Key Takeaways:

- The "cooling-flow problem" in galaxy clusters involves a discrepancy between the predicted rapid cooling of hot gas leading to intense star formation in central galaxies and the observed lack thereof in most cases. This is hypothesized to be due to energy injection from supermassive black hole jets.

- The Phoenix Cluster presents an exception, exhibiting unusually high star formation rates (500 solar masses per year) despite possessing a massive (10 billion solar masses) central black hole and strong jets. This cluster is also exceptionally large and luminous.

- Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers detected neon VI emission, mapping intermediate-temperature gas (around 300,000°C) within the Phoenix Cluster. This gas bridges the hot and cold gas phases, providing evidence for a cooling flow as the mechanism driving the observed starburst.

- While this observation supports the cooling flow model, the unique characteristics of the Phoenix Cluster raise questions about the frequency and duration of such events and the generality of the cooling-flow problem's resolution. Further studies of more typical clusters are planned.

Scientists have a good idea how stars should form in the central galaxies of rich clusters. The hot gas surrounding a cluster’s dominant innermost galaxy cools rapidly, sparking furious star formation. The problem: No one had found evidence for this cooling gas, and most central galaxies don’t create many stars.

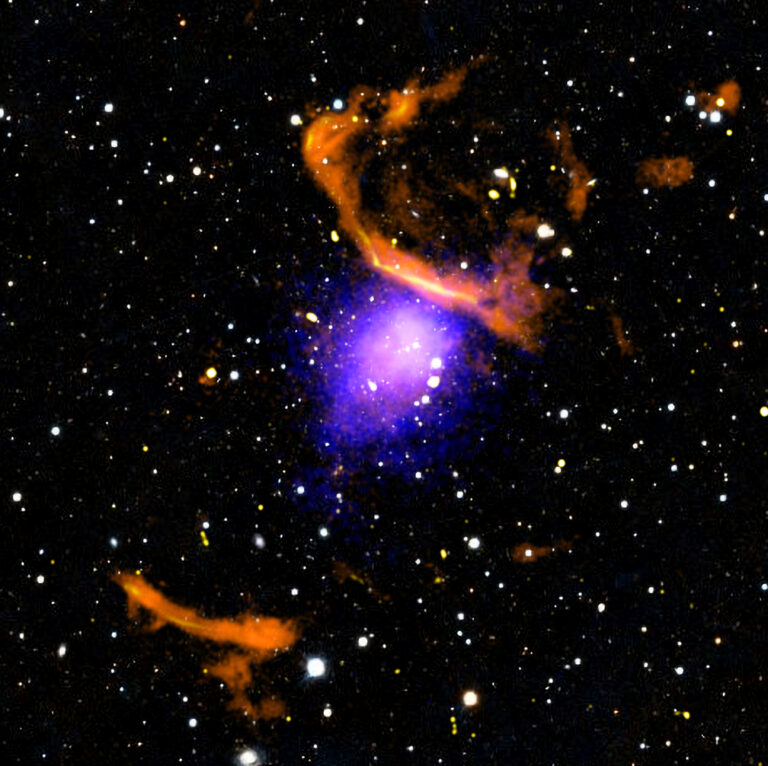

Astronomers suspect the solution to this so-called cooling-flow problem lies with the supermassive black hole that lurks at the heart of each central galaxy. As matter falls toward the black hole, it forms an accretion disk where temperatures soar to millions of degrees. The disks can amplify existing magnetic fields and ignite twin jets of high-speed particles that burst out perpendicular to the disk in opposite directions. The particles inject energy into the galaxy’s surroundings, preventing the gas from cooling.

An exception in Phoenix

It’s no wonder astronomers wanted to use the James Webb Space Telescope’s (JWST) unique capabilities to explore the Phoenix Cluster. The cluster’s central galaxy turns at least 500 solar masses of gas into stars each year. Few other such galaxies convert more than 10 solar masses per year. And this happens despite the galaxy having a supermassive black hole that weighs roughly 10 billion solar masses and generates strong jets.

This isn’t the only reason the cluster and galaxy stand out. The Phoenix Cluster ranks among the most massive known, holding some 2 trillion solar masses. It also has the highest X-ray luminosity of any cluster. Meanwhile, its central galaxy places among the largest ever identified, with a diameter estimated at more than 500,000 light-years.

It might surprise you that astronomers didn’t discover this exceptional cluster until 2010. It turned up in a radio survey made with the 10-meter South Pole Telescope in Antarctica. The cluster’s shyness stems from its enormous distance of 5.8 billion light-years.

