Key Takeaways:

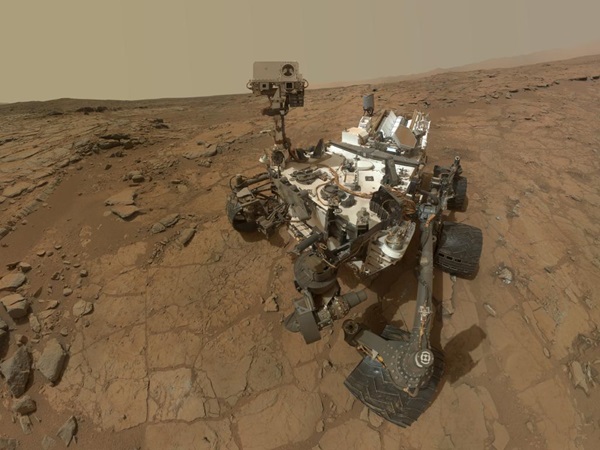

One of Curiosity’s first major findings after landing on the Red Planet in August 2012 was an ancient riverbed at its landing site. Nearby, at an area known as Yellowknife Bay, the mission met its main goal of determining whether Gale Crater ever was habitable for simple life-forms. The answer, a historic “yes,” came from two mudstone slabs that the rover sampled with its drill. Analysis of these samples revealed that the site was once a lakebed with mild water, the essential elemental ingredients for life, and a type of chemical energy source used by some microbes on Earth. If Mars had living organisms, this would have been a good home for them.

Other important findings during the first martian year include:

— Assessing natural radiation levels both during the flight to Mars and on the martian surface provides guidance for designing the protection needed for human missions to Mars.

— Measurements of heavy-versus-light variants of elements in the martian atmosphere indicate that much of Mars’ early atmosphere disappeared by processes favoring loss of lighter atoms, such as from the top of the atmosphere. Other measurements found that the atmosphere holds very little, if any, methane, a gas that can be produced biologically.

— The first determinations of the age of a rock on Mars and how long a rock has been exposed to harmful radiation provide prospects for learning when water flowed and for assessing degradation rates of organic compounds in rocks and soils.

Curiosity paused in driving this spring to drill and collect a sample from a sandstone site called Windjana. The rover currently is carrying some of the rock powder sample collected at the site for follow-up analysis.

“Windjana has more magnetite than previous samples we’ve analyzed,” said David Blake from NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California. “A key question is whether this magnetite is a component of the original basalt or resulted from later processes, such as would happen in water-soaked basaltic sediments. The answer is important to our understanding of habitability and the nature of the early Mars environment.”

Preliminary indications are that the rock contains a more diverse mix of clay minerals than was found in the mission’s only previously drilled rocks, the mudstone targets at Yellowknife Bay. Windjana also contains an unexpectedly high amount of the mineral orthoclase, a potassium-rich feldspar that is one of the most abundant minerals in Earth’s crust that had never before been definitively detected on Mars.

This finding implies that some rocks on the Gale Crater rim, from which the Windjana sandstones are thought to have been derived, may have experienced complex geological processing, such as multiple episodes of melting.

“It’s too early for conclusions, but we expect the results to help us connect what we learned at Yellowknife Bay to what we’ll learn at Mount Sharp,” said John Grotzinger, Curiosity project scientist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “Windjana is still within an area where a river flowed. We see signs of a complex history of interaction between water and rock.”

Curiosity departed Windjana in mid-May and is advancing westward. It has covered about nine-tenths of a mile (1.5 kilometers) in 23 driving days and brought the mission’s odometer tally up to 4.9 miles (7.9km).

Since wheel damage prompted a slowdown in driving late in 2013, the mission team has adjusted routes and driving methods to reduce the rate of damage.

For example, the mission team revised the planned route to future destinations on the lower slope of an area called Mount Sharp, where scientists expect geological layering will yield answers about ancient environments. Before Curiosity landed, scientists anticipated that the rover would need to reach Mount Sharp to meet the goal of determining whether the ancient environment was favorable for life. They found an answer much closer to the landing site. The findings so far have raised the bar for the work ahead. At Mount Sharp, the mission team will seek evidence not only of habitability, but also of how environments evolved and what conditions favored preservation of clues to whether life existed there.

The entry gate to the mountain is a gap in a band of dunes edging the mountain’s northern flank that is approximately 2.4 miles (3.9km) ahead of the rover’s current location. The new path will take Curiosity across sandy patches as well as rockier ground. Terrain mapping with use of imaging from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter enables the charting of safer, though longer, routes.

The team expects it will need to continually adapt to the threats posed by the terrain to the rover’s wheels but does not expect this will be a determining factor in the length of Curiosity’s operational life.

“We are getting in some long drives using what we have learned,” said Jim Erickson from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “When you’re exploring another planet, you expect surprises. The sharp embedded rocks were a bad surprise. Yellowknife Bay was a good surprise.”