Over the past century, astronomers have become aware of just how dynamic the Sun really is. One of the most dramatic manifestations of this is a coronal mass ejection (CME), where billions of tons of matter is thrown into space. If a CME reaches Earth, it creates inclement “space weather” that can disrupt communications, power grids, and the delicate systems on orbiting satellites. This potential damage means there is a keen interest in understanding exactly what triggers a CME outburst.

Now a team of researchers from University College London (UCL) has used data from the Hinode spacecraft to reveal new details of the formation of an immense magnetic structure that erupted to produce a CME December 7, 2007.

The Sun’s behavior is shaped by the presence of magnetic fields that thread through the solar atmosphere. The magnetic fields may take on different shapes from uniform arches to coherent bundles of field lines known as “flux ropes.” Understanding the exact structure of magnetic fields is a crucial part of the effort to determine how the fields evolve and the role they play in solar eruptions. In particular, flux ropes are thought to play a vital role in the CME process, having been frequently detected in interplanetary space as CMEs reach the vicinity of Earth.

“Magnetic flux ropes have been observed in interplanetary space for many years, and they are widely invoked in theoretical descriptions of how CMEs are produced,” said Lucie Green, lead researcher. “We now need observations to confirm or reject the existence of flux ropes in the solar atmosphere before an eruption takes place to see whether our theories are correct.”

The formation of the flux rope requires that significant energy is stored in the solar atmosphere. The rope is expected to remain stable while the solar magnetic field in the vicinity holds it down.

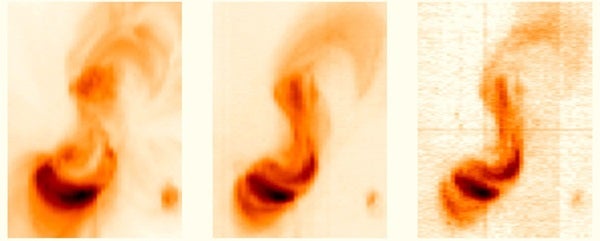

But at some point the structure becomes unstable and erupts to produce a CME. Using data from the Hinode spacecraft, Green showed that a flux rope formed in the solar atmosphere over the 2.5 days that preceded the December 2007 event. Evidence for the flux rope takes the form of S-shaped structures clearly seen by one of the Hinode instruments, the Extreme-Ultraviolet Imaging Telescope.

The key point to understanding and predicting the formation of CMEs is to know when the flux rope becomes unstable. Combining the observations of the S-shaped structure with information on how the magnetic field in the region evolves has enabled Green to work out when this happened. The work shows that more than 30 percent of the magnetic field of the region had been transformed into the flux rope before it became unstable, 3 times what had been suggested in theory.

Green sees a better understanding of magnetic flux ropes and their role in emissions from the Sun and other stars as one of the most pressing questions — not just for solar physics, but astronomy as a whole.

“Flux ropes are thought to play a vital role in the evolution of the magnetic field of the Sun,” said Green. “However, the physics of flux ropes is applied across the universe. For example, a solar physics model of flux rope ejection was recently used to explain the jets driven by the accretion disks around the supermassive black holes found in the center of galaxies.”