A neon sign

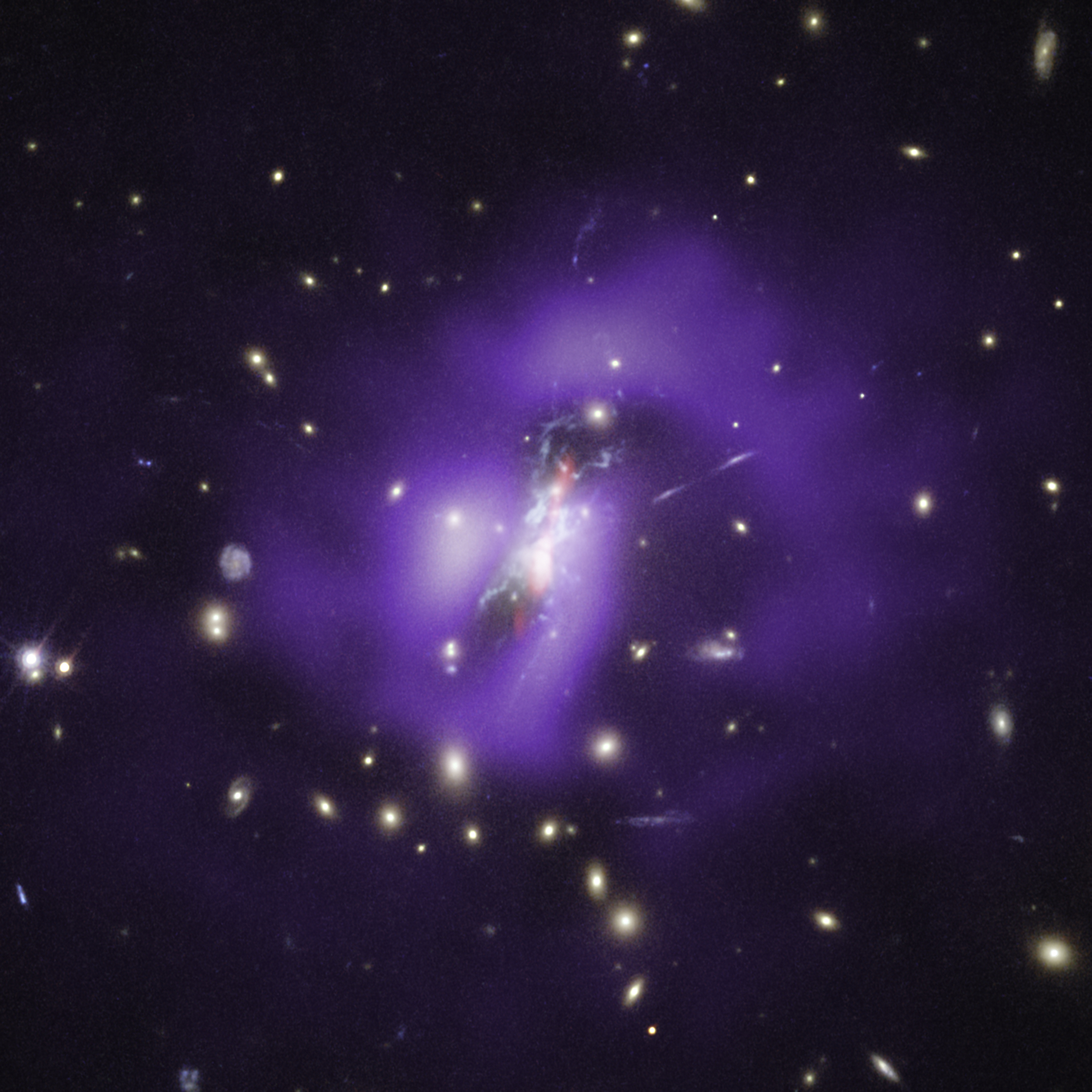

With JWST, astronomers sought a missing link in the Phoenix Cluster. Scientists earlier had observed superhot gas glowing at 18,000,000 degrees Fahrenheit (10,000,000 degrees Celsius) and much colder gas at 18,000 F (10,000 C). Any cooling flow would show up at an intermediate temperature beyond the reach of any other telescope.

“Previous studies only measured gas at the extreme cold and hot ends of the temperature distribution throughout the center of the cluster. It was not possible to detect the warm gas that we were looking for,” said MIT astronomer Michael McDonald, principal investigator of the JWST program, in a press release. “With Webb, we could do this for the first time.”

The researchers used JWST’s Medium-Resolution Spectrometer to map emissions from neon VI, neon atoms that have lost five electrons. It tracks the cooling gas at temperatures around 540,000 F (300,000 C). “In the mid-infrared wavelengths detected by Webb, the neon VI signature was absolutely booming,” said MIT graduate student Michael Reefe, lead author on the team’s paper published in the Feb. 5 issue of Nature. Most importantly, this warm gas lies between the cavities that trace the hot gas and the cold gas where stars are forming.

The cooling flow matches what astronomers once expected to find in clusters but had not seen before. This could mean such flows represent brief episodes, lasting only 10 million years or so, and we see the Phoenix Cluster at this special time. Even such a short lifetime wouldn’t explain the lack of intense star formation in other clusters, however, raising the possibility that the one in Phoenix is unique. The scientists now plan to study more typical clusters to better understand these extreme environments.