and Heat Transport, was tasked with a simple yet challenging mission: unlock the mysteries of Mars’ interior. It did exactly that.

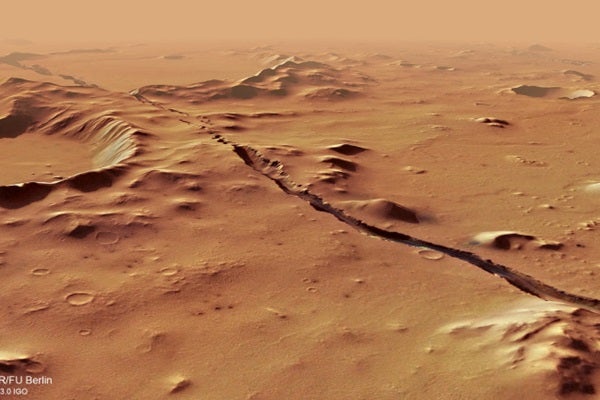

The mission’s top priorities included uncovering Mars’ internal structure by measuring the thickness of the crust, obtaining the size and density of the core, and sussing out the structure and composition of Mars’ mantle.

It accomplished all of that and more, says Banerdt, who adds that the details InSight uncovered are now “literally rewriting the textbooks on Mars. And I think that’s really the main legacy.”

The mission’s bountiful seismic data, which include more than 1,300 marsquakes — some of which were caused by meteorite impacts — will be added to an international archive. Those data can now provide “new insights into the structure and the activity of Mars for decades to come,” Banerdt says.

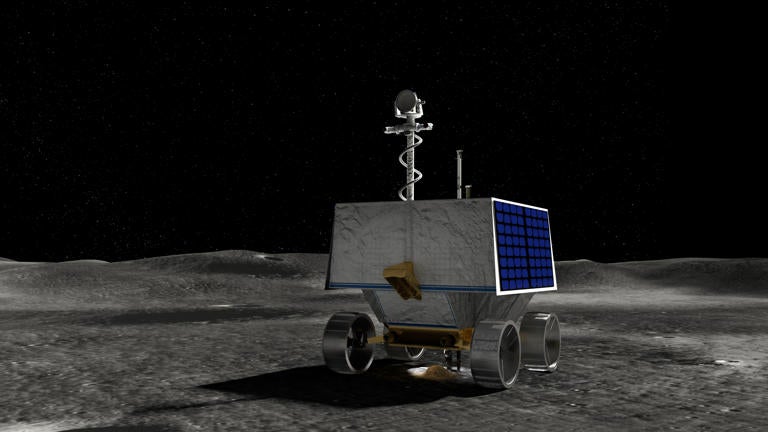

InSight’s meteorological instruments recorded about a year’s worth of weather data at the lander’s location with unprecedented accuracy, Banerdt adds. This will help pave the way for future planning of both robotic and crewed missions.

The InsSight lander also took the first magnetic field measurements on the surface of Mars and measured several properties of the soil around it — which can benefit future missions that might need to excavate, or even build, with readily available surface material.

Not everything was a rousing success, however. Most famously, the mission’s “mole” subsurface probe only penetrated about 16 inches (40 centimeters) deep, despite being designed to burrow to a depth of at least 3 feet (10 meters). It turned out that the soil beneath InSight’s struts was unlike any previously encountered on the surface; it simply didn’t cooperate with the instrument’s design. But even that cloud has a silver lining, as it provided scientists with important details about the terrain upon which InSight landed.

After years of monitoring the martian surface and subsurface around it, InSight is now forever quiet and still. But Banerdt notes that the lander’s success has reinvigorated the field of planetary seismology across the solar system. And it has also left Mars ripe for follow-up missions.

Although Banerdt admits the end of a mission is a sad moment, “I think that the plucky little lander has actually earned a rest,” he says. “It’s been working hard for us for a long time and I think it’s earned its retirement.”