European space scientists are getting closer to unraveling the origin of Mars’ moon, Phobos. Thanks to a series of close encounters by the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Mars Express spacecraft, the moon looks almost certain to be a rubble pile, rather than a single solid object. However, mysteries remain about where the rubble came from.

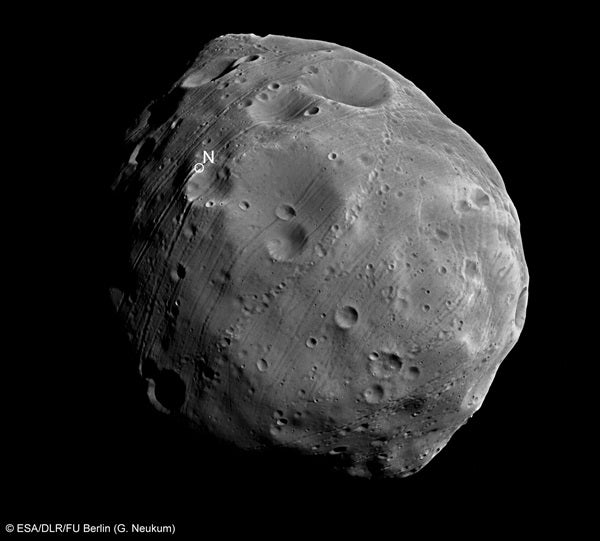

Unlike Earth, with its single large moon, Mars plays host to two small moons. The larger one is Phobos, an irregularly sized lump of space rock measuring just 17 miles by 14 miles by 12 miles (27 kilometers by 22 kilometers by 19 kilometers).

During the summer, Mars Express made a series of close passes to Phobos. It captured images at almost all flybys with the High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC). A team led by Gerhard Neukum from Freie Universitaet Berlin, including scientists from the German Aerospace Centre (DLR), is now using these and previously collected data to construct a more accurate 3-dimensional model of Phobos so its volume can be determined with more precision.

In addition, during one of the nearest flybys, the Mars Express Radio Science (MaRS) Experiment team led by Martin Paetzold from the University of Cologne, carefully monitored the spacecraft’s radio signals. They recorded the changes in frequency brought about by Phobos’ gravity pulling Mars Express. Tom Andert of the Universitaet der Bundeswehr Muenchen and Pascal Rosenblatt of the Royal Observatory of Belgium, both members of the MaRS team, are using the data to calculate the precise mass of the martian moon.

Putting the mass and volume data together, the teams will be able to calculate the density. Eventually, this will be a new important clue to how the moon formed.

Previously, radio tracking from the Soviet Phobos 88 mission and from the spacecraft orbiting Mars in the past decades had provided the most accurate mass.

“We can be ten times more precise in our frequency shift measurements today,” says Rosenblatt.

The team’s current mass estimate for Phobos is 1.072 X 10^16 kg, or about one-billionth the mass of the Earth.

Preliminary density calculations suggest that it is just 1.85 grams per cubic centimeter. This is lower than the density of the martian surface rocks, which are 2.7-3.3 grams per cubic centimeter, but very similar to that of some asteroids.

Asteroids that share Phobos’ density are known as D-class. They are believed to be highly fractured bodies containing giant caverns because they are not solid. Instead, they are a collection of pieces held together by gravity. Scientists call them rubble piles.

Also, spectroscopic data from Mars Express and previous spacecraft show that Phobos has a similar composition to these asteroids. This suggests that Phobos, and probably its smaller sibling Deimos, are captured asteroids. However, one observation remains difficult to explain in this scenario.

Usually captured asteroids are injected into random orbits around the planet that gravitationally tie them, but Phobos orbits above Mars’ equator — a very specific case. Scientists do not yet understand how it could do this.

In another scenario, martian rocks that were blasted into space during a large meteorite impact could have made Phobos. These pieces have not fallen completely together, thus creating the rubble pile.

So the question remains, where did the original material come from — Mars’ surface or the asteroid belt? The MARSIS radar on board Mars Express also has collected data about Phobos’ subsurface. This data, together with that from the moon’s surface and surroundings gathered by the other Mars Express instruments, also will help put constraints on the origin. It’s clear though that the whole truth will only be known when samples of the moon are brought back to Earth for analysis in laboratories.

This exciting possibility might soon become reality because the Russians will attempt to do this with the Phobos-Grunt mission, to be launched next year. To land on Phobos and navigate correctly, they will need the precise knowledge of the mass as measured by the MaRS Experiment.